openSUSE Leap 42.1

System Analysis and Tuning Guide

An administrator's guide for problem detection, resolution and optimization. Find how to inspect and optimize your system by means of monitoring tools and how to efficiently manage resources. Also contains an overview of common problems and solutions and of additional help and documentation resources.

- About This Guide

- I Basics

- II System Monitoring

- III Kernel Monitoring

- IV Resource Management

- V Kernel Tuning

- VI Handling System Dumps

- VII Synchronized Clocks with Precision Time Protocol

- A GNU Licenses

- 2.1

vmstatOutput on a Lightly Used Machine - 2.2

vmstatOutput on a Heavily Used Machine (CPU bound) - 3.1 Example for

/etc/logrotate.conf - 4.1 Simple SystemTap Script

- 4.2 Probe with Timer Event

- 4.3

printfFunction with Format Specifiers - 4.4 Using Global Variables

- 4.5 Monitoring Incoming TCP Connections with

tcp_connections.stp - 11.1 Example Output of

cpupower frequency-info - 11.2 Example Output of

cpupower idle-info - 11.3 Example

cpupower monitorOutput - 11.4 Example powerTOP Output

- 12.1 Increasing individual thread throughput using

CFQ - 18.1 Slave clock using software time stamping

- 18.2 Slave clock using hardware time stamping

- 18.3 Master clock using hardware time stamping

- 18.4 Master clock using software time stamping (not generally recommended)

Copyright © 2006–2018 SUSE LLC and contributors. All rights reserved.

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or (at your option) version 1.3; with the Invariant Section being this copyright notice and license. A copy of the license version 1.2 is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”.

For SUSE trademarks, see http://www.suse.com/company/legal/. All other third party trademarks are the property of their respective owners. A trademark symbol (®, ™ etc.) denotes a SUSE or Novell trademark; an asterisk (*) denotes a third party trademark.

All information found in this book has been compiled with utmost attention to detail. However, this does not guarantee complete accuracy. Neither SUSE LLC, its affiliates, the authors nor the translators shall be held liable for possible errors or the consequences thereof.

About This Guide #

openSUSE Leap is used for a broad range of usage scenarios in enterprise and scientific data centers. SUSE has ensured openSUSE Leap is set up in a way that it accommodates different operation purposes with optimal performance. However, openSUSE Leap must meet very different demands when employed on a number crunching server compared to a file server, for example.

It is not possible to ship a distribution that is optimized for all workloads. Different workloads vary substantially in some aspects. Most important among those are I/O access patterns, memory access patterns, and process scheduling. A behavior that perfectly suits a certain workload might reduce performance of another workload. For example, I/O-intensive tasks, such as handling database requests, usually have completely different requirements than CPU-intensive tasks, such as video encoding. The versatility of Linux makes it possible to configure your system in a way that it brings out the best in each usage scenario.

This manual introduces you to means to monitor and analyze your system. It describes methods to manage system resources and to tune your system. This guide does not offer recipes for special scenarios, because each server has got its own different demands. It rather enables you to thoroughly analyze your servers and make the most out of them.

- General Notes on System Tuning

Tuning a system requires a carefully planned proceeding. Learn which steps are necessary to successfully improve your system.

- Part II, “System Monitoring”

Linux offers a large variety of tools to monitor almost every aspect of the system. Learn how to use these utilities and how to read and analyze the system log files.

- Part III, “Kernel Monitoring”

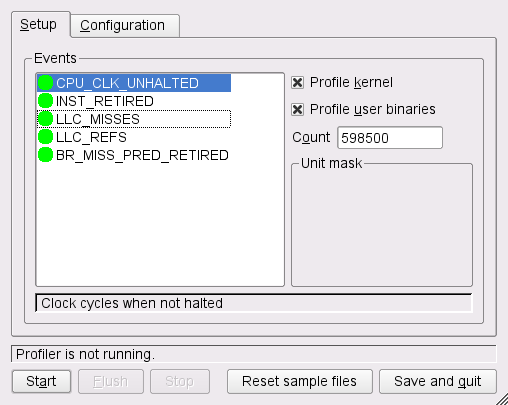

The Linux kernel itself offers means to examine every nut, bolt and screw of the system. This part introduces you to SystemTap, a scripting language for writing kernel modules that can be used to analyze and filter data. Collect debugging information and find bottlenecks by using kernel probes. Last, monitor applications with the help of Oprofile.

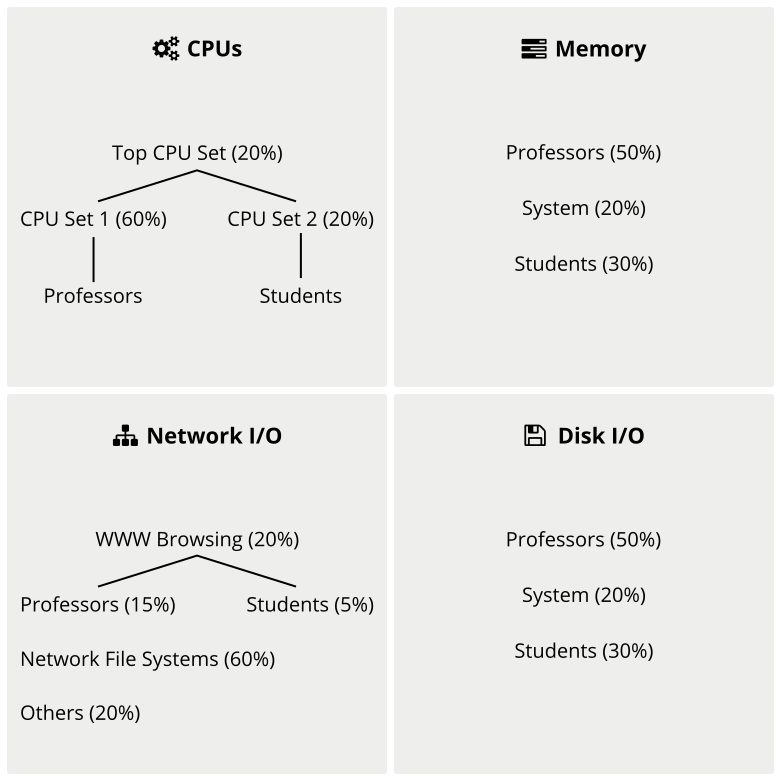

- Part IV, “Resource Management”

Learn how to set up a tailor-made system fitting exactly the server's need. Get to know how to use power management while at the same time keeping the performance of a system at a level that matches the current requirements.

- Part V, “Kernel Tuning”

The Linux kernel can be optimized either by using sysctl or via the

/procfile system. This part covers tuning the I/O performance and optimizing the way how Linux schedules processes. It also describes basic principles of memory management and shows how memory management could be fine-tuned to suit needs of specific applications and usage patterns. Furthermore, it describes how to optimize network performance.- Part VI, “Handling System Dumps”

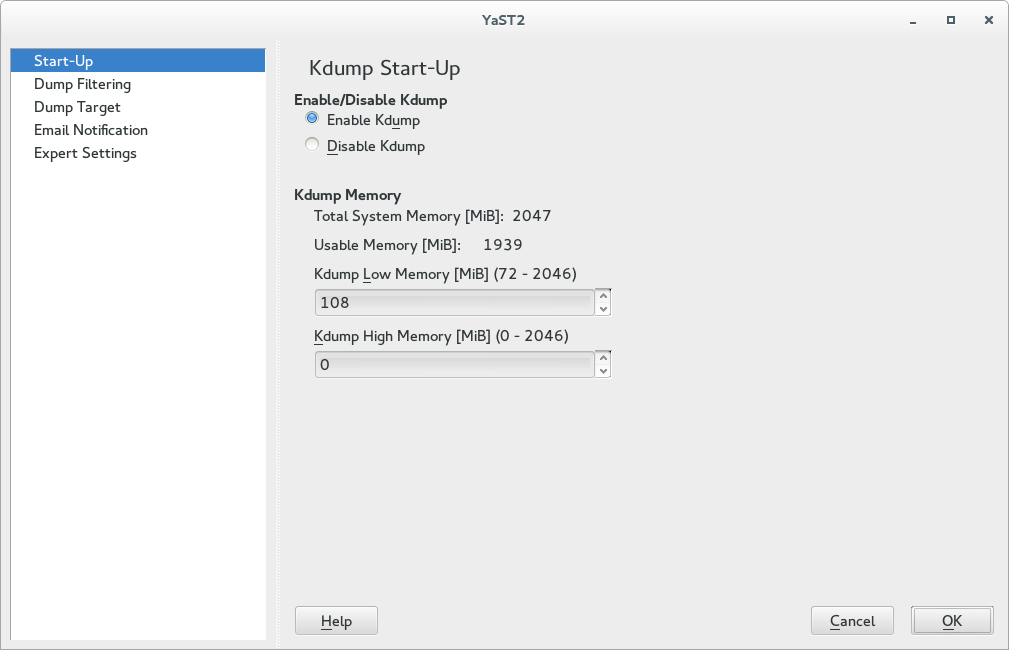

This part enables you to analyze and handle application or system crashes. It introduces tracing tools such as strace or ltrace and describes how to handle system crashes using Kexec and Kdump.

Tip: Getting the SUSE Linux Enterprise SDK

The SDK is a module for SUSE Linux Enterprise and is available via an online channel from

the SUSE Customer Center. Alternatively, go to http://download.suse.com/, search for SUSE Linux Enterprise

Software Development Kit and download it from there.

Refer to Book “Start-Up”, Chapter 10 “Installing Add-On Products” for details.

Many chapters in this manual contain links to additional documentation resources. This includes additional documentation that is available on the system and documentation available on the Internet.

