- Preface

- 1 Security and confidentiality

- I Authentication

- II Local security

- 9 Physical security

- 10 Software management

- 11 File management

- 12 Encrypting partitions and files

- 13 Storage encryption for hosted applications with cryptctl

- 14 User management

- 15 Restricting

cronandat - 16 Spectre/Meltdown checker

- 17 Configuring security settings with YaST

- 18 The Polkit authentication framework

- 19 Access control lists in Linux

- 20 Intrusion detection with AIDE

- III Network security

- IV Confining privileges with AppArmor

- 27 Introducing AppArmor

- 28 Getting started

- 29 Immunizing programs

- 30 Profile components and syntax

- 31 AppArmor profile repositories

- 32 Building and managing profiles with YaST

- 33 Building profiles from the command line

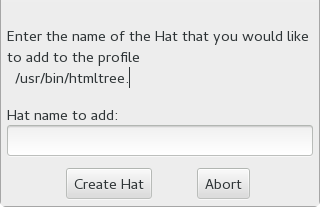

- 34 Profiling your Web applications using ChangeHat

- 35 Confining users with

pam_apparmor - 36 Managing profiled applications

- 37 Support

- 38 AppArmor glossary

- V SELinux

- VI The Linux Audit Framework

- A GNU licenses

openSUSE Leap 15.6

Security and Hardening Guide

Abstract#

This guide introduces basic concepts of system security and describes the usage of security software included with the product, such as AppArmor, SELinux, or the auditing system. The guide also supports system administrators in hardening an installation.

- Preface

- 1 Security and confidentiality

- I Authentication

- 2 Authentication with PAM

- 3 Using NIS

- 4 Setting up authentication clients using YaST

- 5 LDAP with 389 Directory Server

- 5.1 Structure of an LDAP directory tree

- 5.2 Creating and managing a Docker container for 389 Directory Server

- 5.3 Installing 389 Directory Server

- 5.4 Firewall configuration

- 5.5 Backing up and restoring 389 Directory Server

- 5.6 Managing LDAP users and groups

- 5.7 Managing plug-ins

- 5.8 Using SSSD to manage LDAP authentication

- 5.9 Migrating to 389 Directory Server from OpenLDAP

- 5.10 Importing TLS server certificates and keys

- 5.11 Setting up replication

- 5.12 Synchronizing with Microsoft Active Directory

- 5.13 More information

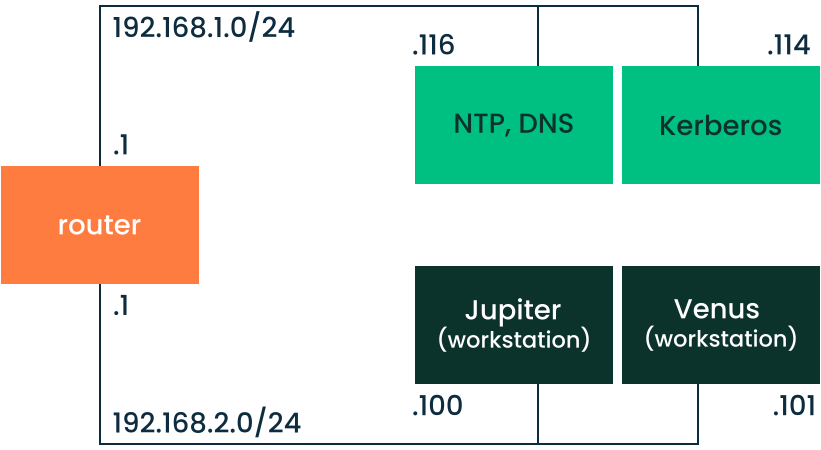

- 6 Network authentication with Kerberos

- 7 Active Directory support

- 8 Setting up a freeRADIUS server

- II Local security

- 9 Physical security

- 10 Software management

- 11 File management

- 12 Encrypting partitions and files

- 13 Storage encryption for hosted applications with cryptctl

- 13.1 Setting up a

cryptctlserver - 13.2 Setting up a

cryptctlclient - 13.3 Configuring /etc/fstab for LUKS volumes

- 13.4 Checking partition unlock status using server-side commands

- 13.5 Unlocking encrypted partitions manually

- 13.6 Maintenance downtime procedure

- 13.7 Setting up an HA environment for cryptctl-server service

- 13.8 More information

- 13.1 Setting up a

- 14 User management

- 14.1 Various account checks

- 14.2 Enabling password aging

- 14.3 Stronger password enforcement

- 14.4 Password and login management with PAM

- 14.5 Restricting

rootlogins - 14.6 Restricting

sudousers - 14.7 Setting an inactivity timeout for interactive shell sessions

- 14.8 Preventing accidental denial of service

- 14.9 Displaying login banners

- 14.10 Connection accounting utilities

- 15 Restricting

cronandat - 16 Spectre/Meltdown checker

- 17 Configuring security settings with YaST

- 18 The Polkit authentication framework

- 19 Access control lists in Linux

- 20 Intrusion detection with AIDE

- III Network security

- 21 X Window System and X authentication

- 22 Securing network operations with OpenSSH

- 22.1 OpenSSH overview

- 22.2 Server hardening

- 22.3 Password authentication

- 22.4 Managing user and host encryption keys

- 22.5 Rotating host keys

- 22.6 Public key authentication

- 22.7 Passphrase-less public key authentication

- 22.8 OpenSSH certificate authentication

- 22.9 Automated public key logins with gnome-keyring

- 22.10 Automated public key logins with ssh-agent

- 22.11 Changing an SSH private key passphrase

- 22.12 Retrieving a key fingerprint

- 22.13 Starting X11 applications on a remote host

- 22.14 Agent forwarding

- 22.15

scp—secure copy - 22.16

sftp—secure file transfer - 22.17 Port forwarding (SSH tunneling)

- 22.18 More information

- 22.19 Stopping SSH Brute Force Attacks with Fail2Ban

- 23 Masquerading and firewalls

- 24 Configuring a VPN server

- 25 Managing a PKI with XCA, X certificate and key manager

- 26 Improving network security with

sysctlvariables

- IV Confining privileges with AppArmor

- 27 Introducing AppArmor

- 28 Getting started

- 29 Immunizing programs

- 30 Profile components and syntax

- 30.1 Breaking an AppArmor profile into its parts

- 30.2 Profile types

- 30.3 Include statements

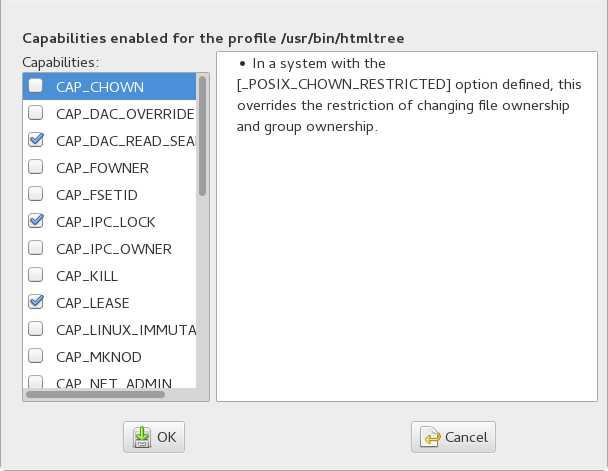

- 30.4 Capability entries (POSIX.1e)