For an overview of the documentation available for your product and the latest documentation updates, refer to http://www.suse.com/doc or to the following section:

1 Available Documentation #

We provide HTML and PDF versions of our books in different languages. The following manuals for users and administrators are available for this product:

- Book “Start-Up”

This manual will see you through your initial contact with openSUSE® Leap. Check out the various parts of this manual to learn how to install, use and enjoy your system.

- Book “Reference”

Covers system administration tasks like maintaining, monitoring and customizing an initially installed system.

- Book “Virtualization Guide”

Describes virtualization technology in general, and introduces libvirt—the unified interface to virtualization—and detailed information on specific hypervisors.

- Book “AutoYaST”

AutoYaST is a system for installing one or more openSUSE Leap systems automatically and without user intervention, using an AutoYaST profile that contains installation and configuration data. The manual guides you through the basic steps of auto-installation: preparation, installation, and configuration.

- Book “Security Guide”

Introduces basic concepts of system security, covering both local and network security aspects. Shows how to use the product inherent security software like AppArmor or the auditing system that reliably collects information about any security-relevant events.

- System Analysis and Tuning Guide

An administrator's guide for problem detection, resolution and optimization. Find how to inspect and optimize your system by means of monitoring tools and how to efficiently manage resources. Also contains an overview of common problems and solutions and of additional help and documentation resources.

- Book “GNOME User Guide”

Introduces the GNOME desktop of openSUSE Leap. It guides you through using and configuring the desktop and helps you perform key tasks. It is intended mainly for end users who want to make efficient use of GNOME as their default desktop.

Find HTML versions of most product manuals in your installed system under

/usr/share/doc/manual or in the help centers of your

desktop. Find the latest documentation updates at http://doc.opensuse.org/ where you

can download PDF or HTML versions of the manuals for your product.

2 Feedback #

Several feedback channels are available:

- Bugs and Enhancement Requests

For services and support options available for your product, refer to http://www.suse.com/support/.

To report bugs for a product component, go to https://scc.suse.com/support/requests, log in, and click .

- User Comments

We want to hear your comments about and suggestions for this manual and the other documentation included with this product. Use the User Comments feature at the bottom of each page in the online documentation or go to http://www.suse.com/doc/feedback.html and enter your comments there.

For feedback on the documentation of this product, you can also send a mail to

doc-team@suse.de. Make sure to include the document title, the product version and the publication date of the documentation. To report errors or suggest enhancements, provide a concise description of the problem and refer to the respective section number and page (or URL).

3 Documentation Conventions #

The following typographical conventions are used in this manual:

/etc/passwd: directory names and file namesplaceholder: replace placeholder with the actual value

PATH: the environment variable PATHls,--help: commands, options, and parametersuser: users or groupsAlt, Alt–F1: a key to press or a key combination; keys are shown in uppercase as on a keyboard

, › : menu items, buttons

Dancing Penguins (Chapter Penguins, ↑Another Manual): This is a reference to a chapter in another manual.

Part I Basics #

- 1 General Notes on System Tuning

This manual discusses how to find the reasons for performance problems and provides means to solve these problems. Before you start tuning your system, you should make sure you have ruled out common problems and have found the cause for the problem. You should also have a detailed plan on how to tune the system, because applying random tuning tips often will not help and could make things worse.

1 General Notes on System Tuning #

Abstract#

This manual discusses how to find the reasons for performance problems and provides means to solve these problems. Before you start tuning your system, you should make sure you have ruled out common problems and have found the cause for the problem. You should also have a detailed plan on how to tune the system, because applying random tuning tips often will not help and could make things worse.

Procedure 1.1: General Approach When Tuning a System #

Specify the problem that needs to be solved.

In case the degradation is new, identify any recent changes to the system.

Identify why the issue is considered a performance problem.

Specify a metric that can be used to analyze performance. This metric could for example be latency, throughput, the maximum number of simultaneously logged-in users, or the maximum number of active users.

Measure current performance using the metric from the previous step.

Identify the subsystem(s) where the application is spending the most time.

Monitor the system and/or the application.

Analyze the data, categorize where time is being spent.

Tune the subsystem identified in the previous step.

Remeasure the current performance without monitoring using the same metric as before.

If performance is still not acceptable, start over with Step 3.

1.1 Be Sure What Problem to Solve #

Before starting to tuning a system, try to describe the problem as exactly as possible. A statement like “The system is slow!” is not a helpful problem description. For example, it could make a difference whether the system speed needs to be improved in general or only at peak times.

Furthermore, make sure you can apply a measurement to your problem, otherwise you will not be able to verify if the tuning was a success or not. You should always be able to compare “before” and “after”. Which metrics to use depends on the scenario or application you are looking into. Relevant Web server metrics, for example, could be expressed in terms of

- Latency

The time to deliver a page throughput, measured in pages per second or megabytes per second

- Active Users

The maximum number of users that can be downloading pages while still receiving pages within an acceptable latency

1.2 Rule Out Common Problems #

A performance problem often is caused by network or hardware problems, bugs, or configuration issues. Make sure to rule out problems such as the ones listed below before attempting to tune your system:

Check the output of the

systemdjournal (see Book “Reference”, Chapter 11 “journalctl: Query thesystemdJournal”) for unusual entries.Check (using

toporps) whether a certain process misbehaves by eating up unusual amounts of CPU time or memory.Check for network problems by inspecting

/proc/net/dev.In case of I/O problems with physical disks, make sure it is not caused by hardware problems (check the disk with the

smartmontools) or by a full disk.Ensure that background jobs are scheduled to be carried out in times the server load is low. Those jobs should also run with low priority (set via

nice).If the machine runs several services using the same resources, consider moving services to another server.

Last, make sure your software is up-to-date.

1.3 Finding the Bottleneck #

Finding the bottleneck very often is the hardest part when tuning a system. openSUSE Leap offers many tools to help you with this task. See Part II, “System Monitoring” for detailed information on general system monitoring applications and log file analysis. If the problem requires a long-time in-depth analysis, the Linux kernel offers means to perform such analysis. See Part III, “Kernel Monitoring” for coverage.

Once you have collected the data, it needs to be analyzed. First, inspect if the server's hardware (memory, CPU, bus) and its I/O capacities (disk, network) are sufficient. If these basic conditions are met, the system might benefit from tuning.

1.4 Step-by-step Tuning #

Make sure to carefully plan the tuning itself. It is of vital importance to only do one step at a time. Only by doing so you will be able to measure if the change provided an improvement or even had a negative impact. Each tuning activity should be measured over a sufficient time period to ensure you can do an analysis based on significant data. If you cannot measure a positive effect, do not make the change permanent. Chances are, that it might have a negative effect in the future.

Part II System Monitoring #

- 2 System Monitoring Utilities

There are number of programs, tools, and utilities which you can use to examine the status of your system. This chapter introduces some and describes their most important and frequently used parameters.

- 3 Analyzing and Managing System Log Files

System log file analysis is one of the most important tasks when analyzing the system. In fact, looking at the system log files should be the first thing to do when maintaining or troubleshooting a system. openSUSE Leap automatically logs almost everything that happens on the system in detail. Since…

For each of the described commands, examples of the relevant outputs are

presented. In the examples, the first line is the command itself (after

the tux > or root #). Omissions are indicated with

square brackets ([...]) and long lines are wrapped

where necessary. Line breaks for long lines are indicated by a backslash

(\).

tux > command -x -y

output line 1

output line 2

output line 3 is annoyingly long, so long that \

we need to break it

output line 4

[...]

output line 98

output line 99

The descriptions have been kept short so that we can include as many

utilities as possible. Further information for all the commands can be

found in the manual pages. Most of the commands also understand the

parameter --help, which produces a brief list of possible

parameters.

2.1 Multi-Purpose Tools #

While most Linux system monitoring tools monitor only a single aspect of the system, there are a few tools with a broader scope. To get an overview and find out which part of the system to examine further, use these tools first.

2.1.1 vmstat #

vmstat collects information about processes, memory, I/O, interrupts and CPU. If called without a sampling rate, it displays average values since the last reboot. When called with a sampling rate, it displays actual samples:

Example 2.1: vmstat Output on a Lightly Used Machine #

tux > vmstat 2

procs -----------memory---------- ---swap-- -----io---- -system-- ------cpu-----

r b swpd free buff cache si so bi bo in cs us sy id wa st

1 0 44264 81520 424 935736 0 0 12 25 27 34 1 0 98 0 0

0 0 44264 81552 424 935736 0 0 0 0 38 25 0 0 100 0 0

0 0 44264 81520 424 935732 0 0 0 0 23 15 0 0 100 0 0

0 0 44264 81520 424 935732 0 0 0 0 36 24 0 0 100 0 0

0 0 44264 81552 424 935732 0 0 0 0 51 38 0 0 100 0 0Example 2.2: vmstat Output on a Heavily Used Machine (CPU bound) #

tux > vmstat 2

procs -----------memory----------- ---swap-- -----io---- -system-- -----cpu------

r b swpd free buff cache si so bi bo in cs us sy id wa st

32 1 26236 459640 110240 6312648 0 0 9944 2 4552 6597 95 5 0 0 0

23 1 26236 396728 110336 6136224 0 0 9588 0 4468 6273 94 6 0 0 0

35 0 26236 554920 110508 6166508 0 0 7684 27992 4474 4700 95 5 0 0 0

28 0 26236 518184 110516 6039996 0 0 10830 4 4446 4670 94 6 0 0 0

21 5 26236 716468 110684 6074872 0 0 8734 20534 4512 4061 96 4 0 0 0Tip: First Line of Output

The first line of the vmstat output always displays average values since the last reboot.

The columns show the following:

Shows the number of processes in the run queue. These processes are waiting for a free CPU slot to be executed. If the number of processes in this column is constantly higher than the number of CPUs available, this is an indication of insufficient CPU power.

Shows the number of processes waiting for a resource other than a CPU. A high number in this column may indicate an I/O problem (network or disk).

The amount of swap space (KB) currently used.