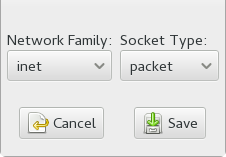

- 30.5 Network access control

- 30.6 Profile names, flags, paths, and globbing

- 30.7 File permission access modes

- 30.8 Mount rules

- 30.9 Pivot root rules

- 30.10 PTrace rules

- 30.11 Signal rules

- 30.12 Execute modes

- 30.13 Resource limit control

- 30.14 Auditing rules

- 31 AppArmor profile repositories

- 32 Building and managing profiles with YaST

- 33 Building profiles from the command line

- 34 Profiling your Web applications using ChangeHat

- 35 Confining users with

pam_apparmor - 36 Managing profiled applications

- 37 Support

- 38 AppArmor glossary

- V SELinux

- VI The Linux Audit Framework

- 40 Understanding Linux audit

- 40.1 Introducing the components of Linux audit

- 40.2 Configuring the audit daemon

- 40.3 Controlling the audit system using

auditctl - 40.4 Passing parameters to the audit system

- 40.5 Understanding the audit logs and generating reports

- 40.6 Querying the audit daemon logs with

ausearch - 40.7 Analyzing processes with

autrace - 40.8 Visualizing audit data

- 40.9 Relaying audit event notifications

- 41 Setting up the Linux audit framework

- 42 Introducing an audit rule set

- 42.1 Adding basic audit configuration parameters

- 42.2 Adding watches on audit log files and configuration files

- 42.3 Monitoring file system objects

- 42.4 Monitoring security configuration files and databases

- 42.5 Monitoring miscellaneous system calls

- 42.6 Filtering system call arguments

- 42.7 Managing audit event records using keys

- 43 Useful resources

- A GNU licenses

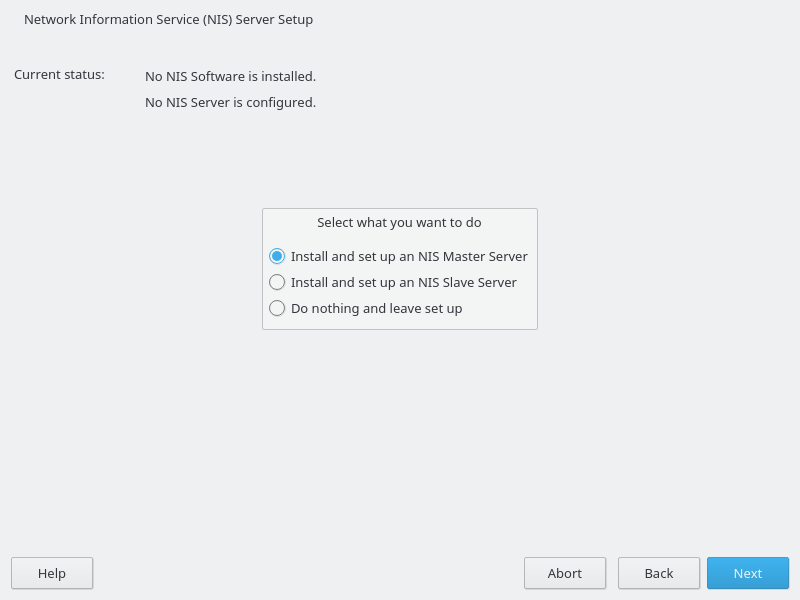

- 3.1 NIS server setup

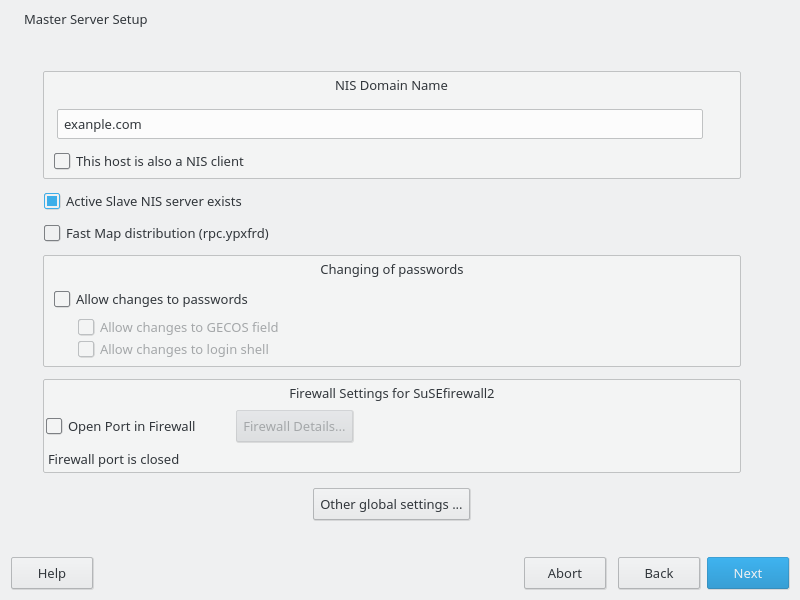

- 3.2 Master server setup

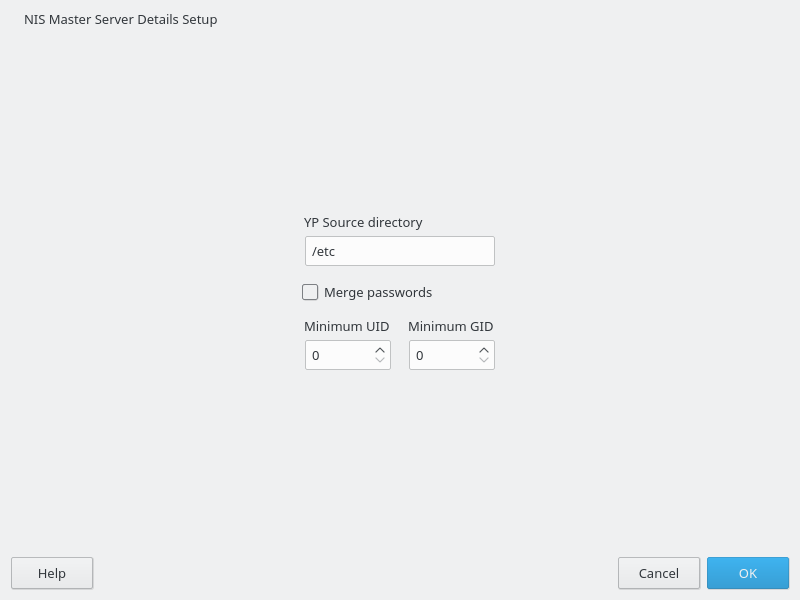

- 3.3 Changing the directory and synchronizing files for a NIS server

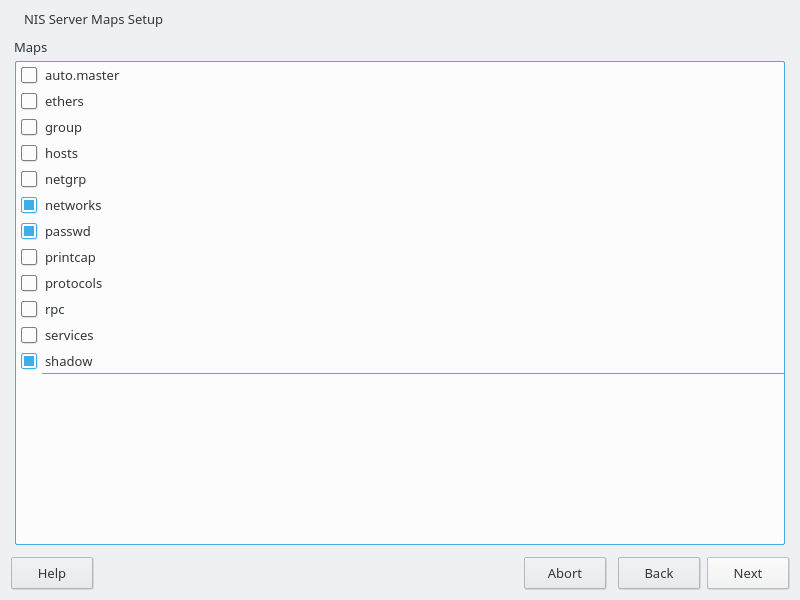

- 3.4 NIS server maps setup

- 3.5 Setting request permissions for a NIS server

- 3.6 Setting domain and address of a NIS server

- 5.1 Structure of an LDAP directory

- 6.1 Kerberos network topology

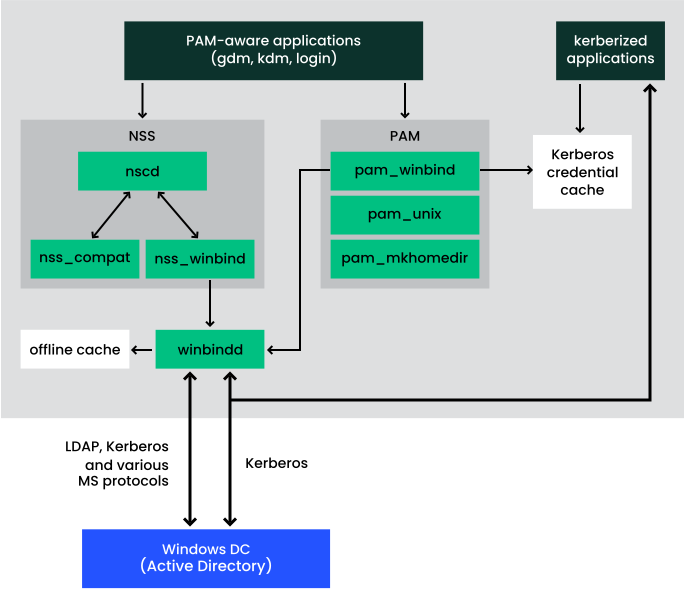

- 7.1 Schema of Winbind-based Active Directory authentication

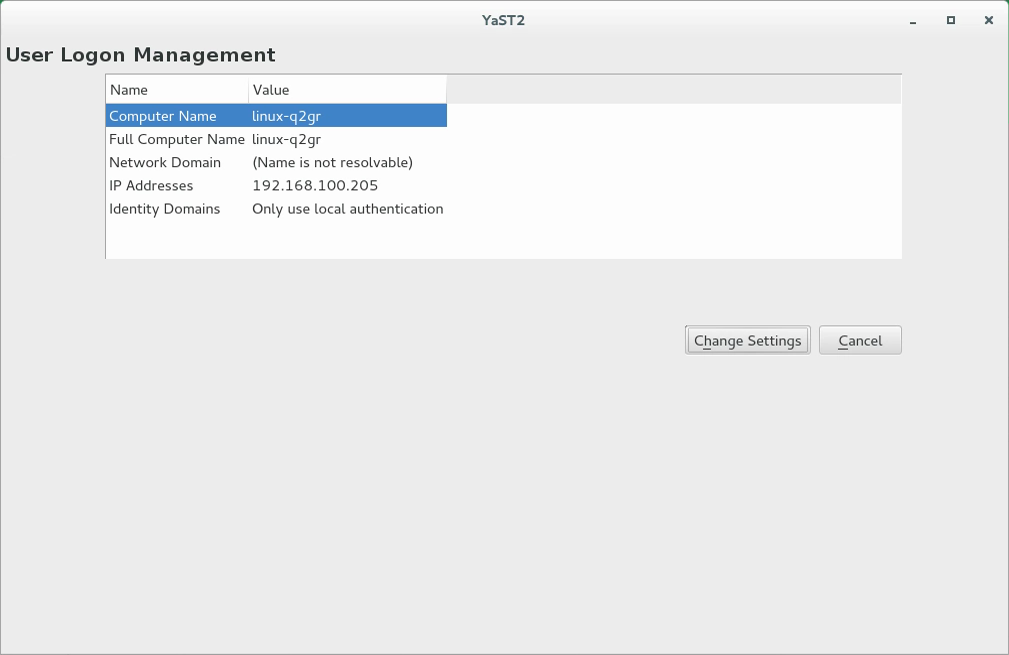

- 7.2 Main window of

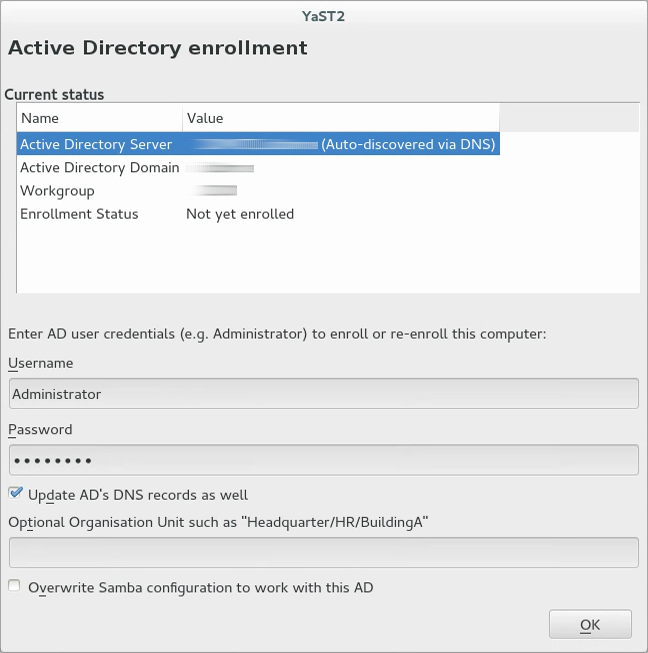

- 7.3 Enrolling into a domain

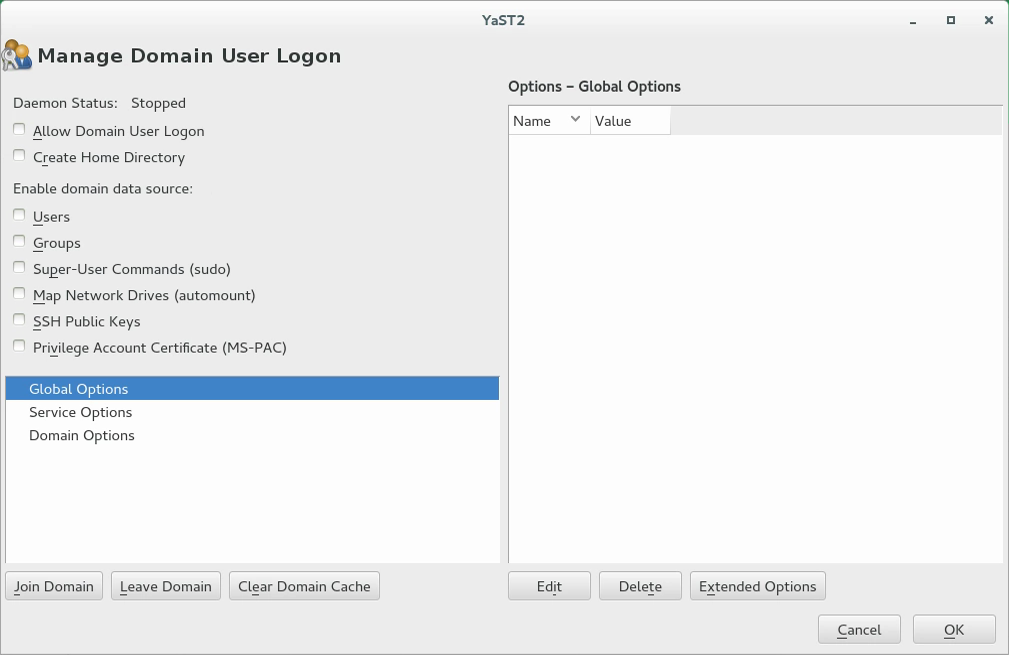

- 7.4 Configuration window of

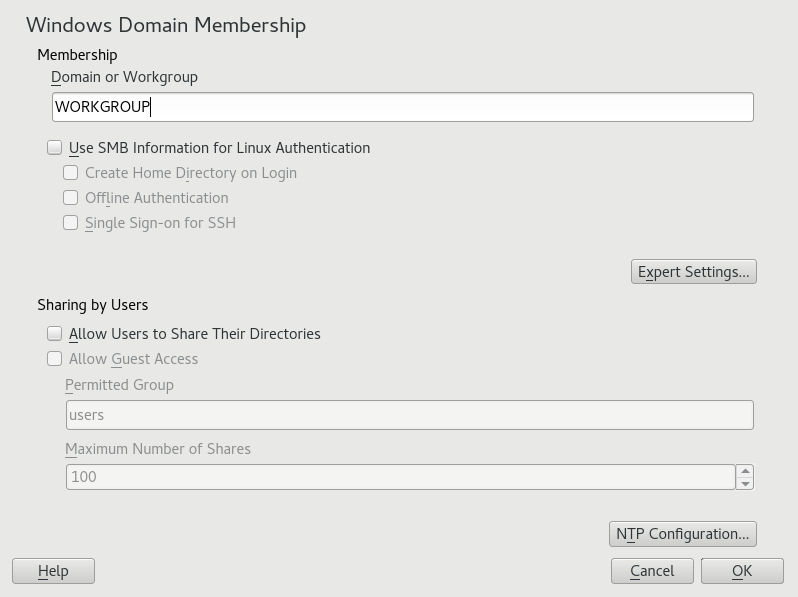

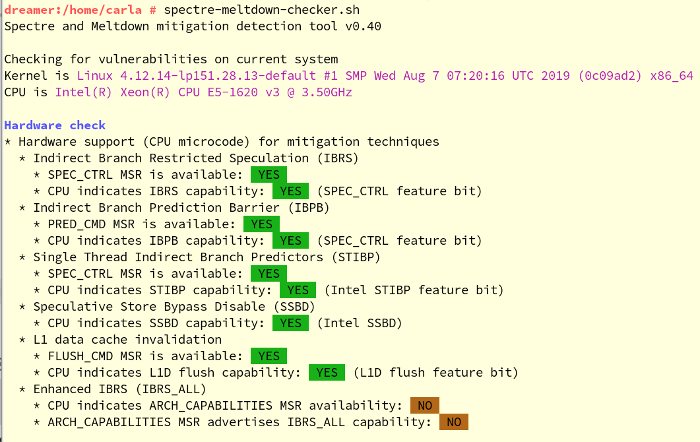

- 7.5 Determining Windows domain membership

- 7.6 Providing administrator credentials

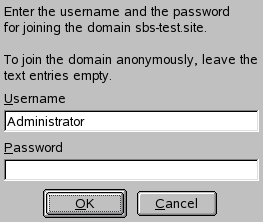

- 13.1 Key retrieval with

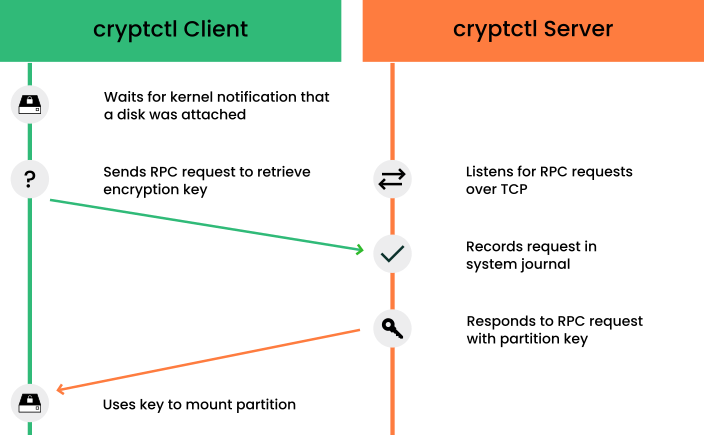

cryptctl(model without connection to KMIP server) - 16.1 Output from spectre-meltdown-checker

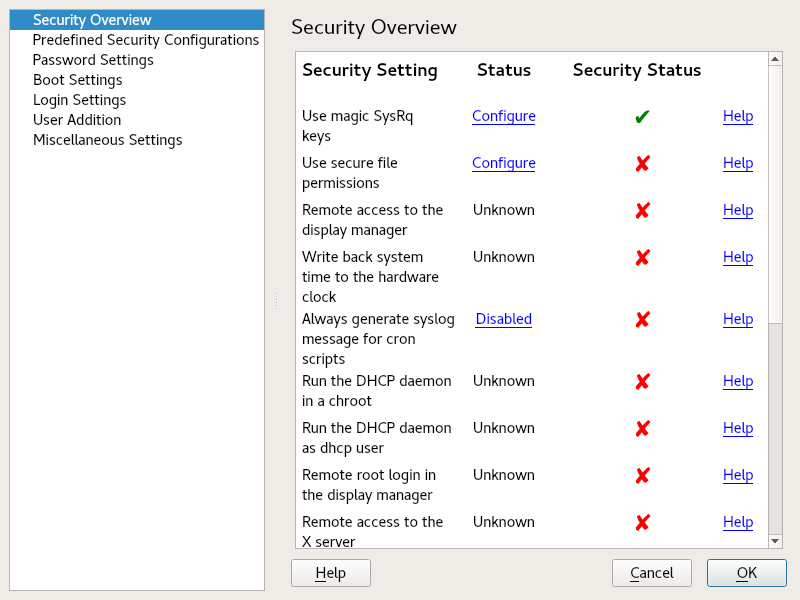

- 17.1 YaST security center and hardening: security overview

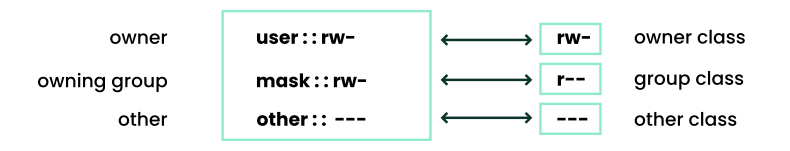

- 19.1 Minimum ACL: ACL entries compared to permission bits

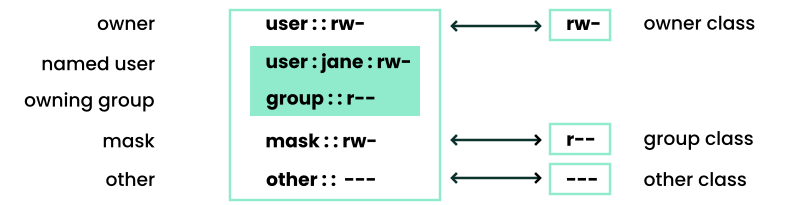

- 19.2 Extended ACL: ACL entries compared to permission bits

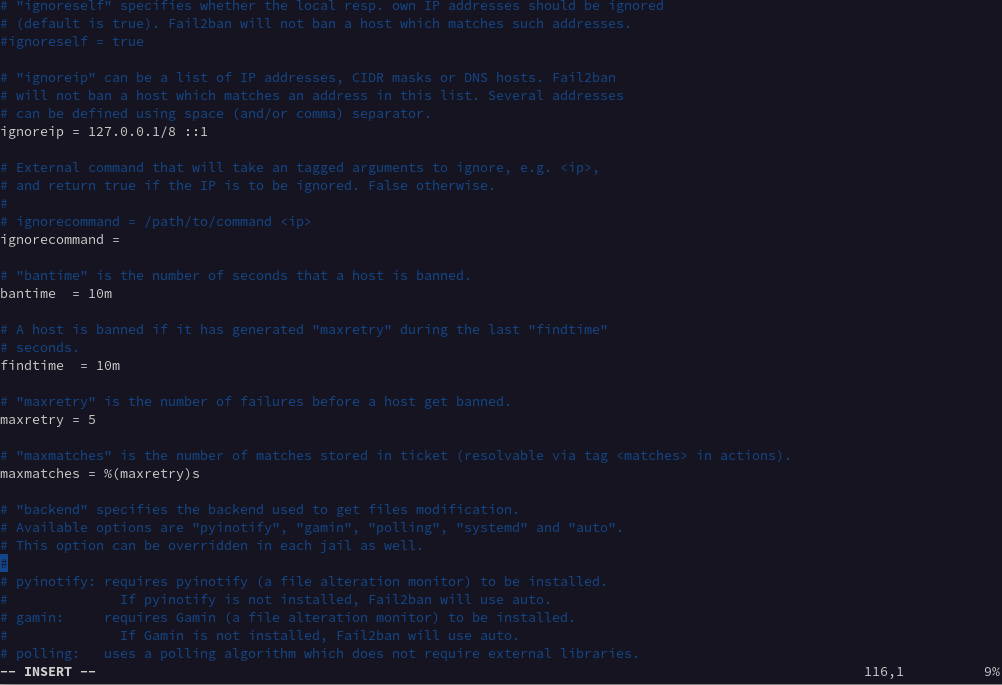

- 22.1 jail.local file settings

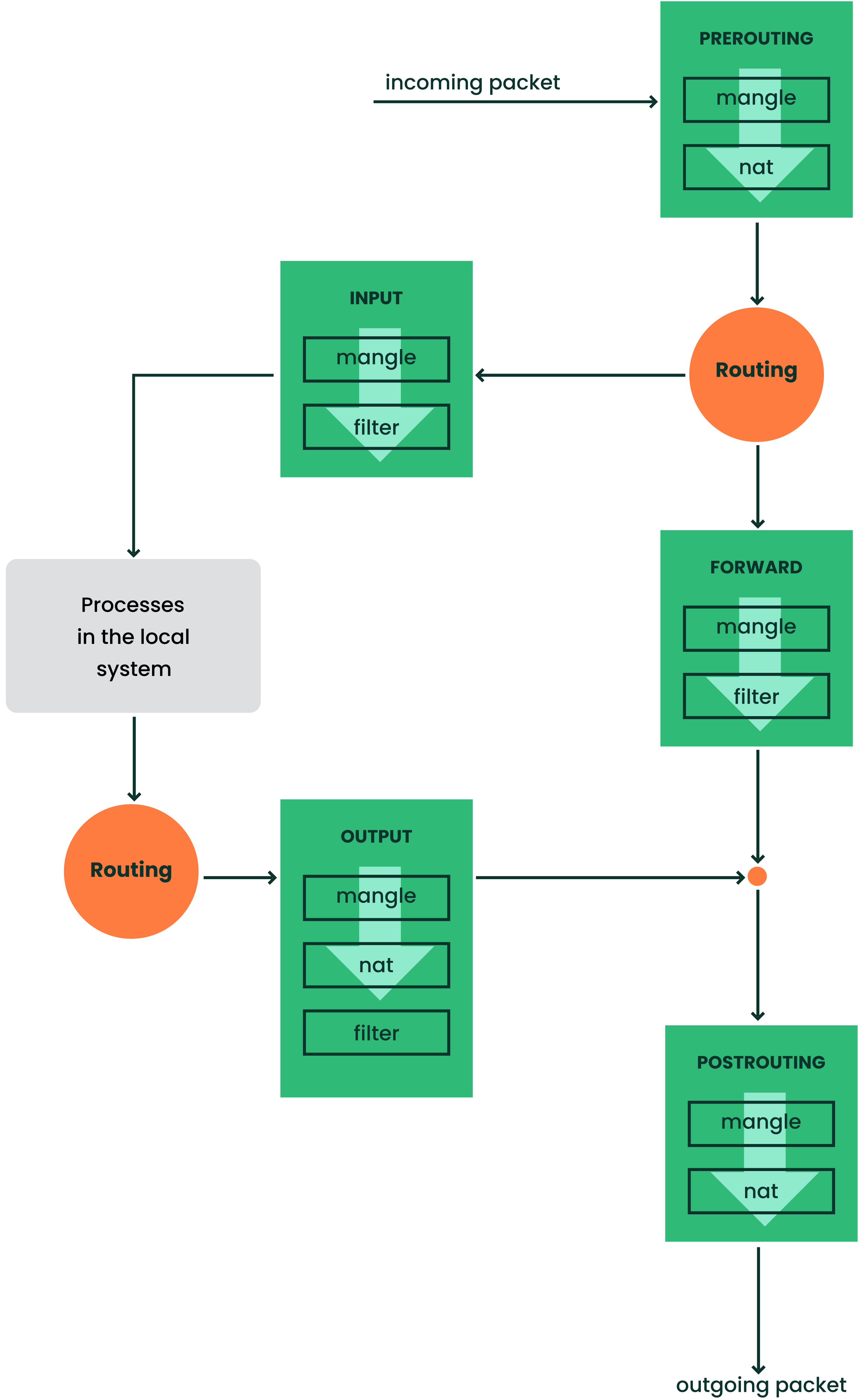

- 23.1 iptables: a packet's possible paths

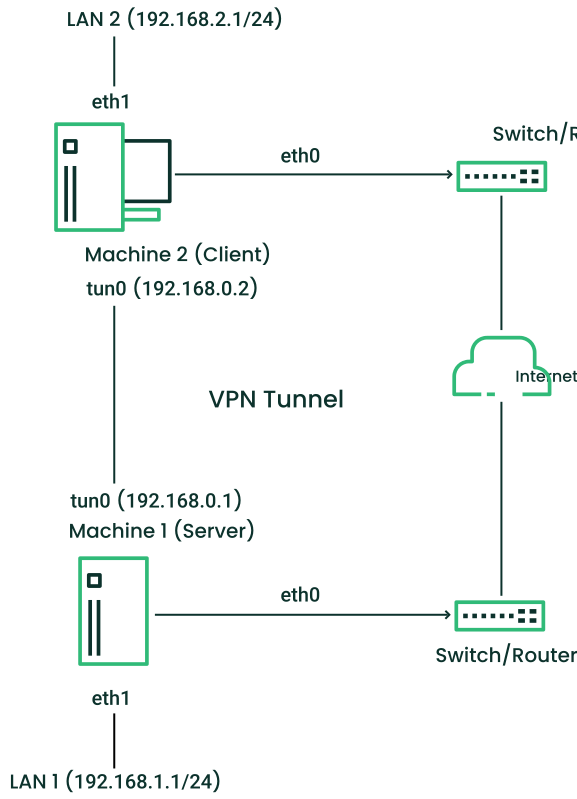

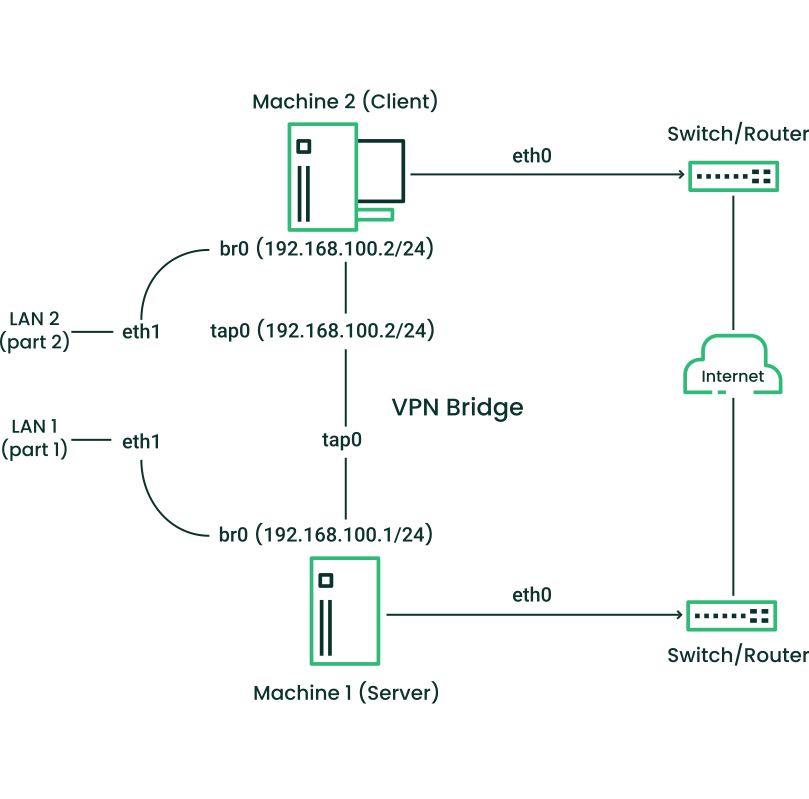

- 24.1 Routed VPN

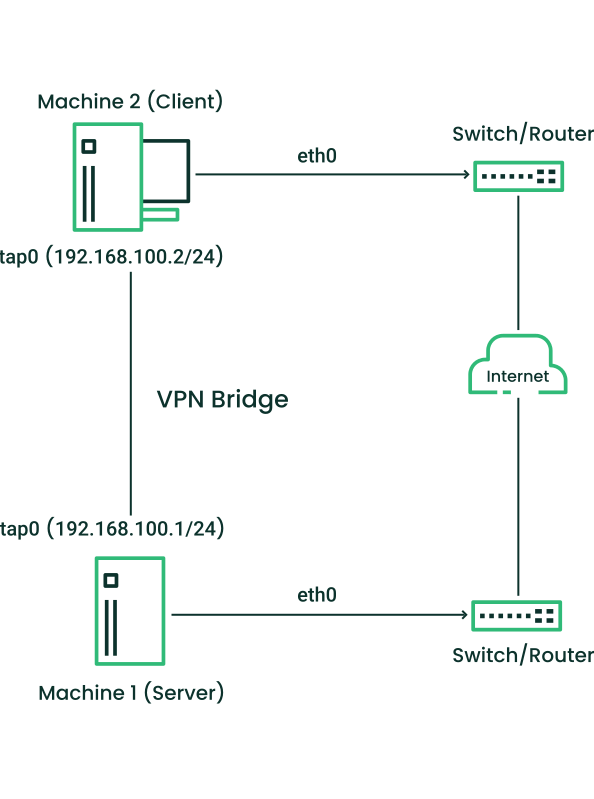

- 24.2 Bridged VPN - scenario 1

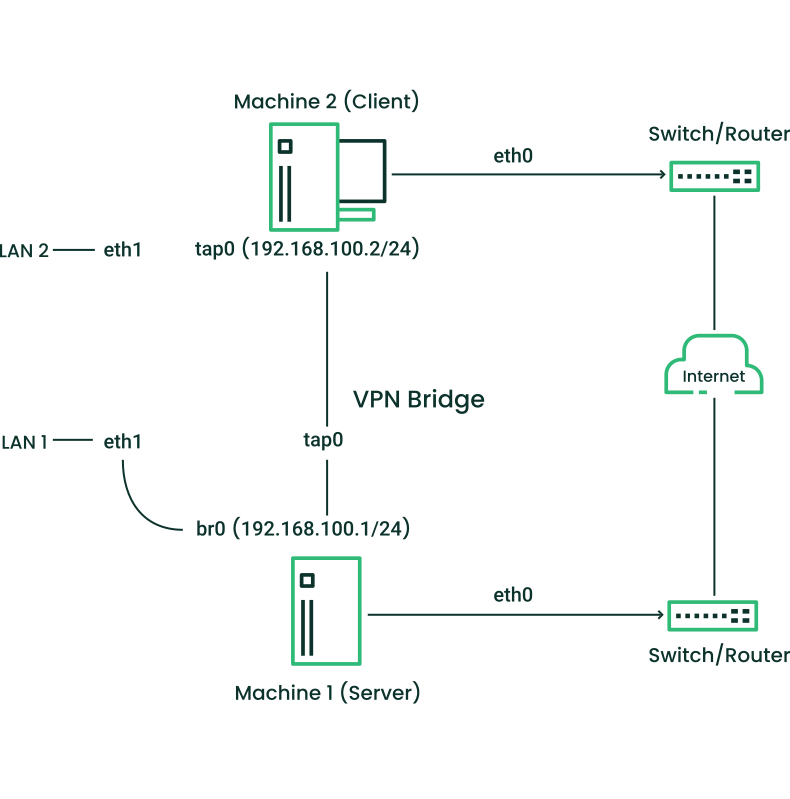

- 24.3 Bridged VPN - scenario 2

- 24.4 Bridged VPN - scenario 3

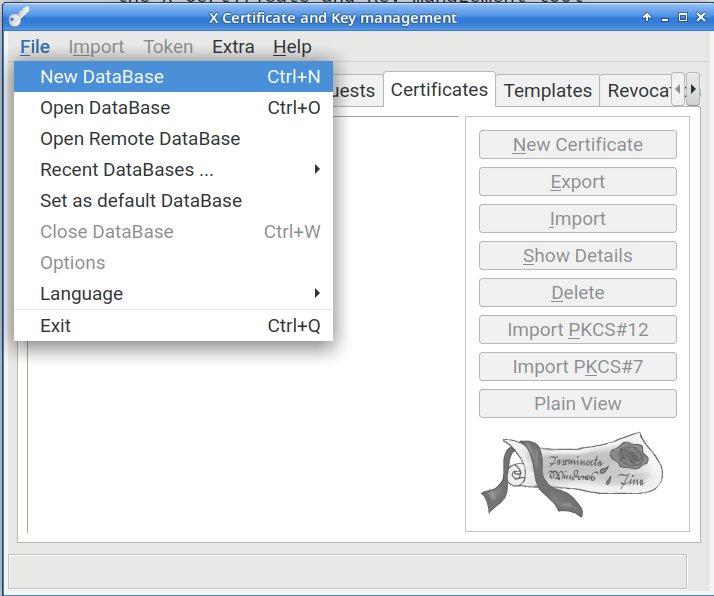

- 25.1 Create a new XCA database