The amount of unused memory (KB).

Recently unused memory that can be reclaimed. This column is only visible when calling

vmstatwith the parameter-a(recommended).Recently used memory that normally does not get reclaimed. This column is only visible when calling

vmstatwith the parameter-a(recommended).File buffer cache (KB) in RAM. This column is not visible when calling

vmstatwith the parameter-a(recommended).Page cache (KB) in RAM. This column is not visible when calling

vmstatwith the parameter-a(recommended).Amount of data (KB) that is moved from swap to RAM (

si) or from RAM to swap (so) per second. Highsovalues over a long period of time may indicate that an application is leaking memory and the leaked memory is being swapped out. Highsivalues over a long period of time could mean that an application that was inactive for a very long time is now active again. Combined highsiandsovalues for prolonged periods of time are evidence of swap thrashing and may indicate that more RAM needs to be installed in the system because there is not enough memory to hold the working set size.Number of blocks per second received from a block device (for example, a disk read). Note that swapping also impacts the values shown here.

Number of blocks per second sent to a block device (for example, a disk write). Note that swapping also impacts the values shown here.

Interrupts per second. A high value may indicate a high I/O level (network and/or disk), but could also be triggered for other reasons such as inter-processor interrupts triggered by another activity. Make sure to also check

/proc/interruptsto identify the source of interrupts.Number of context switches per second. This is the number of times that the kernel replaces executable code of one program in memory with that of another program.

Percentage of CPU usage from user processes.

Percentage of CPU usage from system processes.

Percentage of CPU time spent idling. If this value is zero over a longer period of time, your CPU(s) are working to full capacity. This is not necessarily a bad sign—rather refer to the values in columns and to determine if your machine is equipped with sufficient CPU power.

If "wa" time is non-zero, it indicates throughput lost because of waiting for I/O. This may be inevitable, for example, if a file is being read for the first time, background writeback cannot keep up, and so on. It can also be an indicator for a hardware bottleneck (network or hard disk). Lastly, it can indicate a potential for tuning the virtual memory manager (refer to Chapter 14, Tuning the Memory Management Subsystem).

Percentage of CPU time used by virtual machines.

See vmstat --help for more options.

2.1.2 System Activity Information: sar #

sar can generate extensive reports on almost all

important system activities, among them CPU, memory, IRQ usage, IO, or

networking. It can also generate reports on the fly.

sar gathers all their data from the

/proc file system.

Note: sysstat Package

sar is a part of the

sysstat package. You need to install the

package either with YaST, or with zypper in

sysstat.

2.1.2.1 Generating reports with sar #

To generate reports on the fly, call sar with an

interval (seconds) and a count. To generate reports from files specify

a file name with the option -f instead of interval and

count. If file name, interval and count are not specified,

sar attempts to generate a report from

/var/log/sa/saDD, where

DD stands for the current day. This is the

default location to where sadc writes its data.

Query multiple files with multiple -f options.

sar 2 10 # on-the-fly report, 10 times every 2 seconds sar -f ~/reports/sar_2014_07_17 # queries file sar_2014_07_17 sar # queries file from today in /var/log/sa/ cd /var/log/sa &&\ sar -f sa01 -f sa02 # queries files /var/log/sa/0[12]

Find examples for useful sar calls and their

interpretation below. For detailed information on the meaning of each

column, refer to the man (1) of

sar. Also refer to the man page for more options and

reports—sar offers plenty of them.

2.1.2.1.1 CPU Usage Report: sar #

When called with no options, sar shows a basic

report about CPU usage. On multi-processor machines, results for all

CPUs are summarized. Use the option -P ALL to also

see statistics for individual CPUs.

root # sar 10 5

Linux 3.12.24-7-default (jupiter) 07/17/14 _x86_64_ (2 CPU)

17:51:29 CPU %user %nice %system %iowait %steal %idle

17:51:39 all 57,93 0,00 9,58 1,01 0,00 31,47

17:51:49 all 32,71 0,00 3,79 0,05 0,00 63,45

17:51:59 all 47,23 0,00 3,66 0,00 0,00 49,11

17:52:09 all 53,33 0,00 4,88 0,05 0,00 41,74

17:52:19 all 56,98 0,00 5,65 0,10 0,00 37,27

Average: all 49,62 0,00 5,51 0,24 0,00 44,62displays the percentage of time that the CPU was idle while waiting for an I/O request. If this value is significantly higher than zero over a longer time, there is a bottleneck in the I/O system (network or hard disk). If the value is zero over a longer period of time, your CPU is working at capacity.

2.1.2.1.2 Memory Usage Report: sar -r #

Generate an overall picture of the system memory (RAM) by using the

option -r:

root # sar -r 10 5

Linux 3.12.24-7-default (jupiter) 07/17/14 _x86_64_ (2 CPU)

17:55:27 kbmemfree kbmemused %memused kbbuffers kbcached kbcommit %commit kbactive kbinact kbdirty

17:55:37 104232 1834624 94.62 20 627340 2677656 66.24 802052 828024 1744

17:55:47 98584 1840272 94.92 20 624536 2693936 66.65 808872 826932 2012

17:55:57 87088 1851768 95.51 20 605288 2706392 66.95 827260 821304 1588

17:56:07 86268 1852588 95.55 20 599240 2739224 67.77 829764 820888 3036

17:56:17 104260 1834596 94.62 20 599864 2730688 67.56 811284 821584 3164

Average: 96086 1842770 95.04 20 611254 2709579 67.03 815846 823746 2309The columns and show an approximation of the maximum amount of memory (RAM and swap) that the current workload could need. While displays the absolute number in kilobytes, displays a percentage.

2.1.2.1.3 Paging Statistics Report: sar -B #

Use the option -B to display the kernel paging

statistics.

root # sar -B 10 5

Linux 3.12.24-7-default (jupiter) 07/17/14 _x86_64_ (2 CPU)

18:23:01 pgpgin/s pgpgout/s fault/s majflt/s pgfree/s pgscank/s pgscand/s pgsteal/s %vmeff

18:23:11 366.80 11.60 542.50 1.10 4354.80 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

18:23:21 0.00 333.30 1522.40 0.00 18132.40 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

18:23:31 47.20 127.40 1048.30 0.10 11887.30 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

18:23:41 46.40 2.50 336.10 0.10 7945.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

18:23:51 0.00 583.70 2037.20 0.00 17731.90 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

Average: 92.08 211.70 1097.30 0.26 12010.28 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00The (major faults per second) column shows how many pages are loaded from disk into memory. The source of the faults may be file accesses or faults. There are times when a large number of major faults are normal such as during application start-up time. If major faults are experienced for the entire lifetime of the application it may be an indication that there is insufficient main memory, particularly if combined with large amounts of direct scanning (pgscand/s).

The column shows the number of pages scanned () in relation to the ones being reused from the main memory cache or the swap cache (). It is a measurement of the efficiency of page reclaim. Healthy values are either near 100 (every inactive page swapped out is being reused) or 0 (no pages have been scanned). The value should not drop below 30.

2.1.2.1.4 Block Device Statistics Report: sar -d #

Use the option -d to display the block device (hard

disk, optical drive, USB storage device, etc.). Make sure to use the

additional option -p (pretty-print) to make the

column readable.

root # sar -d -p 10 5

Linux 3.12.24-7-default (jupiter) 07/17/14 _x86_64_ (2 CPU)

18:46:09 DEV tps rd_sec/s wr_sec/s avgrq-sz avgqu-sz await svctm %util

18:46:19 sda 1.70 33.60 0.00 19.76 0.00 0.47 0.47 0.08

18:46:19 sr0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

18:46:19 DEV tps rd_sec/s wr_sec/s avgrq-sz avgqu-sz await svctm %util

18:46:29 sda 8.60 114.40 518.10 73.55 0.06 7.12 0.93 0.80

18:46:29 sr0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

18:46:29 DEV tps rd_sec/s wr_sec/s avgrq-sz avgqu-sz await svctm %util

18:46:39 sda 40.50 3800.80 454.90 105.08 0.36 8.86 0.69 2.80

18:46:39 sr0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

18:46:39 DEV tps rd_sec/s wr_sec/s avgrq-sz avgqu-sz await svctm %util

18:46:49 sda 1.40 0.00 204.90 146.36 0.00 0.29 0.29 0.04

18:46:49 sr0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

18:46:49 DEV tps rd_sec/s wr_sec/s avgrq-sz avgqu-sz await svctm %util

18:46:59 sda 3.30 0.00 503.80 152.67 0.03 8.12 1.70 0.56

18:46:59 sr0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

Average: DEV tps rd_sec/s wr_sec/s avgrq-sz avgqu-sz await svctm %util

Average: sda 11.10 789.76 336.34 101.45 0.09 8.07 0.77 0.86

Average: sr0 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00Compare the values for , , and of all disks. Constantly high values in the and columns could be an indication that the amount of free space on the disk is insufficient.

If the machine uses multiple disks, then it is best if I/O is interleaved evenly between disks of equal speed and capacity. It will be necessary to take into account whether the storage has multiple tiers. Furthermore, if there are multiple paths to storage then consider what the link saturation will be when balancing how storage is used.

2.1.2.1.5 Network Statistics Reports: sar -n KEYWORD #

The option -n lets you generate multiple network

related reports. Specify one of the following keywords along with the

-n:

DEV: Generates a statistic report for all network devices

EDEV: Generates an error statistics report for all network devices

NFS: Generates a statistic report for an NFS client

NFSD: Generates a statistic report for an NFS server

SOCK: Generates a statistic report on sockets

ALL: Generates all network statistic reports

2.1.2.2 Visualizing sar Data #

sar reports are not always easy to parse for humans.

kSar, a Java application visualizing your sar data,

creates easy-to-read graphs. It can even generate PDF reports. kSar

takes data generated on the fly and past data from a file. kSar

is licensed under the BSD license and is available from

https://sourceforge.net/projects/ksar/.