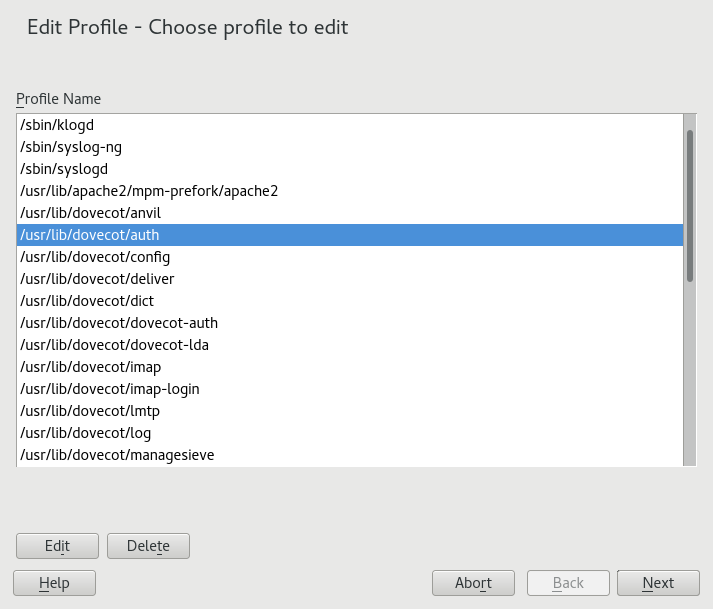

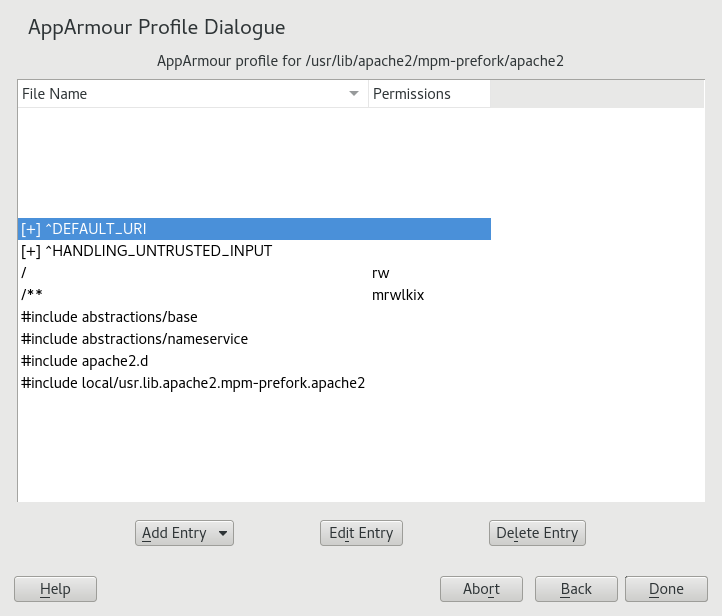

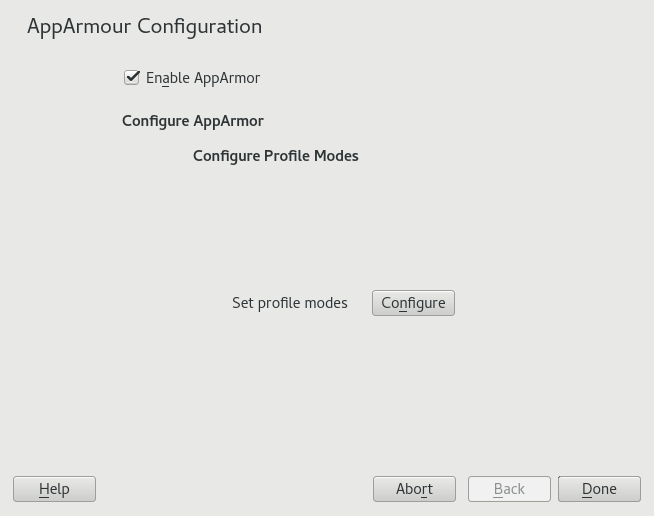

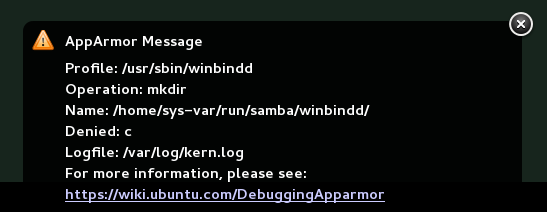

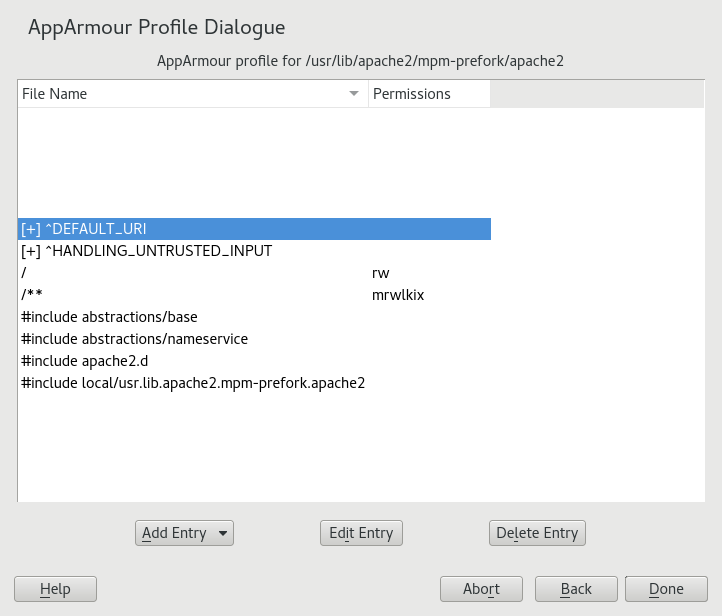

- 33.1

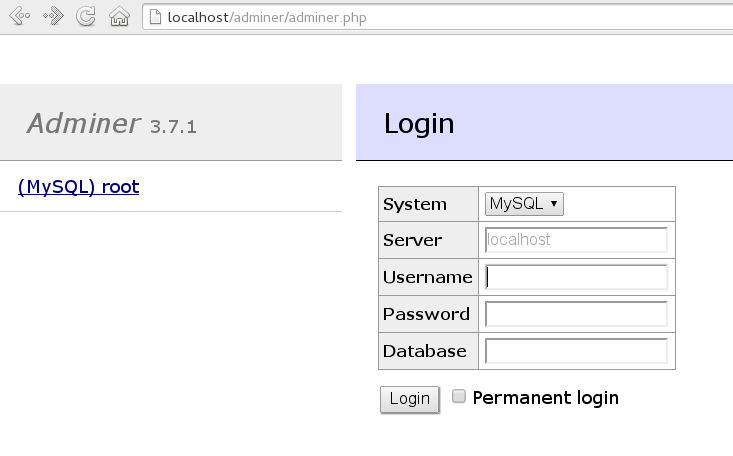

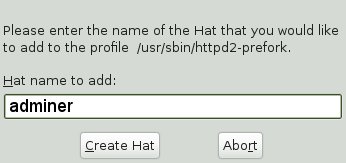

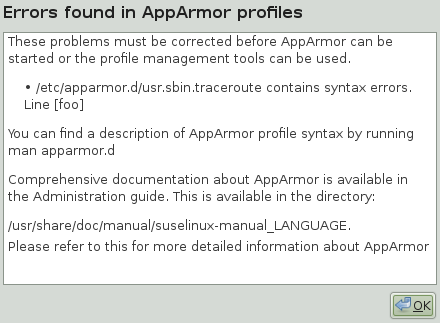

aa-notify Message in GNOME - 34.1 Adminer login page

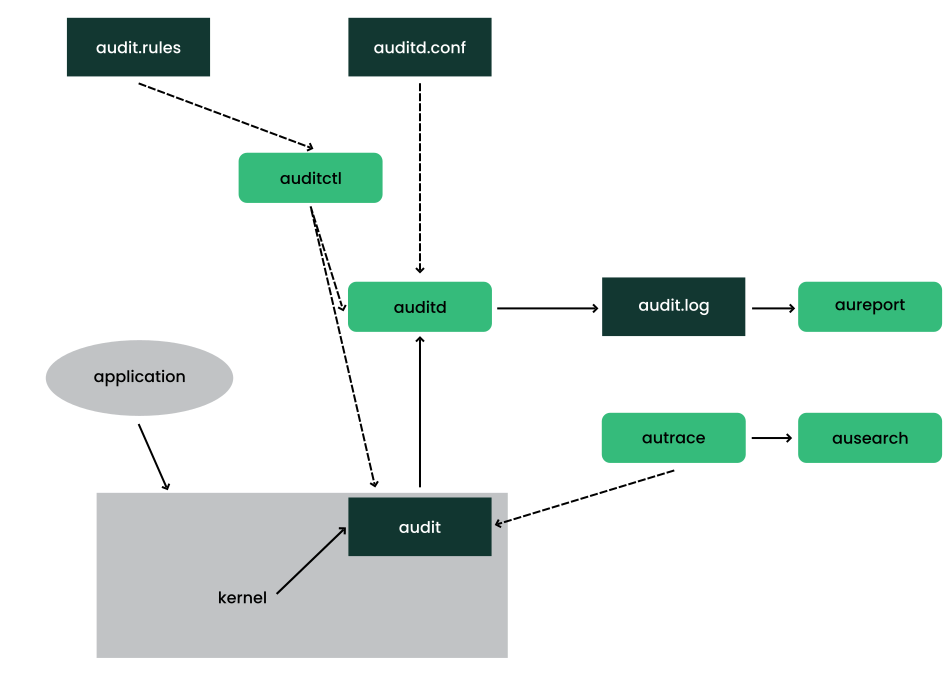

- 40.1 Introducing the components of Linux audit

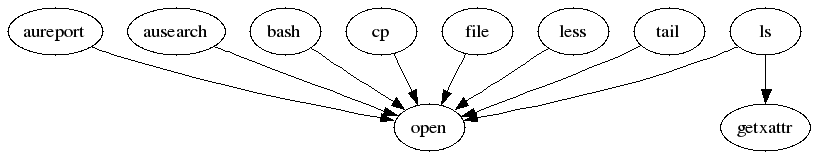

- 40.2 Flow graph—program versus system call relationship

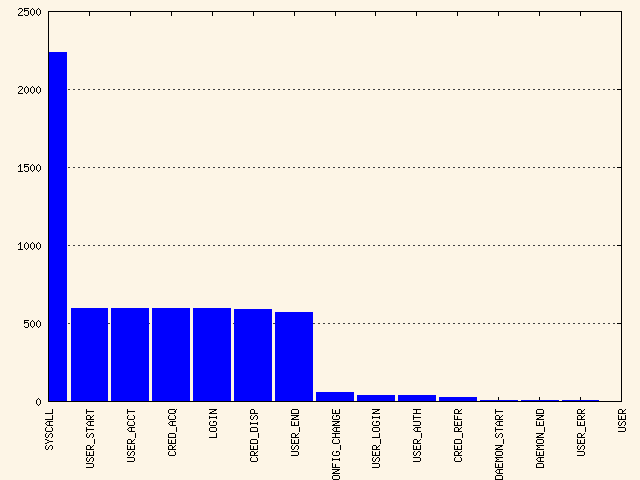

- 40.3 Bar chart—common event types

- 5.1 Commonly used object classes and attributes

- 13.1 List of all parameters to define the resource group with the cryptctl crm script.