2.2 System Information #

2.2.1 Device Load Information: iostat #

To monitor the system device load, use iostat. It

generates reports that can be useful for better balancing the load

between physical disks attached to your system.

To be able to use iostat, install the package

sysstat.

The first iostat report shows statistics collected

since the system was booted. Subsequent reports cover the time since the

previous report.

tux > iostat

Linux 3.12.24-7-default (jupiter) 29/07/14 _x86_64_ (4 CPU)

avg-cpu: %user %nice %system %iowait %steal %idle

17.68 4.49 4.24 0.29 0.00 73.31

Device: tps kB_read/s kB_wrtn/s kB_read kB_wrtn

sdb 2.02 36.74 45.73 3544894 4412392

sda 1.05 5.12 13.47 493753 1300276

sdc 0.02 0.14 0.00 13641 37

Invoking iostat in this way will help you find out

whether throughput is different from your expectation, but not why.

Such questions can be better answered by an extended report which can be

generated by invoking iostat -x.

Extended reports additionally include, for example, information on average

queue sizes and average wait times.

Find definitions for each of the displayed column titles in the

man page of iostat (man 1 iostat).

You can also specify that a certain device should be monitored at specified

intervals.

For example, to generate five reports at three-second intervals for the

device sda, use:

tux >iostat-p sda 3 5

To show statistics of network file systems (NFS), there are two similar utilities:

nfsiostat-sysstatis included with the package sysstat.nfsiostatis included with the package nfs-client. The option-xshows extended statistics information.

2.2.2 Processor Activity Monitoring: mpstat #

The utility mpstat examines activities of each

available processor. If your system has one processor only, the global

average statistics will be reported.

The timing arguments work the same way as with the

iostat command. Entering mpstat 2

5 prints five reports for all processors in two-second

intervals.

root # mpstat 2 5

Linux 3.12.24-7-default (jupiter) 07/18/14 _x86_64_ (2 CPU)

13:51:10 CPU %usr %nice %sys %iowait %irq %soft %steal %guest %gnice %idle

13:51:12 all 8,27 0,00 0,50 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 91,23

13:51:14 all 46,62 0,00 3,01 0,00 0,00 0,25 0,00 0,00 0,00 50,13

13:51:16 all 54,71 0,00 3,82 0,00 0,00 0,51 0,00 0,00 0,00 40,97

13:51:18 all 78,77 0,00 5,12 0,00 0,00 0,77 0,00 0,00 0,00 15,35

13:51:20 all 51,65 0,00 4,30 0,00 0,00 0,51 0,00 0,00 0,00 43,54

Average: all 47,85 0,00 3,34 0,00 0,00 0,40 0,00 0,00 0,00 48,412.2.3 Task Monitoring: pidstat #

If you need to see what load a particular task applies to your system,

use pidstat command. It prints activity of every

selected task or all tasks managed by Linux kernel if no task is

specified. You can also set the number of reports to be displayed and

the time interval between them.

For example, pidstat -C firefox 2 3

prints the load statistic for tasks whose command name includes the

string “firefox”. There will be three reports printed at

two second intervals.

root # pidstat -C firefox 2 3

Linux 3.12.24-7-default (jupiter) 07/18/14 _x86_64_ (2 CPU)

14:09:11 UID PID %usr %system %guest %CPU CPU Command

14:09:13 1000 387 22,77 0,99 0,00 23,76 1 firefox

14:09:13 UID PID %usr %system %guest %CPU CPU Command

14:09:15 1000 387 46,50 3,00 0,00 49,50 1 firefox

14:09:15 UID PID %usr %system %guest %CPU CPU Command

14:09:17 1000 387 60,50 7,00 0,00 67,50 1 firefox

Average: UID PID %usr %system %guest %CPU CPU Command

Average: 1000 387 43,19 3,65 0,00 46,84 - firefox2.2.4 Kernel Ring Buffer: dmesg #

The Linux kernel keeps certain messages in a ring buffer. To view these

messages, enter the command dmesg -T.

Older events are logged in the systemd journal. See

Book “Reference”, Chapter 11 “journalctl: Query the systemd Journal” for more information on the journal.

2.2.5 List of Open Files: lsof #

To view a list of all the files open for the process with process ID

PID, use -p. For example, to

view all the files used by the current shell, enter:

root # lsof -p $$

COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME

bash 8842 root cwd DIR 0,32 222 6772 /root

bash 8842 root rtd DIR 0,32 166 256 /

bash 8842 root txt REG 0,32 656584 31066 /bin/bash

bash 8842 root mem REG 0,32 1978832 22993 /lib64/libc-2.19.so

[...]

bash 8842 root 2u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

bash 8842 root 255u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

The special shell variable $$, whose value is the

process ID of the shell, has been used.

When used with -i, lsof lists

currently open Internet files as well:

root # lsof -i

COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME

wickedd-d 917 root 8u IPv4 16627 0t0 UDP *:bootpc

wickedd-d 918 root 8u IPv6 20752 0t0 UDP [fe80::5054:ff:fe72:5ead]:dhcpv6-client

sshd 3152 root 3u IPv4 18618 0t0 TCP *:ssh (LISTEN)

sshd 3152 root 4u IPv6 18620 0t0 TCP *:ssh (LISTEN)

master 4746 root 13u IPv4 20588 0t0 TCP localhost:smtp (LISTEN)

master 4746 root 14u IPv6 20589 0t0 TCP localhost:smtp (LISTEN)

sshd 8837 root 5u IPv4 293709 0t0 TCP jupiter.suse.de:ssh->venus.suse.de:33619 (ESTABLISHED)

sshd 8837 root 9u IPv6 294830 0t0 TCP localhost:x11 (LISTEN)

sshd 8837 root 10u IPv4 294831 0t0 TCP localhost:x11 (LISTEN)2.2.6 Kernel and udev Event Sequence Viewer: udevadm monitor #

udevadm monitor listens to the kernel uevents and

events sent out by a udev rule and prints the device path (DEVPATH) of

the event to the console. This is a sequence of events while connecting

a USB memory stick:

Note: Monitoring udev Events

Only root user is allowed to monitor udev events by running the

udevadm command.

UEVENT[1138806687] add@/devices/pci0000:00/0000:00:1d.7/usb4/4-2/4-2.2 UEVENT[1138806687] add@/devices/pci0000:00/0000:00:1d.7/usb4/4-2/4-2.2/4-2.2 UEVENT[1138806687] add@/class/scsi_host/host4 UEVENT[1138806687] add@/class/usb_device/usbdev4.10 UDEV [1138806687] add@/devices/pci0000:00/0000:00:1d.7/usb4/4-2/4-2.2 UDEV [1138806687] add@/devices/pci0000:00/0000:00:1d.7/usb4/4-2/4-2.2/4-2.2 UDEV [1138806687] add@/class/scsi_host/host4 UDEV [1138806687] add@/class/usb_device/usbdev4.10 UEVENT[1138806692] add@/devices/pci0000:00/0000:00:1d.7/usb4/4-2/4-2.2/4-2.2 UEVENT[1138806692] add@/block/sdb UEVENT[1138806692] add@/class/scsi_generic/sg1 UEVENT[1138806692] add@/class/scsi_device/4:0:0:0 UDEV [1138806693] add@/devices/pci0000:00/0000:00:1d.7/usb4/4-2/4-2.2/4-2.2 UDEV [1138806693] add@/class/scsi_generic/sg1 UDEV [1138806693] add@/class/scsi_device/4:0:0:0 UDEV [1138806693] add@/block/sdb UEVENT[1138806694] add@/block/sdb/sdb1 UDEV [1138806694] add@/block/sdb/sdb1 UEVENT[1138806694] mount@/block/sdb/sdb1 UEVENT[1138806697] umount@/block/sdb/sdb1

2.3 Processes #

2.3.1 Interprocess Communication: ipcs #

The command ipcs produces a list of the IPC resources

currently in use:

root # ipcs

------ Message Queues --------

key msqid owner perms used-bytes messages

------ Shared Memory Segments --------

key shmid owner perms bytes nattch status

0x00000000 65536 tux 600 524288 2 dest

0x00000000 98305 tux 600 4194304 2 dest

0x00000000 884738 root 600 524288 2 dest

0x00000000 786435 tux 600 4194304 2 dest

0x00000000 12058628 tux 600 524288 2 dest

0x00000000 917509 root 600 524288 2 dest

0x00000000 12353542 tux 600 196608 2 dest

0x00000000 12451847 tux 600 524288 2 dest

0x00000000 11567114 root 600 262144 1 dest

0x00000000 10911763 tux 600 2097152 2 dest

0x00000000 11665429 root 600 2336768 2 dest

0x00000000 11698198 root 600 196608 2 dest

0x00000000 11730967 root 600 524288 2 dest

------ Semaphore Arrays --------

key semid owner perms nsems

0xa12e0919 32768 tux 666 22.3.2 Process List: ps #

The command ps produces a list of processes. Most

parameters must be written without a minus sign. Refer to ps

--help for a brief help or to the man page for extensive help.