- 14.1 Sample rules/constraints for password enforcement

- 19.1 ACL entry types

- 19.2 Masking access permissions

- 20.1 Important AIDE check boxes

- 23.1 Important sysconfig variables for static port configuration

- 37.1 Man pages: sections and categories

- 40.1 Audit status flags

- 2.1 PAM configuration for sshd (

/etc/pam.d/sshd) - 2.2 Default configuration for the

authsection (common-auth) - 2.3 Default configuration for the

accountsection (common-account) - 2.4 Default configuration for the

passwordsection (common-password) - 2.5 Default configuration for the

sessionsection (common-session) - 2.6 pam_env.conf

- 5.1 Excerpt from CN=schema

- 5.2 Minimal 389 Directory Server instance configuration file

- 5.3 A

.dsrcfile for local administration - 5.4 Two supplier replicas

- 5.5 Four supplier replicas

- 5.6 Six replicas

- 5.7 Six replicas with read-only consumers

- 6.1 Example KDC configuration,

/etc/krb5.conf - 9.1 Configuration

- 22.1 Example sshd_config

- 23.1 Callback port configuration for the

nfskernel module in/etc/modprobe.d/60-nfs.conf - 23.2 Commands to define a new

firewalldRPC service for NFS - 24.1 VPN server configuration file

- 24.2 VPN client configuration file

- 28.1 Output of

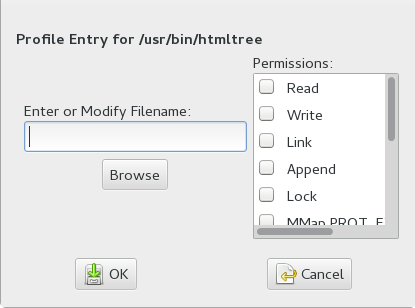

aa-unconfined - 33.1 Learning mode exception: controlling access to specific resources

- 33.2 Learning mode exception: defining permissions for an entry

- 39.1 Security context settings using

ls -Z - 39.2 Verifying that SELinux is functional

- 39.3 Getting a list of booleans and verifying policy access

- 39.4 Getting file context information

- 39.5 The default context for directories in the root directory

- 39.6 Showing SELinux settings for processes with

ps Zaux - 39.7 Viewing default file contexts

- 39.8 Example lines from

/var/log/audit/audit.log - 39.9 Analyzing audit messages

- 39.10 Viewing which lines deny access

- 39.11 Creating a policy module allowing an action previously denied

- 40.1 Default /etc/audit/auditd.conf

- 40.2 Example output of

auditctl-s - 40.3 Example audit rules—audit system parameters

- 40.4 Example audit rules—file system auditing

- 40.5 Example audit rules—system call auditing

- 40.6 Deleting audit rules and events

- 40.7 Listing rules with

auditctl-l - 40.8 A simple audit event—viewing the audit log

- 40.9 An advanced audit event—login via SSH

- 40.10 Example /etc/audit/auditd.conf

- 40.11 Example /etc/audit/plugins.d/syslog.conf

Copyright © 2006–2024 SUSE LLC and contributors. All rights reserved.

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or (at your option) version 1.3; with the Invariant Section being this copyright notice and license. A copy of the license version 1.2 is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”.

For SUSE trademarks, see https://www.suse.com/company/legal/. All third-party trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Trademark symbols (®, ™ etc.) denote trademarks of SUSE and its affiliates. Asterisks (*) denote third-party trademarks.

All information found in this book has been compiled with utmost attention to detail. However, this does not guarantee complete accuracy. Neither SUSE LLC, its affiliates, the authors nor the translators shall be held liable for possible errors or the consequences thereof.

Preface #Edit source

1 Available documentation #Edit source

- Online documentation

Our documentation is available online at https://doc.opensuse.org. Browse or download the documentation in various formats.

Note: Latest updates

The latest updates are usually available in the English-language version of this documentation.

- SUSE Knowledgebase

If you run into an issue, check out the Technical Information Documents (TIDs) that are available online at https://www.suse.com/support/kb/. Search the SUSE Knowledgebase for known solutions driven by customer need.

- In your system

For offline use, the release notes are also available under

/usr/share/doc/release-noteson your system. The documentation for individual packages is available at/usr/share/doc/packages.Many commands are also described in their manual pages. To view them, run

man, followed by a specific command name. If themancommand is not installed on your system, install it withsudo zypper install man.

2 Improving the documentation #Edit source

Your feedback and contributions to this documentation are welcome. The following channels for giving feedback are available:

- Bug reports

Report issues with the documentation at https://bugzilla.opensuse.org/.

To simplify this process, click the icon next to a headline in the HTML version of this document. This preselects the right product and category in Bugzilla and adds a link to the current section. You can start typing your bug report right away.

A Bugzilla account is required.

- Contributions

To contribute to this documentation, click the icon next to a headline in the HTML version of this document. This will take you to the source code on GitHub, where you can open a pull request.

A GitHub account is required.

Note: only available for English

The icons are only available for the English version of each document. For all other languages, use the icons instead.

For more information about the documentation environment used for this documentation, see the repository's README.

You can also report errors and send feedback concerning the documentation to <doc-team@suse.com>. Include the document title, the product version, and the publication date of the document. Additionally, include the relevant section number and title (or provide the URL) and provide a concise description of the problem.

- Help

If you need further help on openSUSE Leap, see https://en.opensuse.org/Portal:Support.

3 Documentation conventions #Edit source

The following notices and typographic conventions are used in this document:

/etc/passwd: Directory names and file namesPLACEHOLDER: Replace PLACEHOLDER with the actual value

PATH: An environment variablels,--help: Commands, options, and parametersuser: The name of a user or grouppackage_name: The name of a software package

Alt, Alt–F1: A key to press or a key combination. Keys are shown in uppercase as on a keyboard.

, › : menu items, buttons

Chapter 1, “Example chapter”: A cross-reference to another chapter in this guide.

Commands that must be run with

rootprivileges. You can also prefix these commands with thesudocommand to run them as a non-privileged user:#command>sudocommandCommands that can be run by non-privileged users:

>commandCommands can be split into two or multiple lines by a backslash character (

\) at the end of a line. The backslash informs the shell that the command invocation will continue after the end of the line:>echoa b \ c dA code block that shows both the command (preceded by a prompt) and the respective output returned by the shell:

>commandoutputNotices

Warning: Warning notice

Vital information you must be aware of before proceeding. Warns you about security issues, potential loss of data, damage to hardware, or physical hazards.

Important: Important notice

Important information you should be aware of before proceeding.

Note: Note notice

Additional information, for example about differences in software versions.

Tip: Tip notice

Helpful information, like a guideline or a piece of practical advice.

Compact Notices

Additional information, for example about differences in software versions.

Helpful information, like a guideline or a piece of practical advice.

1 Security and confidentiality #Edit source

Abstract#

This chapter introduces basic concepts of computer security. Threats and basic mitigation techniques are described. The chapter also provides references to other chapters, guides and Web sites with further information.

1.1 Overview #Edit source

One main characteristic of Linux is its ability to handle multiple users at the same time (multiuser) and to allow these users to simultaneously perform tasks (multitasking) on the same computer. To users, there is no difference between working with data stored locally and data stored in the network.

Because of the multiuser capability, data from different users has to be stored separately to guarantee security and privacy. Also important is the ability to keep data available in spite of a lost or damaged data medium, for example a hard disk.

This chapter is primarily focused on confidentiality and privacy. But a comprehensive security concept includes a regularly updated, workable, and tested backup. Without a backup, restoring data after it has been tampered with or after a hardware failure is hard.

Use a defense-in-depth approach to security: Assume that no single threat mitigation can fully protect your systems and data, but multiple layers of defense make an attack much harder. Components of a defense-in-depth strategy can be the following:

Hashing passwords (for example with PBKDF2, bcrypt, or scrypt) and salting them

Encrypting data (for example with AES)

Logging, monitoring, and intrusion detection

Firewall

Antivirus scanner

Defined and documented emergency procedures

Backups

Physical security

Audits, security scans, and intrusion tests

openSUSE Leap includes software that addresses the requirements of the list above. The following sections provide starting points for securing your system.

1.2 Passwords #Edit source

On a Linux system, only hashes of passwords are stored. Hashes are one-way algorithms which scramble data to a digital fingerprint that is hard to reverse.

The hashes are stored in the file /etc/shadow,

which cannot be read by normal users. Because restoring passwords is

possible with powerful computers, hashed passwords should not be

visible to regular users.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) publishes a guideline for passwords, which is available at https://pages.nist.gov/800-63-3/sp800-63b.html#sec5

For details about how to set a password policy, see Section 17.3, “”. For general information about authentication on Linux, see Part I, “Authentication”.

1.3 Backups #Edit source

If your system is compromised, backups can be used to restore a prior system state. When bugs or accidents occur, backups can also be used to compare the current system against an older version. For production systems, it is important to take some backups off-site for cases like disasters (for example, off-site storage of tapes/recordable media, or off-site initiated).

For legal reasons, some firms and organizations must be careful about backing up too much information and holding it too long. If your environment has a policy regarding the destruction of old paper files, you might need to extend this policy to Linux backup tapes as well.

The rules about physical security of servers apply to backups as well. Additionally, it is advisable to encrypt backup data. This can be done either per individual backup archive or for the complete backup file system, if applicable. Should a backup medium ever be lost, for example during transportation, the data is protected against unauthorized access. The same applies if a backup system itself is compromised. To some extent encryption also ensures the integrity of the backups. Keep in mind, however, that the appropriate people need to be able to decrypt backups in emergency situations. Also, the case that an encryption key itself is compromised and needs to be replaced should be considered.

If a system is known to be compromised or suspected to be compromised, then it is vital to determine the integrity status of backups. If a system compromise went undetected for a long period of time, then it is possible that backups already include manipulated configuration files or malicious programs. Keeping a long enough history of backups allows to inspect for possible unwarranted differences.

Even without any known security breach, a regular inspection of differences among important configuration files in backups can help with finding security issues (maybe even accidental misconfigurations). This approach is best suited for files and environments where the content does not change too frequently.

1.4 System integrity #Edit source

If it is possible to physically access a computer, the firmware and boot process can be manipulated to gain access when an authorized person boots the machine. While not all computers can be locked into inaccessible rooms, your first step should be physically locking the server room.

Also remember that disposing of old equipment must be handled in a secure manner. Securing the boot loader and restricting removable media also provide useful physical security. See Chapter 9, Physical security for more information.

Consider taking the following additional measures:

Configure your system so it cannot be booted from a removable device.

Protect the boot process with a UEFI password, Secure Boot, and a GRUB2 password.

Linux systems are started by a boot loader that allows passing additional options to the booted kernel. You can prevent others from using such parameters during boot by setting an additional password for the boot loader. This is crucial to system security. Not only does the kernel itself run with

rootpermissions, but it is also the first authority to grantrootpermissions at system start-up.For more information about setting a password in the boot loader, see Book “Reference”, Chapter 12 “The boot loader GRUB 2”, Section 12.2.6 “Setting a boot password”.

Enable hard disk encryption. For more information, see Chapter 12, Encrypting partitions and files.

Use

cryptctlto encrypt hosted storage. For more information, see Chapter 13, Storage encryption for hosted applications with cryptctl.Use AIDE to detect any changes in your system configuration. For more information, see Chapter 20, Intrusion detection with AIDE.

1.5 File access #Edit source

Because of the everything is a file approach in

Linux, file permissions are important for controlling access to most

resources. This means that by using file permissions, you can define

access to regular files, directories and hardware devices.

By default, most hardware devices are only accessible for

root. However, certain devices, for example serial ports, can be

accessible for normal users.

As a general rule, always work with the most restrictive privileges

possible for a given task. For example, it is definitely not

necessary to be root to read or write e-mail. If the mail

program has a bug, this bug could be exploited for an attack that

acts with exactly the permissions of the program at the time of the

attack. By following the above rule, minimize the possible damage.

For details, see Section 19.1, “Traditional file permissions” and Section 19.2, “Advantages of ACLs”.

AppArmor and SELinux allow you to set constraints for applications and users. For details, see Part IV, “Confining privileges with AppArmor” and Part V, “SELinux”.

If there is a chance that hard disks could be accessed outside of the installed operating system, for example by booting a live system or removing the hardware, encrypt the data. openSUSE Leap allows you to encrypt partitions containing data and the operating system. For details, see Chapter 12, Encrypting partitions and files.

1.6 Networking #Edit source

Securing network services is a crucial task. Aim to secure as many layers of the OSI model as possible.

All communication should be authenticated and encrypted with up-to-date cryptographic algorithms on the transport or application layer. Use a Virtual Private Network (VPN) as an additional secure layer on physical networks.

openSUSE Leap provides many options for securing your network:

Use

opensslto create X509 certificates. These certificates can be used for encryption and authentication of many services. You can set up your own certificate authority (CA) and use it as a source of trust in your network. For details, seeman openssl.At least parts of networks are exposed to the public Internet. Reduce attack surfaces by closing ports with firewall rules and by uninstalling or at least disabling services that are not required. For details, see Chapter 23, Masquerading and firewalls.

Use OpenVPN to secure communication channels over insecure physical networks. For details, see Chapter 24, Configuring a VPN server.

Use strong authentication for network services. For details, see Part I, “Authentication”.

1.7 Software vulnerabilities #Edit source

Software vulnerabilities are issues in software that can be exploited to obtain unauthorized access or misuse systems. Vulnerabilities are especially critical if they affect remote services, such as HTTP servers. Computer systems are complex, therefore they always include certain vulnerabilities.

When such issues become known, they must be fixed in the software by software developers. The resulting update must then be installed by system administrators in a timely and safe manner on affected systems.

Vulnerabilities are announced on centralized databases, for example the National Vulnerability Database, which is maintained by the US government. You can subscribe to feeds to stay informed about newly discovered vulnerabilities. In some cases the problems induced by the bugs can be mitigated until a software update is provided. Vulnerabilities are assigned a Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) number and a Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) score. The score helps identify the severity of vulnerabilities.

SUSE provides a feed of security advisories. It is available at https://www.suse.com/en-us/support/update/. There is also a list of security updates by CVE number available at https://www.suse.com/support/security/.

Administrators should be prepared for severe vulnerabilities in their systems. This includes hardening all computers as far as possible. Also, we recommend to have predefined procedures in place for quickly installing updates for severe vulnerabilities.

To reduce the damage of possible attacks, use restrictive file permissions. See Section 19.1, “Traditional file permissions”.

Other useful links:

http://lists.opensuse.org/opensuse-security-announce/, mailing list with openSUSE security announcements

https://nvd.nist.gov/, the National Vulnerability Database

https://cve.mitre.org/, MITRE's CVE database

https://www.bsi.bund.de/SiteGlobals/Forms/Suche/BSI/Sicherheitswarnungen/Sicherheitswarnungen_Formular.html, German Federal Office for Information Security vulnerability feed

https://www.first.org/cvss/, information about the Common Vulnerability Scoring System

1.8 Malware #Edit source

Malware is software that is intended to interrupt the normal functioning of a computer or steal data. This includes viruses, worms, ransomware or rootkits. Sometimes malware uses software vulnerabilities to attack a computer. However, often it is accidentally executed by a user, especially when installing third-party software from unknown sources. openSUSE Leap provides an extensive list of programs (packages) in its download repositories. This reduces the need to download third-party software. All packages provided by SUSE are signed. The package manager of openSUSE Leap checks the signatures of packages after the download to verify their integrity.