To list all processes with user and command line information, use

ps axu:

tux > ps axu

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

root 1 0.0 0.3 34376 4608 ? Ss Jul24 0:02 /usr/lib/systemd/systemd

root 2 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S Jul24 0:00 [kthreadd]

root 3 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S Jul24 0:00 [ksoftirqd/0]

root 5 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S< Jul24 0:00 [kworker/0:0H]

root 6 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S Jul24 0:00 [kworker/u2:0]

root 7 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S Jul24 0:00 [migration/0]

[...]

tux 12583 0.0 0.1 185980 2720 ? Sl 10:12 0:00 /usr/lib/gvfs/gvfs-mtp-volume-monitor

tux 12587 0.0 0.1 198132 3044 ? Sl 10:12 0:00 /usr/lib/gvfs/gvfs-gphoto2-volume-monitor

tux 12591 0.0 0.1 181940 2700 ? Sl 10:12 0:00 /usr/lib/gvfs/gvfs-goa-volume-monitor

tux 12594 8.1 10.6 1418216 163564 ? Sl 10:12 0:03 /usr/bin/gnome-shell

tux 12600 0.0 0.3 393448 5972 ? Sl 10:12 0:00 /usr/lib/gnome-settings-daemon-3.0/gsd-printer

tux 12625 0.0 0.6 227776 10112 ? Sl 10:12 0:00 /usr/lib/gnome-control-center-search-provider

tux 12626 0.5 1.5 890972 23540 ? Sl 10:12 0:00 /usr/bin/nautilus --no-default-window

[...]

To check how many sshd processes are running, use the

option -p together with the command

pidof, which lists the process IDs of the given

processes.

tux > ps -p $(pidof sshd)

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

1545 ? Ss 0:00 /usr/sbin/sshd -D

4608 ? Ss 0:00 sshd: root@pts/0

The process list can be formatted according to your needs. The option

-L returns a list of all keywords. Enter the following

command to issue a list of all processes sorted by memory usage:

tux > ps ax --format pid,rss,cmd --sort rss

PID RSS CMD

PID RSS CMD

2 0 [kthreadd]

3 0 [ksoftirqd/0]

4 0 [kworker/0:0]

5 0 [kworker/0:0H]

6 0 [kworker/u2:0]

7 0 [migration/0]

8 0 [rcu_bh]

[...]

12518 22996 /usr/lib/gnome-settings-daemon-3.0/gnome-settings-daemon

12626 23540 /usr/bin/nautilus --no-default-window

12305 32188 /usr/bin/Xorg :0 -background none -verbose

12594 164900 /usr/bin/gnome-shellUseful ps Calls #

ps aux--sort columnSort the output by column. Replace column with

pmemfor physical memory ratiopcpufor CPU ratiorssfor resident set size (non-swapped physical memory)ps axo pid,%cpu,rss,vsz,args,wchanShows every process, their PID, CPU usage ratio, memory size (resident and virtual), name, and their syscall.

ps axfo pid,argsShow a process tree.

2.3.3 Process Tree: pstree #

The command pstree produces a list of processes in

the form of a tree:

tux > pstree

systemd---accounts-daemon---{gdbus}

| |-{gmain}

|-at-spi-bus-laun---dbus-daemon

| |-{dconf worker}

| |-{gdbus}

| |-{gmain}

|-at-spi2-registr---{gdbus}

|-cron

|-2*[dbus-daemon]

|-dbus-launch

|-dconf-service---{gdbus}

| |-{gmain}

|-gconfd-2

|-gdm---gdm-simple-slav---Xorg

| | |-gdm-session-wor---gnome-session---gnome-setti+

| | | | |-gnome-shell+++

| | | | |-{dconf work+

| | | | |-{gdbus}

| | | | |-{gmain}

| | | |-{gdbus}

| | | |-{gmain}

| | |-{gdbus}

| | |-{gmain}

| |-{gdbus}

| |-{gmain}

[...]

The parameter -p adds the process ID to a given name.

To have the command lines displayed as well, use the -a

parameter:

2.3.4 Table of Processes: top #

The command top (an abbreviation of “table of

processes”) displays a list of processes that is refreshed every

two seconds. To terminate the program, press Q. The

parameter -n 1 terminates the program after a single

display of the process list. The following is an example output of the

command top -n 1:

tux > top -n 1

Tasks: 128 total, 1 running, 127 sleeping, 0 stopped, 0 zombie

%Cpu(s): 2.4 us, 1.2 sy, 0.0 ni, 96.3 id, 0.1 wa, 0.0 hi, 0.0 si, 0.0 st

KiB Mem: 1535508 total, 699948 used, 835560 free, 880 buffers

KiB Swap: 1541116 total, 0 used, 1541116 free. 377000 cached Mem

PID USER PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM TIME+ COMMAND

1 root 20 0 116292 4660 2028 S 0.000 0.303 0:04.45 systemd

2 root 20 0 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 kthreadd

3 root 20 0 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.07 ksoftirqd+

5 root 0 -20 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 kworker/0+

6 root 20 0 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 kworker/u+

7 root rt 0 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 migration+

8 root 20 0 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 rcu_bh

9 root 20 0 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.24 rcu_sched

10 root rt 0 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.01 watchdog/0

11 root 0 -20 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 khelper

12 root 20 0 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 kdevtmpfs

13 root 0 -20 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 netns

14 root 0 -20 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 writeback

15 root 0 -20 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 kintegrit+

16 root 0 -20 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 bioset

17 root 0 -20 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 crypto

18 root 0 -20 0 0 0 S 0.000 0.000 0:00.00 kblockdBy default the output is sorted by CPU usage (column , shortcut Shift–P). Use the following key combinations to change the sort field:

| Shift–M: Resident Memory () |

| Shift–N: Process ID () |

| Shift–T: Time () |

To use any other field for sorting, press F and select a field from the list. To toggle the sort order, Use Shift–R.

The parameter -U UID

monitors only the processes associated with a particular user. Replace

UID with the user ID of the user. Use

top -U $(id -u) to show processes of the current user

2.3.5 A top-like I/O Monitor: iotop #

The iotop utility displays a table of I/O usage by

processes or threads.

Note: Installing iotop

iotop is not installed by default. You need to

install it manually with zypper in iotop as

root.

iotop displays columns for the I/O bandwidth read and

written by each process during the sampling period. It also displays the

percentage of time the process spent while swapping in and while waiting

on I/O. For each process, its I/O priority (class/level) is shown. In

addition, the total I/O bandwidth read and written during the sampling

period is displayed at the top of the interface.

The ← and → keys change the sorting.

R reverses the sort order.

O toggles between showing all processes and threads (default view) and showing only those doing I/O. (This function is similar to adding

--onlyon command line.)P toggles between showing threads (default view) and processes. (This function is similar to

--only.)A toggles between showing the current I/O bandwidth (default view) and accumulated I/O operations since

iotopwas started. (This function is similar to--accumulated.)I lets you change the priority of a thread or a process's threads.

Q quits

iotop.Pressing any other key will force a refresh.

Following is an example output of the command iotop

--only, while find and

emacs are running:

tux > iotop --only

Total DISK READ: 50.61 K/s | Total DISK WRITE: 11.68 K/s

TID PRIO USER DISK READ DISK WRITE SWAPIN IO> COMMAND

3416 be/4 tux 50.61 K/s 0.00 B/s 0.00 % 4.05 % find /

275 be/3 root 0.00 B/s 3.89 K/s 0.00 % 2.34 % [jbd2/sda2-8]

5055 be/4 tux 0.00 B/s 3.89 K/s 0.00 % 0.04 % emacs

iotop can be also used in a batch mode

(-b) and its output stored in a file for later

analysis. For a complete set of options, see the manual page

(man 1 iotop).

2.3.6 Modify a process's niceness: nice and renice #

The kernel determines which processes require more CPU time than others

by the process's nice level, also called niceness. The higher the

“nice” level of a process is, the less CPU time it will

take from other processes. Nice levels range from -20 (the least

“nice” level) to 19. Negative values can only be set by

root.

Adjusting the niceness level is useful when running a non time-critical process that lasts long and uses large amounts of CPU time. For example, compiling a kernel on a system that also performs other tasks. Making such a process “nicer”, ensures that the other tasks, for example a Web server, will have a higher priority.

Calling nice without any parameters prints the

current niceness:

tux > nice

0

Running nice command

increments the current nice level for the given command by 10. Using

nice -n

level

command lets you specify a new niceness

relative to the current one.

To change the niceness of a running process, use

renice priority -p

process id, for example:

renice +5 3266

To renice all processes owned by a specific user, use the option

-u user.

Process groups are reniced by the option -g process

group id.

2.4 Memory #

2.4.1 Memory Usage: free #

The utility free examines RAM and swap usage. Details

of both free and used memory and swap areas are shown:

tux > free

total used free shared buffers cached

Mem: 32900500 32703448 197052 0 255668 5787364

-/+ buffers/cache: 26660416 6240084

Swap: 2046972 304680 1742292

The options -b, -k,

-m, -g show the output in bytes, KB,

MB, or GB, respectively. The parameter -d delay ensures

that the display is refreshed every delay

seconds. For example, free -d 1.5 produces an update

every 1.5 seconds.

2.4.2 Detailed Memory Usage: /proc/meminfo #

Use /proc/meminfo to get more detailed information

on memory usage than with free. Actually

free uses some of the data from this file. See an

example output from a 64-bit system below. Note that it slightly differs

on 32-bit systems because of different memory management:

MemTotal: 1942636 kB MemFree: 1294352 kB MemAvailable: 1458744 kB Buffers: 876 kB Cached: 278476 kB SwapCached: 0 kB Active: 368328 kB Inactive: 199368 kB Active(anon): 288968 kB Inactive(anon): 10568 kB Active(file): 79360 kB Inactive(file): 188800 kB Unevictable: 80 kB Mlocked: 80 kB SwapTotal: 2103292 kB SwapFree: 2103292 kB Dirty: 44 kB Writeback: 0 kB AnonPages: 288592 kB Mapped: 70444 kB Shmem: 11192 kB Slab: 40916 kB SReclaimable: 17712 kB SUnreclaim: 23204 kB KernelStack: 2000 kB PageTables: 10996 kB NFS_Unstable: 0 kB Bounce: 0 kB WritebackTmp: 0 kB CommitLimit: 3074608 kB Committed_AS: 1407208 kB VmallocTotal: 34359738367 kB VmallocUsed: 145996 kB VmallocChunk: 34359588844 kB HardwareCorrupted: 0 kB AnonHugePages: 86016 kB HugePages_Total: 0 HugePages_Free: 0 HugePages_Rsvd: 0 HugePages_Surp: 0 Hugepagesize: 2048 kB DirectMap4k: 79744 kB DirectMap2M: 2017280 kB

These entries stand for the following:

Total amount of RAM.

Amount of unused RAM.

Estimate of how much memory is available for starting new applications without swapping.

File buffer cache in RAM

Page cache in RAM. This excludes buffer cache and swap cache, but includes memory.

Page cache for swapped-out memory.

- , ,

Recently used memory that will not be reclaimed unless necessary or on explicit request. is the sum of and :

tracks swap-backed memory. This includes private and shared anonymous mappings and private file pages after copy-on-write.

tracks other file-system backed memory.

- , ,

Less recently used memory that will usually be reclaimed first. is the sum of and :

tracks swap backed memory. This includes private and shared anonymous mappings and private file pages after copy-on-write.

tracks other file-system backed memory.

Amount of memory that cannot be reclaimed (for example, because it is or used as a RAM disk).

Amount of memory that is backed by the

mlocksystem call.mlockallows processes to define which part of physical RAM their virtual memory should be mapped to. However,mlockdoes not guarantee this placement.Amount of swap space.

Amount of unused swap space.

Amount of memory waiting to be written to disk, because it contains changes compared to the backing storage.

Amount of memory that is currently being written to disk.

Memory claimed with the

mmapsystem call.Memory shared between groups of processes, such as IPC data,

tmpfsdata and shared anonymous memory.Memory allocation for internal data structures of the kernel.

Slab section that can be reclaimed, such as caches (inode, dentry, etc.).

Slab section that cannot be reclaimed.

Amount of kernel space memory used by applications (through system calls).

Amount of memory dedicated to page tables of all processes.

NFS pages that have already been sent to the server, but are not yet committed there.

Memory used for bounce buffers of block devices.

Memory used by FUSE for temporary writeback buffers.

Amount of memory available to the system based on the overcommit ratio setting. This is only enforced if strict overcommit accounting is enabled.

An approximation of the total amount of memory (RAM and swap) that the current workload would need in the worst case.

Amount of allocated kernel virtual address space.

Amount of used kernel virtual address space.

The largest contiguous block of available kernel virtual address space.

Amount of failed memory (can only be detected when using ECC RAM).

Anonymous hugepages that are mapped into userspace page tables. These are allocated transparently for processes without being specifically requested, therefore they are also known as transparent hugepages (THP).

Number of preallocated hugepages for use by

SHM_HUGETLBandMAP_HUGETLBor through thehugetlbfsfile system, as defined in/proc/sys/vm/nr_hugepagesNumber of hugepages available.

Number of hugepages that are committed.

Number of hugepages available beyond (“surplus”), as defined in

/proc/sys/vm/nr_overcommit_hugepages.Size of a hugepage, on AMD64/Intel 64—the default is 2048 KB.

- etc.

Amount of kernel memory that is mapped to pages with a given size (in the example: 4 kB).

2.4.3 Process Memory Usage: smaps #

Exactly determining how much memory a certain process is consuming is

not possible with standard tools like top or

ps. Use the smaps subsystem, introduced in Kernel

2.6.14, if you need exact data. It can be found at

/proc/pid/smaps and

shows you the number of clean and dirty memory pages the process with

the ID PID is using at that time. It

differentiates between shared and private memory, so you can see

how much memory the process is using without including memory shared

with other processes. For more information see

/usr/src/linux/Documentation/filesystems/proc.txt

(requires the package

kernel-source to be

installed).

smaps is expensive to read. Therefore it is not recommended to monitor it regularly, but only when closely monitoring a certain process.

2.5 Networking #

Tip: Traffic Shaping

In case the network bandwidth is lower than expected, you should first check if any traffic shaping rules are active for your network segment.

2.5.1 Basic Network Diagnostics: ip #

ip is a powerful tool to set up and control network

interfaces. You can also use it to quickly view basic statistics about

network interfaces of the system. For example, whether the interface is

up or how many errors, dropped packets, or packet collisions there are.

If you run ip with no additional parameter, it

displays a help output. To list all network interfaces, enter

ip addr show (or abbreviated as ip

a). ip addr show up lists only running

network interfaces. ip -s link show

device lists statistics for the specified

interface only:

root # ip -s link show br0

6: br0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP mode DEFAULT

link/ether 00:19:d1:72:d4:30 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

RX: bytes packets errors dropped overrun mcast

6346104756 9265517 0 10860 0 0

TX: bytes packets errors dropped carrier collsns

3996204683 3655523 0 0 0 0

ip can also be used to show interfaces

(link), routing tables (route), and

much more—refer to man 8 ip for details.

root # ip route

default via 192.168.2.1 dev eth1

192.168.2.0/24 dev eth0 proto kernel scope link src 192.168.2.100

192.168.2.0/24 dev eth1 proto kernel scope link src 192.168.2.101

192.168.2.0/24 dev eth2 proto kernel scope link src 192.168.2.102root # ip link

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN mode DEFAULT group default

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

2: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP mode DEFAULT group default qlen 1000

link/ether 52:54:00:44:30:51 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

3: eth1: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP mode DEFAULT group default qlen 1000

link/ether 52:54:00:a3:c1:fb brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

4: eth2: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP mode DEFAULT group default qlen 1000

link/ether 52:54:00:32:a4:09 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff2.5.2

Show the Network Usage of Processes: nethogs

#

In some cases, for example if the network traffic suddenly becomes very

high, it is desirable to quickly find out which application(s) is/are

causing the traffic. nethogs, a tool with a design

similar to top, shows incoming and outgoing traffic for

all relevant processes:

PID USER PROGRAM DEV SENT RECEIVED 27145 root zypper eth0 5.719 391.749 KB/sec ? root ..0:113:80c0:8080:10:160:0:100:30015 0.102 2.326 KB/sec 26635 tux /usr/lib64/firefox/firefox eth0 0.026 0.026 KB/sec ? root ..0:113:80c0:8080:10:160:0:100:30045 0.000 0.021 KB/sec ? root ..0:113:80c0:8080:10:160:0:100:30045 0.000 0.018 KB/sec ? root ..0:113:80c0:8080:10:160:0:100:30015 0.000 0.018 KB/sec ? root ..0:113:80c0:8080:10:160:0:100:30045 0.000 0.017 KB/sec ? root ..0:113:80c0:8080:10:160:0:100:30045 0.000 0.017 KB/sec ? root ..0:113:80c0:8080:10:160:0:100:30045 0.069 0.000 KB/sec ? root unknown TCP 0.000 0.000 KB/sec TOTAL 5.916 394.192 KB/sec

Like in top, nethogs features

interactive commands:

| M: cycle between display modes (kb/s, kb, b, mb) |

| R: sort by |

| S: sort by |

| Q: quit |

2.5.3 Ethernet Cards in Detail: ethtool #

ethtool can display and change detailed aspects of

your Ethernet network device. By default it prints the current setting

of the specified device.

root # ethtool eth0

Settings for eth0:

Supported ports: [ TP ]

Supported link modes: 10baseT/Half 10baseT/Full

100baseT/Half 100baseT/Full

1000baseT/Full

Supports auto-negotiation: Yes

Advertised link modes: 10baseT/Half 10baseT/Full

100baseT/Half 100baseT/Full

1000baseT/Full

Advertised pause frame use: No

[...]

Link detected: yes

The following table shows ethtool options that you

can use to query the device for specific information:

Table 2.1: List of Query Options of ethtool #

|

|

it queries the device for |

|---|---|

|

-a |

pause parameter information |

|

-c |

interrupt coalescing information |

|

-g |

Rx/Tx (receive/transmit) ring parameter information |

|

-i |

associated driver information |

|

-k |

offload information |

|

-S |

NIC and driver-specific statistics |

2.5.4 Show the Network Status: ss #

ss is a tool to dump socket statistics and replaces

the netstat command. To show a list of all

connections use ss parameters:

root # ss

Netid State Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address:Port Peer Address:Port

u_str ESTAB 0 0 * 14082 * 14083

u_str ESTAB 0 0 * 18582 * 18583

u_str ESTAB 0 0 * 19449 * 19450

u_str ESTAB 0 0 @/tmp/dbus-gmUUwXABPV 18784 * 18783

u_str ESTAB 0 0 /var/run/dbus/system_bus_socket 19383 * 19382

u_str ESTAB 0 0 @/tmp/dbus-gmUUwXABPV 18617 * 18616

u_str ESTAB 0 0 @/tmp/dbus-58TPPDv8qv 19352 * 19351

u_str ESTAB 0 0 * 17658 * 17657

u_str ESTAB 0 0 * 17693 * 17694

[..]To show all network ports currently open, use the following command:

root # ss -l

Netid State Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address:Port Peer Address:Port

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:4195117 *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:wickedd-auto4/811 *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:wickedd-dhcp4/813 *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:4195121 *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:4195115 *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:wickedd-dhcp6/814 *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:kernel *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:wickedd/817 *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:4195118 *

nl UNCONN 0 0 rtnl:nscd/706 *

nl UNCONN 4352 0 tcpdiag:ss/2381 *

[...]

When displaying network connections, you can specify the socket type to

display: TCP (-t) or UDP (-u) for

example. The -p option shows the PID and name of the

program to which each socket belongs.