The command rpm --checksig

RPM_FILE shows whether the

checksum and the signature of a package are correct.

You can find the signing key on the first DVD of openSUSE Leap and

on most key servers worldwide.

You can use the ClamAV antivirus software to detect malware on your system. ClamAV can be integrated into several services, for example mail servers and HTTP proxies. This can be used to filter malware before it reaches the user.

Restrictive user privileges can reduce the risk of accidental code execution.

1.9 Important security tips #Edit source

The following tips are a quick summary of the sections above:

Stay informed about the latest security issues. Get and install the updated packages recommended by security announcements as quickly as possible.

Avoid using

rootprivileges whenever possible. Set restrictive file permissions.Only use encrypted protocols for network communication.

Disable any network services you do not absolutely require.

Conduct regular security audits. For example, scan your network for open ports.

Monitor the integrity of files on your systems with

AIDE(Advanced Intrusion Detection Environment).Take proper care when installing any third-party software.

Check all your backups regularly.

Check your log files, for example, with Logwatch.

Configure the firewall to block all ports that are not explicitly whitelisted.

Design your security measures to be redundant.

Use encryption where possible, for example, for hard disks of mobile. computers.

1.10 Reporting security issues #Edit source

If you discover a security-related problem, first check the available update packages. If no update is available, write an e-mail to <security@suse.de>. Include a detailed description of the problem and the version number of the package concerned. We encourage you to encrypt e-mails with GPG.

You can find a current version of the SUSE GPG key at https://www.suse.com/support/security/contact/.

Part I Authentication #Edit source

- 2 Authentication with PAM

Linux uses PAM (pluggable authentication modules) in the authentication process as a layer that mediates between user and application. PAM modules are available on a system-wide basis, so they can be requested by any application. This chapter describes how the modular authentication mechanism works and how it is configured.

- 3 Using NIS

When multiple Unix systems in a network access common resources, it becomes imperative that all user and group identities are the same for all machines in that network. The network should be transparent to users: their environments should not vary, regardless of which machine they are using. This can be done by NIS and NFS services.

NIS (Network Information Service) can be described as a database-like service that provides access to the contents of

/etc/passwd,/etc/shadow, and/etc/groupacross networks. NIS can also be used for other purposes (making the contents of files like/etc/hostsor/etc/servicesavailable, for example), but this is beyond the scope of this introduction. People often refer to NIS as YP, because it works like the network's “yellow pages.”- 4 Setting up authentication clients using YaST

Whereas Kerberos is used for authentication, LDAP is used for authorization and identification. Both can work together. For more information about LDAP, see Chapter 5, LDAP with 389 Directory Server, and about Kerberos, see Chapter 6, Network authentication with Kerberos.

- 5 LDAP with 389 Directory Server

The Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) is a protocol designed to access and maintain information directories. LDAP can be used for tasks such as user and group management, system configuration management, and address management. In openSUSE Leap 15.6 the LDAP service is provided by the 389 Directory Server, replacing OpenLDAP.

- 6 Network authentication with Kerberos

Kerberos is a network authentication protocol which also provides encryption. This chapter describes how to set up Kerberos and integrate services like LDAP and NFS.

- 7 Active Directory support

Active Directory* (AD) is a directory-service based on LDAP, Kerberos, and other services. It is used by Microsoft* Windows* to manage resources, services, and people. In a Microsoft Windows network, Active Directory provides information about these objects, restricts access to them, and enforces po…

- 8 Setting up a freeRADIUS server

The RADIUS (Remote Authentication Dial-In User Service) protocol has long been a standard service for manage network access. It provides authentication, authorization and accounting (AAA) for large businesses such as Internet service providers and cellular network providers, and is also popular for …

2 Authentication with PAM #Edit source

Abstract#

Linux uses PAM (pluggable authentication modules) in the authentication process as a layer that mediates between user and application. PAM modules are available on a system-wide basis, so they can be requested by any application. This chapter describes how the modular authentication mechanism works and how it is configured.

2.1 What is PAM? #Edit source

System administrators and programmers often want to restrict access to certain parts of the system or to limit the use of certain functions of an application. Without PAM, applications must be adapted every time a new authentication mechanism, such as LDAP, Samba, or Kerberos, is introduced. However, this process is time-consuming and error-prone. One way to avoid these drawbacks is to separate applications from the authentication mechanism and delegate authentication to centrally managed modules. Whenever a newly required authentication scheme is needed, it is sufficient to adapt or write a suitable PAM module for use by the program in question.

The PAM concept consists of:

PAM modules, which are a set of shared libraries for a specific authentication mechanism.

A module stack with of one or more PAM modules.

A PAM-aware service which needs authentication by using a module stack or PAM modules. Usually a service is a familiar name of the corresponding application, like

loginorsu. The service nameotheris a reserved word for default rules.Module arguments, with which the execution of a single PAM module can be influenced.

A mechanism evaluating each result of a single PAM module execution. A positive value executes the next PAM module. The way a negative value is dealt with depends on the configuration: “no influence, proceed” up to “terminate immediately” and anything in between are valid options.

2.2 Structure of a PAM configuration file #Edit source

PAM can be configured in two ways:

- File based configuration (

/etc/pam.conf) The configuration of each service is stored in

/etc/pam.conf. However, for maintenance and usability reasons, this configuration scheme is not used in openSUSE Leap.- Directory based configuration (

/etc/pam.d/) Every service (or program) that relies on the PAM mechanism has its own configuration file in the

/etc/pam.d/directory. For example, the service forsshdcan be found in the/etc/pam.d/sshdfile.

The files under /etc/pam.d/ define the PAM modules

used for authentication. Each file consists of lines, which define a

service, and each line consists of a maximum of four components:

TYPE CONTROL MODULE_PATH MODULE_ARGS

The components have the following meaning:

- TYPE

Declares the type of the service. PAM modules are processed as stacks. Different types of modules have different purposes. For example, one module checks the password, another verifies the location from which the system is accessed, and yet another reads user-specific settings. PAM knows about four different types of modules:

authCheck the user's authenticity, traditionally by querying a password. However, this can also be achieved with a chip card or through biometrics (for example, fingerprints or iris scan).

accountModules of this type check if the user has general permission to use the requested service. As an example, such a check should be performed to ensure that no one can log in with the user name of an expired account.

passwordThe purpose of this type of module is to enable the change of an authentication token. Usually this is a password.

sessionModules of this type are responsible for managing and configuring user sessions. They are started before and after authentication to log login attempts and configure the user's specific environment (mail accounts, home directory, system limits, etc.).

- CONTROL

Indicates the behavior of a PAM module. Each module can have the following control flags:

requiredA module with this flag must be successfully processed before the authentication may proceed. After the failure of a module with the

requiredflag, all other modules with the same flag are processed before the user receives a message about the failure of the authentication attempt.requisiteModules having this flag must also be processed successfully, in much the same way as a module with the

requiredflag. However, in case of failure a module with this flag gives immediate feedback to the user and no further modules are processed. In case of success, other modules are subsequently processed, like any modules with therequiredflag. Therequisiteflag can be used as a basic filter checking for the existence of certain conditions that are essential for a correct authentication.sufficientAfter a module with this flag has been successfully processed, the requesting application receives an immediate message about the success and no further modules are processed, provided there was no preceding failure of a module with the

requiredflag. The failure of a module with thesufficientflag has no direct consequences, in the sense that any subsequent modules are processed in their respective order.optionalThe failure or success of a module with this flag does not have any direct consequences. This can be useful for modules that are only intended to display a message (for example, to tell the user that mail has arrived) without taking any further action.

includeIf this flag is given, the file specified as argument is inserted at this place.

- MODULE_PATH

Contains a full file name of a PAM module. It does not need to be specified explicitly, if the module is located in the default directory

/lib/security(for all 64-bit platforms supported by openSUSE® Leap, the directory is/lib64/security).- MODULE_ARGS

Contains a space-separated list of options to influence the behavior of a PAM module, such as

debug(enables debugging) ornullok(allows the use of empty passwords).

In addition, there are global configuration files for PAM modules under

/etc/security, which define the exact behavior of

these modules (examples include pam_env.conf and

time.conf). Every application that uses a PAM module

calls a set of PAM functions, which then process the information

in the configuration files and return the result to the

requesting application.

To simplify the creation and maintenance of PAM modules, common default

configuration files for the types auth,

account, password, and

session modules have been introduced. These are

retrieved from every application's PAM configuration. Updates to the

global PAM configuration modules in common-* are

thus propagated across all PAM configuration files without requiring the

administrator to update every single PAM configuration file.

The global PAM configuration files are maintained using the

pam-config tool. This tool automatically adds new

modules to the configuration, changes the configuration of existing ones

or deletes modules (or options) from the configurations. Manual

intervention in maintaining PAM configurations is minimized or no longer

required.

Note: 64-bit and 32-bit mixed installations

When using a 64-bit operating system, it is possible to also include a runtime environment for 32-bit applications. In this case, make sure that you also install the 32-bit version of the PAM modules.

2.3 The PAM configuration of sshd #Edit source

Consider the PAM configuration of sshd as an example:

Example 2.1: PAM configuration for sshd (/etc/pam.d/sshd) #

#%PAM-1.0 1 auth requisite pam_nologin.so 2 auth include common-auth 3 account requisite pam_nologin.so 2 account include common-account 3 password include common-password 3 session required pam_loginuid.so 4 session include common-session 3 session optional pam_lastlog.so silent noupdate showfailed 5

Declares the version of this configuration file for PAM 1.0. This is merely a convention, but could be used in the future to check the version. | |

Checks, if | |

Refers to the configuration files of four module types:

| |

Sets the login UID process attribute for the process that was authenticated. | |

Displays information about the last login of a user. |

By including the configuration files instead of adding each module separately to the respective PAM configuration, you automatically get an updated PAM configuration when an administrator changes the defaults. Formerly, you needed to adjust all configuration files manually for all applications when changes to PAM occurred or a new application was installed. Now the PAM configuration is made with central configuration files and all changes are automatically inherited by the PAM configuration of each service.

The first include file (common-auth) calls three

modules of the auth type:

pam_env.so,

pam_gnome_keyring.so and

pam_unix.so. See

Example 2.2, “Default configuration for the auth section (common-auth)”.

Example 2.2: Default configuration for the auth section (common-auth) #

auth required pam_env.so 1 auth optional pam_gnome_keyring.so 2 auth required pam_unix.so try_first_pass 3

| |

| |

|

The whole stack of auth modules is processed before

sshd gets any feedback about

whether the login has succeeded. All modules of the stack having the

required control flag must be processed successfully

before sshd receives a message

about the positive result. If one of the modules is not successful, the

entire module stack is still processed and only then is

sshd notified about the negative

result.

When all modules of the auth type have been

successfully processed, another include statement is processed, in this

case, that in Example 2.3, “Default configuration for the account section (common-account)”.

common-account contains only one module,

pam_unix. If pam_unix returns the

result that the user exists, sshd receives a message announcing this

success and the next stack of modules (password) is

processed, shown in Example 2.4, “Default configuration for the password section (common-password)”.

Example 2.3: Default configuration for the account section (common-account) #

account required pam_unix.so try_first_pass

Example 2.4: Default configuration for the password section (common-password) #

password requisite pam_cracklib.so password optional pam_gnome_keyring.so use_authtok password required pam_unix.so use_authtok nullok shadow try_first_pass

Again, the PAM configuration of

sshd involves only an include

statement referring to the default configuration for

password modules located in

common-password. These modules must successfully be

completed (control flags requisite and

required) whenever the application requests the change

of an authentication token.

Changing a password or another authentication token requires a security

check. This is achieved with the pam_cracklib

module. The pam_unix module used afterward carries

over any old and new passwords from pam_cracklib, so

the user does not need to authenticate again after changing the password.

This procedure makes it impossible to circumvent the checks carried out

by pam_cracklib. Whenever the

account or the auth type are

configured to complain about expired passwords, the

password modules should also be used.

Example 2.5: Default configuration for the session section (common-session) #

session required pam_limits.so session required pam_unix.so try_first_pass session optional pam_umask.so session optional pam_systemd.so session optional pam_gnome_keyring.so auto_start only_if=gdm,gdm-password,lxdm,lightdm session optional pam_env.so

As the final step, the modules of the session type

(bundled in the common-session file) are called to

configure the session according to the settings for the user in question.

The pam_limits module loads the file

/etc/security/limits.conf, which may define limits

on the use of certain system resources. The pam_unix

module is processed again. The pam_umask module can

be used to set the file mode creation mask. Since this module carries the

optional flag, a failure of this module would not

affect the successful completion of the entire session module stack. The

session modules are called a second time when the user

logs out.

2.4 Configuration of PAM modules #Edit source

Some PAM modules are configurable. The configuration files are

located in /etc/security. This section briefly

describes the configuration files relevant to the sshd

example—pam_env.conf and

limits.conf.

2.4.1 pam_env.conf #Edit source

pam_env.conf can be used to define a standardized

environment for users that is set whenever the

pam_env module is called. With it, preset

environment variables using the following syntax:

VARIABLE [DEFAULT=VALUE] [OVERRIDE=VALUE]

- VARIABLE

Name of the environment variable to set.

[DEFAULT=<value>]Default VALUE the administrator wants to set.

[OVERRIDE=<value>]Values that may be queried and set by

pam_env, overriding the default value.

A typical example of how pam_env can be used is

the adaptation of the DISPLAY variable, which is changed

whenever a remote login takes place. This is shown in

Example 2.6, “pam_env.conf”.

Example 2.6: pam_env.conf #

REMOTEHOST DEFAULT=localhost OVERRIDE=@{PAM_RHOST}

DISPLAY DEFAULT=${REMOTEHOST}:0.0 OVERRIDE=${DISPLAY}

The first line sets the value of the REMOTEHOST variable

to localhost, which is used whenever

pam_env cannot determine any other value. The

DISPLAY variable in turn contains the value of

REMOTEHOST. Find more information in the comments in

/etc/security/pam_env.conf.

2.4.2 pam_mount.conf.xml #Edit source

The purpose of pam_mount is to mount user home

directories during the login process, and to unmount them during logout

in an environment where a central file server keeps all the home

directories of users. With this method, it is not necessary to mount a

complete /home directory where all the user home

directories would be accessible. Instead, only the home directory of the

user who is about to log in, is mounted.

After installing pam_mount, a template for

pam_mount.conf.xml is available in

/etc/security. The description of the

elements can be found in the manual page man 5

pam_mount.conf.

A basic configuration of this feature can be done with YaST. Select › › to add the file server.

2.4.3 limits.conf #Edit source

System limits can be set on a user or group basis in

limits.conf, which is read by the

pam_limits module. The file allows you to set

hard limits, which may not be exceeded, and soft limits, which

may be exceeded temporarily. For more information about the syntax and

the options, see the comments in

/etc/security/limits.conf.

2.5 Configuring PAM using pam-config #Edit source

The pam-config tool helps you configure the global PAM

configuration files (/etc/pam.d/common-*) and

several selected application configurations. For a list of supported

modules, use the pam-config --list-modules command.

Use the pam-config command to maintain your PAM

configuration files. Add new modules to your PAM configurations, delete

other modules or modify options to these modules. When changing global

PAM configuration files, no manual tweaking of the PAM setup for

individual applications is required.

A simple use case for pam-config involves the

following:

Auto-generate a fresh unix-style PAM configuration. Let pam-config create the simplest possible setup which you can extend later on. The

pam-config --createcommand creates a simple Unix authentication configuration. Pre-existing configuration files not maintained by pam-config are overwritten, but backup copies are kept as*.pam-config-backup.Add a new authentication method. Adding a new authentication method (for example, SSSD) to your stack of PAM modules comes down to a simple

pam-config --add --ssscommand. SSSD is added wherever appropriate across allcommon-*-pcPAM configuration files.Add debugging for test purposes. To make sure the new authentication procedure works as planned, turn on debugging for all PAM-related operations. The

pam-config --add --sss-debugcommand turns on debugging for SSSD-related PAM operations. Find the debugging output in thesystemdjournal (see Book “Reference”, Chapter 11 “journalctl: query thesystemdjournal”).Query your setup. Before you finally apply your new PAM setup, check if it contains all the options you wanted to add. The

pam-config --query --MODULE command lists both the type and the options for the queried PAM module.Remove the debug options. Finally, remove the debug option from your setup when you are entirely satisfied with its performance. The

pam-config --delete --sss-debugcommand turns off debugging for thepam_ssh.somodule. In case you had debugging options added for other modules, use similar commands to turn these off.

For more information on the pam-config command and the

options available, refer to the manual page of

pam-config(8).

2.6 Manually configuring PAM #Edit source

If you prefer to manually create or maintain your PAM configuration

files, make sure to disable pam-config for these

files.

When you create your PAM configuration files from scratch using the

pam-config --create command, it creates symbolic links

from the common-* to the

common-*-pc files.

pam-config only modifies the

common-*-pc configuration

files. Removing these symbolic links effectively disables pam-config,

because pam-config only operates on the

common-*-pc files and

these files are not put into effect without the symbolic links.

Warning: Include pam_systemd.so in configuration

If you are creating your own PAM configuration, make sure to include

pam_systemd.so configured as session

optional. Not including the pam_systemd.so can

cause problems with systemd task limits. For details, refer to the man

page of pam_systemd.so.

2.7 Configuring U2F keys for local login #Edit source

To provide more security during the local login , you can configure

two-factor authentication using the pam-u2f framework and

the U2F feature on YubiKeys and Security Keys.

To set up U2F on your system, you need to associate your key with your account . After that, configure your system to use the key. The procedure is described in the following sections.

2.7.1 Associating the U2F key with your account #Edit source

To associate your U2F key with your account, proceed as follows:

Log in to your machine.

Insert your U2F key.

Create a directory for the U2F key configuration:

>sudomkdir -p ~/.config/YubicoRun the

pamu2fcfgcommand that outputs configuration lines:>sudopamu2fcfg > ~/.config/Yubico/u2f_keysWhen your device begins flashing, touch the metal contact to confirm the association.

We recommend using a backup U2F device, which you can set up by running the following commands:

Run:

>sudopamu2fcfg -n >> ~/.config/Yubico/u2f_keysWhen your device begins flashing, touch the metal contact to confirm the association.

You can move the output file from the default location to a directory that

requires the sudo permission to modify the file to

increase security. For example, move it to the /etc

directory.

To do so, follow the steps:

Create a directory in

/etc:>sudomkdir /etc/YubicoMove the created file:

>sudomv ~/.config/Yubico/u2f_keys /etc/Yubico/u2f_keys

Note: Placing the u2f_keys to a non-default location

If you move the output file to a different directory than is the default

($HOME/.config/Yubico/u2f_keys), you need to add the

path to the /etc/pam.d/login file as described in

Section 2.7.2, “Updating the PAM configuration”.

2.7.2 Updating the PAM configuration #Edit source

After you have created the U2F keys configuration, you need to adjust the PAM configuration on your system.

Open the file

/etc/pam.d/login.Add the line

auth required pam_u2f.soto the file as follows:#%PAM-1.0 auth include common-auth auth required pam_u2f.so account include common-account password include common-password session optional pam_keyinit.so revoke session include common-session #session optional pam_xauth.soIf you placed the

u2f_keysfile to a different location than$HOME/.config/Yubico/u2f_keys, you need to use theauthfileoption in the/etc/pam.d/loginPAM file as follows:#%PAM-1.0 auth requisite pam_nologin.so auth include common-auth auth required pam_u2f.so authfile=<PATH_TO_u2f_keys> ...where <PATH_TO_u2f_keys> is the absolute path to the

u2f_keysfile.

2.8 More information #Edit source

In the /usr/share/doc/packages/pam directory after

installing the pam-doc package, find the

following additional documentation:

- READMEs

In the top level of this directory, there is the

modulessubdirectory holding README files about the available PAM modules.- The Linux-PAM System Administrators' Guide

This document comprises everything that the system administrator should know about PAM. It discusses a range of topics, from the syntax of configuration files to the security aspects of PAM.

- The Linux-PAM Module Writers' Manual

This document summarizes the topic from the developer's point of view, with information about how to write standard-compliant PAM modules.

- The Linux-PAM Application Developers' Guide

This document comprises everything needed by an application developer who wants to use the PAM libraries.

- The PAM manual pages

PAM and the individual modules come with manual pages that provide a good overview of the functionality of all the components.

3 Using NIS #Edit source

Abstract#

When multiple Unix systems in a network access common resources, it becomes imperative that all user and group identities are the same for all machines in that network. The network should be transparent to users: their environments should not vary, regardless of which machine they are using. This can be done by NIS and NFS services.

NIS (Network Information Service) can be described as a database-like

service that provides access to the contents of

/etc/passwd, /etc/shadow, and

/etc/group across networks. NIS can also be used

for other purposes (making the contents of files like

/etc/hosts or /etc/services

available, for example), but this is beyond the scope of this

introduction. People often refer to NIS as YP,

because it works like the network's “yellow pages.”

3.1 Configuring NIS servers #Edit source

To distribute NIS information across networks, either install one single server (a master) that serves all clients, or NIS slave servers requesting this information from the master and relaying it to their respective clients.

To configure just one NIS server for your network, proceed with Section 3.1.1, “Configuring a NIS master server”.

If your NIS master server needs to export its data to slave servers, set up the master server as described in Section 3.1.1, “Configuring a NIS master server” and set up slave servers in the subnets as described in Section 3.1.2, “Configuring a NIS slave server”.

3.1.1 Configuring a NIS master server #Edit source

To manage the NIS Server functionality with YaST, install the yast2-nis-server package by running the zypper in yast2-nis-server command as root. To configure a NIS master server for your network, proceed as follows:

Start › › .

If you need just one NIS server in your network or if this server is to act as the master for further NIS slave servers, select . YaST installs the required packages.

Tip: Already installed NIS server software

If NIS server software is already installed on your machine, initiate the creation of a NIS master server by clicking .

Figure 3.1: NIS server setup #

Determine basic NIS setup options:

Enter the NIS domain name.

Define whether the host should also be a NIS client (enabling users to log in and access data from the NIS server) by selecting .

If your NIS server needs to act as a master server to NIS slave servers in other subnets, select .

The option is only useful with . It speeds up the transfer of maps to the slaves.

Select to allow users in your network (both local users and those managed through the NIS server) to change their passwords on the NIS server (with the command

yppasswd). This makes the options and available. “GECOS” means that the users can also change their names and address settings with the commandypchfn. “Shell” allows users to change their default shell with the commandypchsh(for example, to switch from Bash to sh). The new shell must be one of the predefined entries in/etc/shells.Select to have YaST adapt the firewall settings for the NIS server.

Figure 3.2: Master server setup #

Leave this dialog with or click to make additional settings.

include changing the source directory of the NIS server (

/etcby default). In addition, passwords can be merged here. The setting should be to create the user database from the system authentication files/etc/passwd,/etc/shadowand/etc/group. Also, determine the smallest user and group ID that should be offered by NIS. Click to confirm your settings and return to the previous screen.Figure 3.3: Changing the directory and synchronizing files for a NIS server #

If you previously enabled , enter the host names used as slaves and click . If no slave servers exist, this configuration step is skipped.

Continue to the dialog for the database configuration. Specify the NIS Server Maps, the partial databases to transfer from the NIS server to the client. The default settings are adequate. Leave this dialog with .

Check which maps should be available and click to continue.

Figure 3.4: NIS server maps setup #

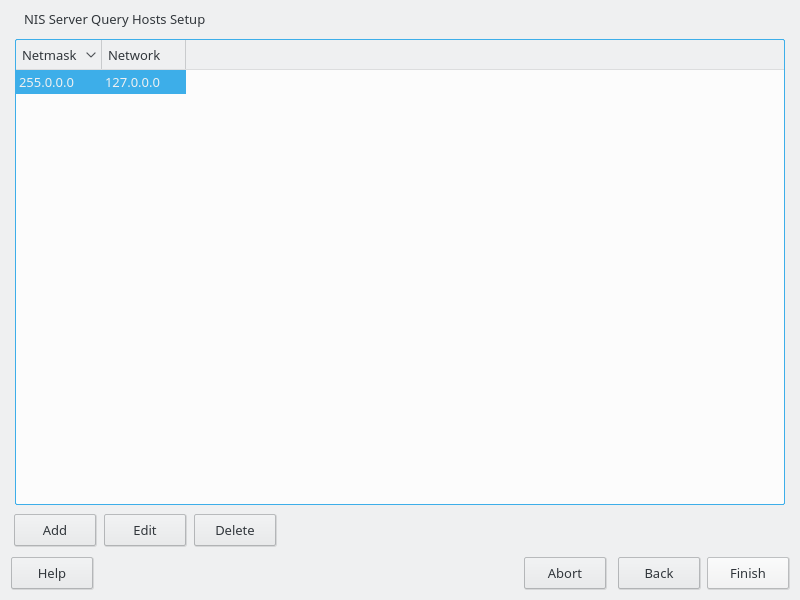

Determine which hosts are allowed to query the NIS server. You can add, edit, or delete hosts by clicking the appropriate button. Specify from which networks requests can be sent to the NIS server. Normally, this is your internal network. In this case, there should be the following two entries:

255.0.0.0 127.0.0.0 0.0.0.0 0.0.0.0

The first entry enables connections from your own host, which is the NIS server. The second one allows all hosts to send requests to the server.

Figure 3.5: Setting request permissions for a NIS server #

Click to save your changes and exit the setup.

3.1.2 Configuring a NIS slave server #Edit source

To configure additional NIS slave servers in your network, proceed as follows:

Start › › .

Select and click .

Tip

If NIS server software is already installed on your machine, initiate the creation of a NIS slave server by clicking .

Complete the basic setup of your NIS slave server:

Enter the NIS domain.

Enter host name or IP address of the master server.

Set to enable user logins on this server.

Adapt the firewall settings with .

Click .

Enter the hosts that are allowed to query the NIS server. You can add, edit, or delete hosts by clicking the appropriate button. Specify all networks from which requests can be sent to the NIS server. If it applies to all networks, use the following configuration:

255.0.0.0 127.0.0.0 0.0.0.0 0.0.0.0

The first entry enables connections from your own host, which is the NIS server. The second one allows all hosts with access to the same network to send requests to the server.

Click to save changes and exit the setup.

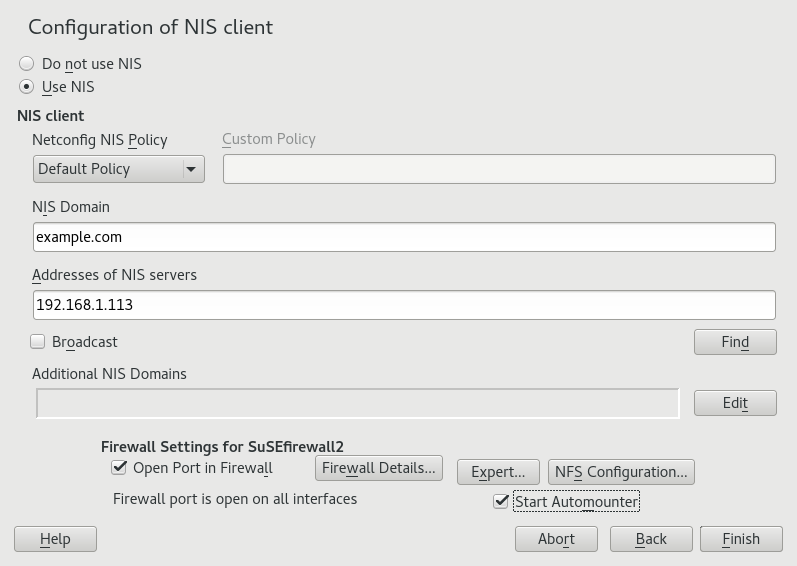

3.2 Configuring NIS clients #Edit source

To use NIS on a workstation, do the following:

Start › › .

Activate the button.

Enter the NIS domain. This is a domain name given by your administrator or a static external IP address received by DHCP. For information about DHCP, see Book “Reference”, Chapter 20 “DHCP”.

Figure 3.6: Setting domain and address of a NIS server #

Enter your NIS servers and separate their addresses by spaces. If you do not know your NIS server, click to let YaST search for any NIS servers in your domain. Depending on the size of your local network, this may be a time-consuming process. asks for a NIS server in the local network after the specified servers fail to respond.