The following example lists all TCP connections and the programs using

these connections. The -a option make sure all

established connections (listening and non-listening) are shown. The

-p option shows the PID and name of the program to

which each socket belongs.

root # ss -t -a -p

State Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address:Port Peer Address:Port

LISTEN 0 128 *:ssh *:* users:(("sshd",1551,3))

LISTEN 0 100 127.0.0.1:smtp *:* users:(("master",1704,13))

ESTAB 0 132 10.120.65.198:ssh 10.120.4.150:55715 users:(("sshd",2103,5))

LISTEN 0 128 :::ssh :::* users:(("sshd",1551,4))

LISTEN 0 100 ::1:smtp :::* users:(("master",1704,14))2.6 The /proc File System #

The /proc file system is a pseudo file system in

which the kernel reserves important information in the form of virtual

files. For example, display the CPU type with this command:

tux > cat /proc/cpuinfo

processor : 0

vendor_id : GenuineIntel

cpu family : 6

model : 30

model name : Intel(R) Core(TM) i5 CPU 750 @ 2.67GHz

stepping : 5

microcode : 0x6

cpu MHz : 1197.000

cache size : 8192 KB

physical id : 0

siblings : 4

core id : 0

cpu cores : 4

apicid : 0

initial apicid : 0

fpu : yes

fpu_exception : yes

cpuid level : 11

wp : yes

flags : fpu vme de pse tsc msr pae mce cx8 apic sep mtrr pge mca cmov pat pse36 clflush dts acpi mmx fxsr sse sse2 ss ht tm pbe syscall nx rdtscp lm constant_tsc arch_perfmon pebs bts rep_good nopl xtopology nonstop_tsc aperfmperf pni dtes64 monitor ds_cpl vmx smx est tm2 ssse3 cx16 xtpr pdcm sse4_1 sse4_2 popcnt lahf_lm ida dtherm tpr_shadow vnmi flexpriority ept vpid

bogomips : 5333.85

clflush size : 64

cache_alignment : 64

address sizes : 36 bits physical, 48 bits virtual

power management:

[...]Tip: Detailed Processor Information

Detailed information about the processor on the x86_64 architecture is

also available by running x86info.

Query the allocation and use of interrupts with the following command:

tux > cat /proc/interrupts

CPU0 CPU1 CPU2 CPU3

0: 121 0 0 0 IO-APIC-edge timer

8: 0 0 0 1 IO-APIC-edge rtc0

9: 0 0 0 0 IO-APIC-fasteoi acpi

16: 0 11933 0 0 IO-APIC-fasteoi ehci_hcd:+

18: 0 0 0 0 IO-APIC-fasteoi i801_smbus

19: 0 117978 0 0 IO-APIC-fasteoi ata_piix,+

22: 0 0 3275185 0 IO-APIC-fasteoi enp5s1

23: 417927 0 0 0 IO-APIC-fasteoi ehci_hcd:+

40: 2727916 0 0 0 HPET_MSI-edge hpet2

41: 0 2749134 0 0 HPET_MSI-edge hpet3

42: 0 0 2759148 0 HPET_MSI-edge hpet4

43: 0 0 0 2678206 HPET_MSI-edge hpet5

45: 0 0 0 0 PCI-MSI-edge aerdrv, P+

46: 0 0 0 0 PCI-MSI-edge PCIe PME,+

47: 0 0 0 0 PCI-MSI-edge PCIe PME,+

48: 0 0 0 0 PCI-MSI-edge PCIe PME,+

49: 0 0 0 387 PCI-MSI-edge snd_hda_i+

50: 933117 0 0 0 PCI-MSI-edge nvidia

NMI: 2102 2023 2031 1920 Non-maskable interrupts

LOC: 92 71 57 41 Local timer interrupts

SPU: 0 0 0 0 Spurious interrupts

PMI: 2102 2023 2031 1920 Performance monitoring int+

IWI: 47331 45725 52464 46775 IRQ work interrupts

RTR: 2 0 0 0 APIC ICR read retries

RES: 472911 396463 339792 323820 Rescheduling interrupts

CAL: 48389 47345 54113 50478 Function call interrupts

TLB: 28410 26804 24389 26157 TLB shootdowns

TRM: 0 0 0 0 Thermal event interrupts

THR: 0 0 0 0 Threshold APIC interrupts

MCE: 0 0 0 0 Machine check exceptions

MCP: 40 40 40 40 Machine check polls

ERR: 0

MIS: 0

The address assignment of executables and libraries is contained in the

maps file:

tux > cat /proc/self/maps

08048000-0804c000 r-xp 00000000 03:03 17753 /bin/cat

0804c000-0804d000 rw-p 00004000 03:03 17753 /bin/cat

0804d000-0806e000 rw-p 0804d000 00:00 0 [heap]

b7d27000-b7d5a000 r--p 00000000 03:03 11867 /usr/lib/locale/en_GB.utf8/

b7d5a000-b7e32000 r--p 00000000 03:03 11868 /usr/lib/locale/en_GB.utf8/

b7e32000-b7e33000 rw-p b7e32000 00:00 0

b7e33000-b7f45000 r-xp 00000000 03:03 8837 /lib/libc-2.3.6.so

b7f45000-b7f46000 r--p 00112000 03:03 8837 /lib/libc-2.3.6.so

b7f46000-b7f48000 rw-p 00113000 03:03 8837 /lib/libc-2.3.6.so

b7f48000-b7f4c000 rw-p b7f48000 00:00 0

b7f52000-b7f53000 r--p 00000000 03:03 11842 /usr/lib/locale/en_GB.utf8/

[...]

b7f5b000-b7f61000 r--s 00000000 03:03 9109 /usr/lib/gconv/gconv-module

b7f61000-b7f62000 r--p 00000000 03:03 9720 /usr/lib/locale/en_GB.utf8/

b7f62000-b7f76000 r-xp 00000000 03:03 8828 /lib/ld-2.3.6.so

b7f76000-b7f78000 rw-p 00013000 03:03 8828 /lib/ld-2.3.6.so

bfd61000-bfd76000 rw-p bfd61000 00:00 0 [stack]

ffffe000-fffff000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso]A lot more information can be obtained from the /proc file system. Some of the important files and their contents are:

/proc/devicesAvailable devices

/proc/modulesKernel modules loaded

/proc/cmdlineKernel command line

/proc/meminfoDetailed information about memory usage

/proc/config.gzgzip-compressed configuration file of the kernel currently running- /proc/PID/

Find information about processes currently running in the

/proc/NNN directories, where NNN is the process ID (PID) of the relevant process. Every process can find its own characteristics in/proc/self/.

Further information is available in the text file

/usr/src/linux/Documentation/filesystems/proc.txt

(this file is available when the package

kernel-source is installed).

2.6.1 procinfo #

Important information from the /proc file system is

summarized by the command procinfo:

tux > procinfo

Linux 3.11.10-17-desktop (geeko@buildhost) (gcc 4.8.1 20130909) #1 4CPU [jupiter.example.com]

Memory: Total Used Free Shared Buffers Cached

Mem: 8181908 8000632 181276 0 85472 2850872

Swap: 10481660 1576 10480084

Bootup: Mon Jul 28 09:54:13 2014 Load average: 1.61 0.85 0.74 2/904 25949

user : 1:54:41.84 12.7% page in : 2107312 disk 1: 52212r 20199w

nice : 0:00:00.46 0.0% page out: 1714461 disk 2: 19387r 10928w

system: 0:25:38.00 2.8% page act: 466673 disk 3: 548r 10w

IOwait: 0:04:16.45 0.4% page dea: 272297

hw irq: 0:00:00.42 0.0% page flt: 105754526

sw irq: 0:01:26.48 0.1% swap in : 0

idle : 12:14:43.65 81.5% swap out: 394

guest : 0:02:18.59 0.2%

uptime: 3:45:22.24 context : 99809844

irq 0: 121 timer irq 41: 3238224 hpet3

irq 8: 1 rtc0 irq 42: 3251898 hpet4

irq 9: 0 acpi irq 43: 3156368 hpet5

irq 16: 14589 ehci_hcd:usb1 irq 45: 0 aerdrv, PCIe PME

irq 18: 0 i801_smbus irq 46: 0 PCIe PME, pciehp

irq 19: 124861 ata_piix, ata_piix, f irq 47: 0 PCIe PME, pciehp

irq 22: 3742817 enp5s1 irq 48: 0 PCIe PME, pciehp

irq 23: 479248 ehci_hcd:usb2 irq 49: 387 snd_hda_intel

irq 40: 3216894 hpet2 irq 50: 1088673 nvidia

To see all the information, use the parameter -a. The

parameter -nN produces updates of the information every

N seconds. In this case, terminate the

program by pressing Q.

By default, the cumulative values are displayed. The parameter

-d produces the differential values. procinfo

-dn5 displays the values that have changed in the last five

seconds:

2.6.2 System Control Parameters: /proc/sys/ #

System control parameters are used to modify the Linux kernel parameters

at runtime. They reside in /proc/sys/ and can be

viewed and modified with the sysctl command. To list

all parameters, run sysctl -a. A

single parameter can be listed with sysctl

parameter name.

Parameters are grouped into categories and can be listed with

sysctl category or by

listing the contents of the respective directories. The most important

categories are listed below. The links to further readings require the

installation of the package

kernel-source.

sysctl dev(/proc/sys/abi/)Device-specific information.

sysctl fs(/proc/sys/fs/)Used file handles, quotas, and other file system-oriented parameters. For details see

/usr/src/linux/Documentation/sysctl/fs.txt.sysctl kernel(/proc/sys/kernel/)Information about the task scheduler, system shared memory, and other kernel-related parameters. For details see

/usr/src/linux/Documentation/sysctl/kernel.txtsystctl net(/proc/sys/net/)Information about network bridges, and general network parameters (mainly the

ipv4/subdirectory). For details see/usr/src/linux/Documentation/sysctl/net.txtsysctl vm(/proc/sys/vm/)Entries in this path relate to information about the virtual memory, swapping, and caching. For details see

/usr/src/linux/Documentation/sysctl/vm.txt

To set or change a parameter for the current session, use the command

sysctl -w

parameter=value.

To permanently change a setting, add a line

parameter=value to

/etc/sysctl.conf.

2.7 Hardware Information #

2.7.1 PCI Resources: lspci #

Note: Accessing PCI configuration.

Most operating systems require root user privileges to grant access to the computer's PCI configuration.

The command lspci lists the PCI resources:

root # lspci

00:00.0 Host bridge: Intel Corporation 82845G/GL[Brookdale-G]/GE/PE \

DRAM Controller/Host-Hub Interface (rev 01)

00:01.0 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 82845G/GL[Brookdale-G]/GE/PE \

Host-to-AGP Bridge (rev 01)

00:1d.0 USB Controller: Intel Corporation 82801DB/DBL/DBM \

(ICH4/ICH4-L/ICH4-M) USB UHCI Controller #1 (rev 01)

00:1d.1 USB Controller: Intel Corporation 82801DB/DBL/DBM \

(ICH4/ICH4-L/ICH4-M) USB UHCI Controller #2 (rev 01)

00:1d.2 USB Controller: Intel Corporation 82801DB/DBL/DBM \

(ICH4/ICH4-L/ICH4-M) USB UHCI Controller #3 (rev 01)

00:1d.7 USB Controller: Intel Corporation 82801DB/DBM \

(ICH4/ICH4-M) USB2 EHCI Controller (rev 01)

00:1e.0 PCI bridge: Intel Corporation 82801 PCI Bridge (rev 81)

00:1f.0 ISA bridge: Intel Corporation 82801DB/DBL (ICH4/ICH4-L) \

LPC Interface Bridge (rev 01)

00:1f.1 IDE interface: Intel Corporation 82801DB (ICH4) IDE \

Controller (rev 01)

00:1f.3 SMBus: Intel Corporation 82801DB/DBL/DBM (ICH4/ICH4-L/ICH4-M) \

SMBus Controller (rev 01)

00:1f.5 Multimedia audio controller: Intel Corporation 82801DB/DBL/DBM \

(ICH4/ICH4-L/ICH4-M) AC'97 Audio Controller (rev 01)

01:00.0 VGA compatible controller: Matrox Graphics, Inc. G400/G450 (rev 85)

02:08.0 Ethernet controller: Intel Corporation 82801DB PRO/100 VE (LOM) \

Ethernet Controller (rev 81)

Using -v results in a more detailed listing:

root # lspci -v

[...]

00:03.0 Ethernet controller: Intel Corporation 82540EM Gigabit Ethernet \

Controller (rev 02)

Subsystem: Intel Corporation PRO/1000 MT Desktop Adapter

Flags: bus master, 66MHz, medium devsel, latency 64, IRQ 19

Memory at f0000000 (32-bit, non-prefetchable) [size=128K]

I/O ports at d010 [size=8]

Capabilities: [dc] Power Management version 2

Capabilities: [e4] PCI-X non-bridge device

Kernel driver in use: e1000

Kernel modules: e1000

Information about device name resolution is obtained from the file

/usr/share/pci.ids. PCI IDs not listed in this file

are marked “Unknown device.”

The parameter -vv produces all the information that

could be queried by the program. To view the pure numeric values, use

the parameter -n.

2.7.2 USB Devices: lsusb #

The command lsusb lists all USB devices. With the

option -v, print a more detailed list. The detailed

information is read from the directory

/proc/bus/usb/. The following is the output of

lsusb with these USB devices attached: hub, memory

stick, hard disk and mouse.

root # lsusb

Bus 004 Device 007: ID 0ea0:2168 Ours Technology, Inc. Transcend JetFlash \

2.0 / Astone USB Drive

Bus 004 Device 006: ID 04b4:6830 Cypress Semiconductor Corp. USB-2.0 IDE \

Adapter

Bus 004 Device 005: ID 05e3:0605 Genesys Logic, Inc.

Bus 004 Device 001: ID 0000:0000

Bus 003 Device 001: ID 0000:0000

Bus 002 Device 001: ID 0000:0000

Bus 001 Device 005: ID 046d:c012 Logitech, Inc. Optical Mouse

Bus 001 Device 001: ID 0000:00002.7.3 MCELog: Machine Check Exceptions (MCE) #

The mcelog package logs and

parses/translates Machine Check Exceptions (MCE) on hardware errors

(also including memory errors). Formerly this has been done by a cron

job executed hourly. Now hardware errors are immediately processed by an

mcelog daemon.

However, the mcelog service is not enabled by default, resulting in memory and CPU errors also not being logged by default. In addition, mcelog has a new feature to also handle predictive bad page offlining and automatic core offlining when cache errors happen.

The service can either be enabled and started via the YaST system services editor or via command line:

systemctl enable mcelog systemctl start mcelog

2.7.4 x86_64: dmidecode: DMI table decoder #

dmidecode shows the machine's DMI table containing

information such as serial numbers and BIOS revisions of the hardware

root # dmidecode

# dmidecode 2.12

SMBIOS 2.5 present.

27 structures occupying 1298 bytes.

Table at 0x000EB250.

Handle 0x0000, DMI type 4, 35 bytes

Processor Information

Socket Designation: J1PR

Type: Central Processor

Family: Other

Manufacturer: Intel(R) Corporation

ID: E5 06 01 00 FF FB EB BF

Version: Intel(R) Core(TM) i5 CPU 750 @ 2.67GHz

Voltage: 1.1 V

External Clock: 133 MHz

Max Speed: 4000 MHz

Current Speed: 2667 MHz

Status: Populated, Enabled

Upgrade: Other

L1 Cache Handle: 0x0004

L2 Cache Handle: 0x0003

L3 Cache Handle: 0x0001

Serial Number: Not Specified

Asset Tag: Not Specified

Part Number: Not Specified

[..]2.8 Files and File Systems #

2.8.1 Determine the File Type: file #

The command file determines the type of a file or a

list of files by checking /usr/share/misc/magic.

tux > file /usr/bin/file

/usr/bin/file: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), \

for GNU/Linux 2.6.4, dynamically linked (uses shared libs), stripped

The parameter -f list

specifies a file with a list of file names to examine. The

-z allows file to look inside

compressed files:

tux >file /usr/share/man/man1/file.1.gz /usr/share/man/man1/file.1.gz: gzip compressed data, from Unix, max compressiontux >file -z /usr/share/man/man1/file.1.gz /usr/share/man/man1/file.1.gz: troff or preprocessor input text \ (gzip compressed data, from Unix, max compression)

The parameter -i outputs a mime type string rather than

the traditional description.

tux > file -i /usr/share/misc/magic

/usr/share/misc/magic: text/plain charset=utf-82.8.2 File Systems and Their Usage: mount, df and du #

The command mount shows which file system (device and

type) is mounted at which mount point:

root # mount

/dev/sda2 on / type ext4 (rw,acl,user_xattr)

proc on /proc type proc (rw)

sysfs on /sys type sysfs (rw)

debugfs on /sys/kernel/debug type debugfs (rw)

devtmpfs on /dev type devtmpfs (rw,mode=0755)

tmpfs on /dev/shm type tmpfs (rw,mode=1777)

devpts on /dev/pts type devpts (rw,mode=0620,gid=5)

/dev/sda3 on /home type ext3 (rw)

securityfs on /sys/kernel/security type securityfs (rw)

fusectl on /sys/fs/fuse/connections type fusectl (rw)

gvfs-fuse-daemon on /home/tux/.gvfs type fuse.gvfs-fuse-daemon \

(rw,nosuid,nodev,user=tux)

Obtain information about total usage of the file systems with the

command df. The parameter -h (or

--human-readable) transforms the output into a form

understandable for common users.

tux > df -h

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/sda2 20G 5,9G 13G 32% /

devtmpfs 1,6G 236K 1,6G 1% /dev

tmpfs 1,6G 668K 1,6G 1% /dev/shm

/dev/sda3 208G 40G 159G 20% /home

Display the total size of all the files in a given directory and its

subdirectories with the command du. The parameter

-s suppresses the output of detailed information and

gives only a total for each argument. -h again

transforms the output into a human-readable form:

tux > du -sh /opt

192M /opt2.8.3 Additional Information about ELF Binaries #

Read the content of binaries with the readelf

utility. This even works with ELF files that were built for other

hardware architectures:

tux > readelf --file-header /bin/ls

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Advanced Micro Devices X86-64

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x402540

Start of program headers: 64 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 95720 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 64 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 56 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 9

Size of section headers: 64 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 32

Section header string table index: 312.8.4 File Properties: stat #

The command stat displays file properties:

tux > stat /etc/profile

File: `/etc/profile'

Size: 9662 Blocks: 24 IO Block: 4096 regular file

Device: 802h/2050d Inode: 132349 Links: 1

Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 0/ root)

Access: 2009-03-20 07:51:17.000000000 +0100

Modify: 2009-01-08 19:21:14.000000000 +0100

Change: 2009-03-18 12:55:31.000000000 +0100

The parameter --file-system produces details of the

properties of the file system in which the specified file is located:

tux > stat /etc/profile --file-system

File: "/etc/profile"

ID: d4fb76e70b4d1746 Namelen: 255 Type: ext2/ext3

Block size: 4096 Fundamental block size: 4096

Blocks: Total: 2581445 Free: 1717327 Available: 1586197

Inodes: Total: 655776 Free: 4903122.9 User Information #

2.9.1 User Accessing Files: fuser #

It can be useful to determine what processes or users are currently

accessing certain files. Suppose, for example, you want to unmount a

file system mounted at /mnt.

umount returns "device is busy." The command

fuser can then be used to determine what processes

are accessing the device:

tux > fuser -v /mnt/*

USER PID ACCESS COMMAND

/mnt/notes.txt tux 26597 f.... less

Following termination of the less process, which was

running on another terminal, the file system can successfully be

unmounted. When used with -k option,

fuser will terminate processes accessing the file as

well.

2.9.2 Who Is Doing What: w #

With the command w, find out who is logged onto the

system and what each user is doing. For example:

tux > w