Depending on your local installation, you may also want to activate the automounter. This option also installs additional software if required.

If you do not want other hosts to be able to query which server your client is using, go to the settings and disable . By checking , the client is enabled to receive replies from a server communicating through an unprivileged port. For further information, see

manypbind.Click to save them and return to the YaST control center. Your client is now configured with NIS.

4 Setting up authentication clients using YaST #Edit source

Abstract#

Whereas Kerberos is used for authentication, LDAP is used for authorization and identification. Both can work together. For more information about LDAP, see Chapter 5, LDAP with 389 Directory Server, and about Kerberos, see Chapter 6, Network authentication with Kerberos.

4.1 Configuring an authentication client with YaST #Edit source

YaST allows setting up authentication to clients using different modules:

. Use both an identity service (usually LDAP) and a user authentication service (usually Kerberos). This option is based on SSSD and in the majority of cases is best suited for joining Active Directory domains.

This module is described in Section 7.3.2, “Joining Active Directory using ”.

. Join an Active Directory (which entails use of Kerberos and LDAP). This option is based on

winbindand is best suited for joining an Active Directory domain if support for NTLM or cross-forest trusts is necessary.This module is described in Section 7.3.3, “Joining Active Directory using ”.

4.2 SSSD #Edit source

Two of the YaST modules are based on SSSD: and .

SSSD stands for System Security Services Daemon. SSSD talks to remote directory services that provide user data and provides authentication methods, such as LDAP, Kerberos, or Active Directory (AD). It also provides an NSS (Name Service Switch) and PAM (Pluggable Authentication Module) interface.

SSSD can locally cache user data and then allow users to use the data, even if the real directory service is (temporarily) unreachable.

4.2.1 Checking the status #Edit source

After running one of the YaST authentication modules, you can check whether SSSD is running with:

#systemctl status sssdsssd.service - System Security Services Daemon Loaded: loaded (/usr/lib/systemd/system/sssd.service; enabled) Active: active (running) since Thu 2015-10-23 11:03:43 CEST; 5s ago [...]

4.2.2 Caching #Edit source

To allow logging in when the authentication back-end is unavailable, SSSD uses its cache even if it was invalidated. This happens until the back-end is available again.

To invalidate the cache, run sss_cache -E (the

command sss_cache is part of the package

sssd-tools).

To remove the SSSD cache, run:

>sudosystemctl stop sssd>sudorm -f /var/lib/sss/db/*>sudosystemctl start sssd

5 LDAP with 389 Directory Server #Edit source

Abstract#

The Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) is a protocol designed to access and maintain information directories. LDAP can be used for tasks such as user and group management, system configuration management, and address management. In openSUSE Leap 15.6 the LDAP service is provided by the 389 Directory Server, replacing OpenLDAP.

- 5.1 Structure of an LDAP directory tree

- 5.2 Creating and managing a Docker container for 389 Directory Server

- 5.3 Installing 389 Directory Server

- 5.4 Firewall configuration

- 5.5 Backing up and restoring 389 Directory Server

- 5.6 Managing LDAP users and groups

- 5.7 Managing plug-ins

- 5.8 Using SSSD to manage LDAP authentication

- 5.9 Migrating to 389 Directory Server from OpenLDAP

- 5.10 Importing TLS server certificates and keys

- 5.11 Setting up replication

- 5.12 Synchronizing with Microsoft Active Directory

- 5.13 More information

Ideally, a central server stores the data in a directory and distributes it to all clients using a well-defined protocol. The structured data allow a wide range of applications to access them. A central repository reduces the necessary administrative effort. The use of an open and standardized protocol such as LDAP ensures that as many client applications as possible can access such information.

A directory in this context is a type of database optimized for quick and effective reading and searching. The type of data stored in a directory tends to be long lived and changes infrequently. This allows the LDAP service to be optimized for high performance concurrent reads, whereas conventional databases are optimized for accepting many writes to data in a short time.

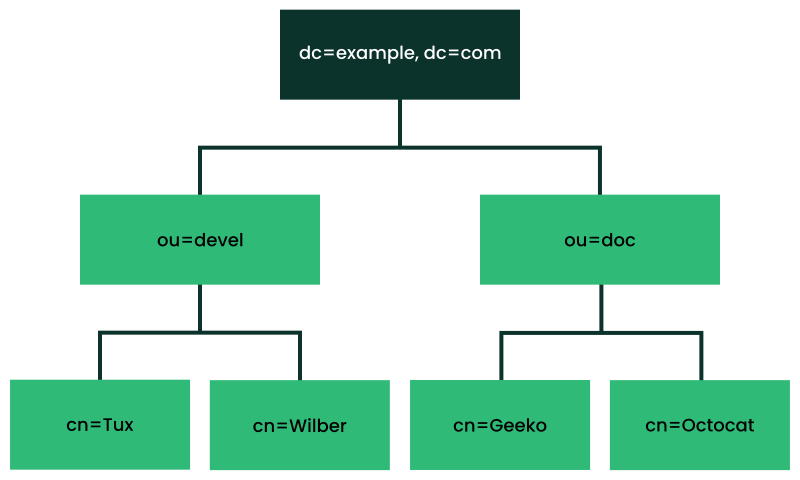

Structure of an LDAP directory tree #Edit source

This section introduces the layout of an LDAP directory tree, and provides the basic terminology used with regard to LDAP. If you are familiar with LDAP, read on at Section 5.3.1, “Setting up a new 389 Directory Server instance”.

An LDAP directory has a tree structure. All entries (called objects) of the directory have a defined position within this hierarchy. This hierarchy is called the directory information tree (DIT). The complete path to the desired entry, which unambiguously identifies it, is called the distinguished name or DN. An object in the tree is identified by its relative distinguished name (RDN). The distinguished name is built from the RDNs of all entries on the path to the entry.

The relations within an LDAP directory tree become more evident in the following example, shown in Figure 5.1, “Structure of an LDAP directory”.

Figure 5.1: Structure of an LDAP directory #

The complete diagram is a fictional directory information tree. The

entries on three levels are depicted. Each entry corresponds to one box

in the image. The complete, valid distinguished name

for the fictional employee Geeko

Linux, in this case, is cn=Geeko

Linux,ou=doc,dc=example,dc=com. It is composed by adding the

RDN cn=Geeko Linux to the DN of the preceding entry

ou=doc,dc=example,dc=com.

The types of objects that can be stored in the DIT are globally determined following a Schema. The type of an object is determined by the object class. The object class determines what attributes the relevant object must or may be assigned. The Schema contains all object classes and attributes which can be used by the LDAP server. Attributes are a structured data type. Their syntax, ordering and other behavior is defined by the Schema. LDAP servers supply a core set of Schemas which can work in a broad variety of environments. If a custom Schema is required, you can upload it to an LDAP server.

Table 5.1, “Commonly used object classes and attributes” offers a small overview of the object

classes from 00core.ldif and

06inetorgperson.ldif used in the example, including

required attributes (Req. Attr.) and valid attribute values. After installing

389 Directory Server, these can be found in

/usr/share/dirsrv/schema.

Table 5.1: Commonly used object classes and attributes #

|

Object Class |

Meaning |

Example Entry |

Req. Attr. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

name components of the domain |

example |

displayName |

|

|

organizational unit |

|

|

|

|

person-related data for the intranet or Internet |

|

|

Example 5.1, “Excerpt from CN=schema” shows an excerpt from a Schema directive with explanations.

Example 5.1: Excerpt from CN=schema #

attributetype (1.2.840.113556.1.2.102 NAME 'memberOf' 1 DESC 'Group that the entry belongs to' 2 SYNTAX 1.3.6.1.4.1.1466.115.121.1.12 3 X-ORIGIN 'Netscape Delegated Administrator') 4 objectclass (2.16.840.1.113730.3.2.333 NAME 'nsPerson' 5 DESC 'A representation of a person in a directory server' 6 SUP top STRUCTURAL 7 MUST ( displayName $ cn ) 8 MAY ( userPassword $ seeAlso $ description $ legalName $ mail \ $ preferredLanguage ) 9 X-ORIGIN '389 Directory Server Project' ...

The name of the attribute, its unique object identifier (OID, numerical), and the abbreviation of the attribute. | |

A brief description of the attribute with | |

The type of data that can be held in the attribute. In this case, it is a case-insensitive directory string. | |

The source of the schema element (for example, the name of the project). | |

The definition of the object class | |

A brief description of the object class. | |

The | |

With | |

With |

Creating and managing a Docker container for 389 Directory Server #Edit source

Note

This section is OPTIONAL; refer to it if you use a 389 Directory Server instance as a Docker container. For regular usage of a 389 Directory Server instance, refer to the rest of the sections.

To create and manage a 389 Directory Server instance as a Docker container, refer to the following examples:

- Pull the latest 389 Directory Server image

To pull the latest 389 Directory Server image from the container registry, run the following command:

>docker pull 389ds/dirsrv:latest- Create a new volume

To create a new volume for the container, run the following example command:

>docker volume create VOLUME- Create a container with basic configuration

To create a container with basic configuration, run the following example command:

>docker create \ -u USERNAME \ -e SUFFIX_NAME="dc=example,dc=com" \ -e DS_DM_PASSWORD=PASSWORD \ -m 1024M \ -p 3389:3389 -p 3636:3636 \ -v VOLUME:/data \ --name INSTANCE \ 389ds/dirsrv:latest- Start the Docker container for 389 Directory Server

To start the Docker container, run the following example command:

>docker start INSTANCE- Execute a command within a running 389 Directory Server container

Assuming that the primary process of the container (

PID 1) is running, you can run a command within a running 389 Directory Server container by using the following syntax:>sudodocker exec -u USERNAME -i -t INSTANCE COMMANDNote: The COMMAND must be executable

To run a chained command or a command enclosed within quotations, you should first run a shell session in the container. For example, you can run commands in the

shshell attached to the container:>sudodocker exec -u USERNAME -i -t INSTANCE sh -c "COMMAND"- Stop the Docker container for 389 Directory Server

To stop the running Docker container, run the following example command:

>docker stop INSTANCE- Remove the Docker container for 389 Directory Server

To remove the Docker container, run the following example command:

>docker rm INSTANCE

Installing 389 Directory Server #Edit source

Install 389 Directory Server with the following command:

>sudozypper install 389-ds

After installation, set up the server as described in Section 5.3.1, “Setting up a new 389 Directory Server instance”.

5.3.1 Setting up a new 389 Directory Server instance #Edit source

You will use the dscreate command to create new 389 Directory Server

instances, and the dsctl command to cleanly remove them.

There are two ways to configure and create a new instance: from a custom configuration file, and from an auto-generated template file. You can use the auto-generated template without changes for a test instance, though for a production system you must carefully review it and make any necessary changes.

Then you will set up administration credentials, manage users and groups, and configure identity services.

The 389 Directory Server is controlled by three primary commands:

dsctlManages a local instance and requires

rootpermissions. Requires you to be connected to a terminal which is running the directory server instance. Used for starting, stopping, backing up the database, and more.dsconfThe primary tool used for administration and configuration of the server. Manages an instance's configuration via its external interfaces. This allows you to make configuration changes remotely on the instance.

dsidmUsed for identity management (managing users, groups, passwords, etc.). The permissions are granted by access controls, so, for example, users can reset their own password or change details of their own account.

Follow these steps to set up a simple instance for testing and development, populated with a small set of sample entries.

5.3.2 Creating a 389 Directory Server instance with a custom configuration file #Edit source

You can create a new 389 Directory Server instance from a simple custom configuration file. This file must be in the INF format, and you can name it anything you like.

The default instance name is localhost. The instance name

cannot be changed after it has been created. It is better to create your own

instance name, rather than using the default, to avoid confusion and to

enable a better understanding of how it all works. The following examples

use the LDAP1 instance name, and a suffix of

dc=LDAP1,dc=COM.

Example 5.2 shows an example configuration file that you can use to create a new 389 Directory Server instance. You can copy and use this file without changes.

Copy the following example file,

LDAP1.inf, to your home directory:Example 5.2: Minimal 389 Directory Server instance configuration file #

# LDAP1.inf [general] config_version = 2 1 [slapd] root_password = PASSWORD2 self_sign_cert = True 3 instance_name = LDAP1 [backend-userroot] sample_entries = yes 4 suffix = dc=LDAP1,dc=COM

This line is required, indicating that this is a version 2 setup INF file.

Create a strong

root_passwordfor the ldap usercn=Directory Manager. This user is for connecting (binding) to the directory.Create self-signed server certificates in

/etc/dirsrv/slapd-LDAP1.Populate the new instance with sample user and group entries.

To create the 389 Directory Server instance from Example 5.2, run the following command:

>sudodscreate -v from-file LDAP1.inf |\tee LDAP1-OUTPUT.txtThis shows all activity during the instance creation, stores all the messages in

LDAP1-OUTPUT.txt, and creates a working LDAP server in about a minute. The verbose output contains a lot of useful information. If you do not want to save it, then delete the| tee LDAP1-OUTPUT.txtportion of the command.If the

dscreatecommand should fail, the messages will tell you why. After correcting any issues, remove the instance (see Step 5) and create a new instance.A successful installation reports

Completed installation for LDAP1. Check the status of your new server:>sudodsctl LDAP1 statusInstance "LDAP1" is runningThe following commands are for cleanly removing the instance. The first command performs a dry run and does not remove the instance. When you are sure you want to remove it, use the second command with the

--do-itoption:>sudodsctl LDAP1 removeNot removing: if you are sure, add --do-it>sudodsctlLDAP1 remove --do-itThis command also removes partially installed or corrupted instances. You can reliably create and remove instances as often as you want.

If you forget the name of your instance, use dsctl to

list all instances:

>sudo dsctl -lslapd-LDAP1

5.3.3 Creating a 389 Directory Server instance from a template #Edit source

You can auto-create a template for a new 389 Directory Server instance with the

dscreate command. This creates a template that you can

use without making any changes, for testing. For production systems, review

and change it to suit your own requirements. The defaults are

documented in the template file, and commented out. To make changes,

uncomment the default and enter your own value. All options are well

documented.

The following example prints the template to stdout:

>sudo dscreate create-template

This is good for a quick review of the template, but you must create a file to use in creating your new 389 Directory Server instance. You can name this file anything you want:

>sudo dscreate create-template TEMPLATE.txt

This is a snippet from the new file: