17 Common Problems and Their Solutions

This chapter describes a range of potential problems and their solutions. Even if your situation is not precisely listed here, there may be one similar enough to offer hints to the solution of your problem.

17.1 Finding and Gathering Information #

Linux reports things in a very detailed way. There are several places to look when you encounter problems with your system, most of which are standard to Linux systems in general, and some are relevant to openSUSE Leap systems. Most log files can be viewed with YaST ( › ).

YaST offers the possibility to collect all system information needed by the support team. Use › and select the problem category. When all information is gathered, attach it to your support request.

A list of the most frequently checked log files follows with the description

of their typical purpose. Paths containing ~ refer to

the current user's home directory.

Table 17.1: Log Files #

|

Log File |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Messages from the desktop applications currently running. |

|

|

Log files from AppArmor, see Book “Security Guide” for detailed information. |

|

|

Log file from Audit to track any access to files, directories, or resources of your system, and trace system calls. See Book “Security Guide” for detailed information. |

|

|

Messages from the mail system. |

|

|

Log file from NetworkManager to collect problems with network connectivity |

|

|

Directory containing Samba server and client log messages. |

|

|

All messages from the kernel and system log daemon with the “warning” level or higher. |

|

|

Binary file containing user login records for the current machine

session. View it with |

|

|

Various start-up and runtime log files from the X Window System. It is useful for debugging failed X start-ups. |

|

|

Directory containing YaST's actions and their results. |

|

|

Log file of Zypper. |

Apart from log files, your machine also supplies you with information about

the running system. See

Table 17.2: System Information With the /proc File System

Table 17.2: System Information With the /proc File System #

|

File |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Contains processor information, including its type, make, model, and performance. |

|

|

Shows which DMA channels are currently being used. |

|

|

Shows which interrupts are in use, and how many of each have been in use. |

|

|

Displays the status of I/O (input/output) memory. |

|

|

Shows which I/O ports are in use at the moment. |

|

|

Displays memory status. |

|

|

Displays the individual modules. |

|

|

Displays devices currently mounted. |

|

|

Shows the partitioning of all hard disks. |

|

|

Displays the current version of Linux. |

Apart from the /proc file system, the Linux kernel

exports information with the sysfs module, an in-memory

file system. This module represents kernel objects, their attributes and

relationships. For more information about sysfs, see the

context of udev in Book “Reference”, Chapter 16 “Dynamic Kernel Device Management with udev”.

Table 17.3 contains

an overview of the most common directories under /sys.

Table 17.3: System Information With the /sys File System #

|

File |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Contains subdirectories for each block device discovered in the system. Generally, these are mostly disk type devices. |

|

|

Contains subdirectories for each physical bus type. |

|

|

Contains subdirectories grouped together as a functional types of devices (like graphics, net, printer, etc.) |

|

|

Contains the global device hierarchy. |

Linux comes with several tools for system analysis and monitoring. See Book “System Analysis and Tuning Guide”, Chapter 2 “System Monitoring Utilities” for a selection of the most important ones used in system diagnostics.

Each of the following scenarios begins with a header describing the problem followed by a paragraph or two offering suggested solutions, available references for more detailed solutions, and cross-references to other scenarios that are related.

17.2 Boot Problems #

Boot problems are situations when your system does not boot properly (does not boot to the expected target and login screen).

17.2.1 The GRUB 2 Boot Loader Fails to Load #

If the hardware is functioning properly, it is possible that the boot loader is corrupted and Linux cannot start on the machine. In this case, it is necessary to repair the boot loader. To do so, you need to start the Rescue System as described in Section 17.5.2, “Using the Rescue System” and follow the instructions in Section 17.5.2.4, “Modifying and Re-installing the Boot Loader”.

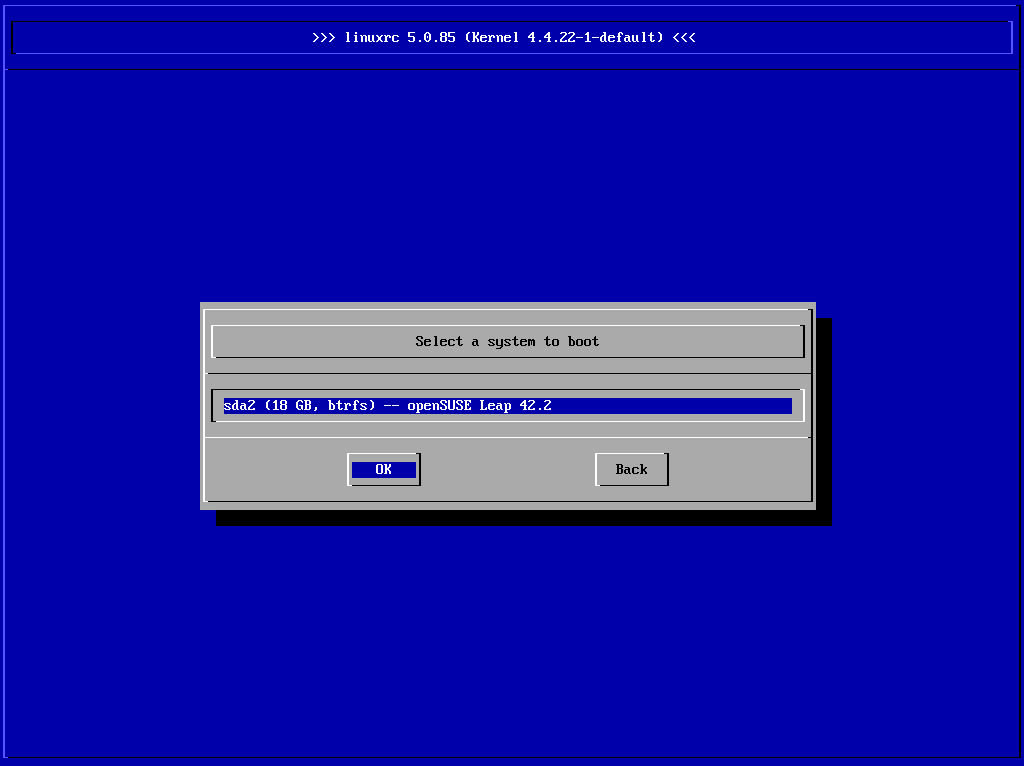

Alternatively, you can use the Rescue System to fix the boot loader as follows. Boot your machine from the installation media. In the boot screen, choose › . Select the disk containing the installed system and kernel with the default kernel options.

Figure 17.1: Select Disk #

When the system is booted, start YaST and switch to › . Make sure that the option is enabled, and click . This fixes the corrupted boot loader by overwriting it, or installs the boot loader if it is missing.

Other reasons for the machine not booting may be BIOS-related:

- BIOS Settings

Check your BIOS for references to your hard disk. GRUB 2 may simply not be started if the hard disk itself cannot be found with the current BIOS settings.

- BIOS Boot Order

Check whether your system's boot order includes the hard disk. If the hard disk option was not enabled, your system may install properly, but fails to boot when access to the hard disk is required.

17.2.2 No Login or Prompt Appears #

This behavior typically occurs after a failed kernel upgrade and it is known as a kernel panic because of the type of error on the system console that sometimes can be seen at the final stage of the process. If, in fact, the machine has just been rebooted following a software update, the immediate goal is to reboot it using the old, proven version of the Linux kernel and associated files. This can be done in the GRUB 2 boot loader screen during the boot process as follows:

Reboot the computer using the reset button, or switch it off and on again.

When the GRUB 2 boot screen becomes visible, select the entry and choose the previous kernel from the menu. The machine will boot using the prior version of the kernel and its associated files.

After the boot process has completed, remove the newly installed kernel and, if necessary, set the default boot entry to the old kernel using the YaST module. For more information refer to Book “Reference”, Chapter 12 “The Boot Loader GRUB 2”, Section 12.3 “Configuring the Boot Loader with YaST”. However, doing this is probably not necessary because automated update tools normally modify it for you during the rollback process.

Reboot.

If this does not fix the problem, boot the computer using the installation media. After the machine has booted, continue with Step 3.

17.2.3 No Graphical Login #

If the machine starts, but does not boot into the graphical login

manager, anticipate problems either with the choice of the default systemd

target or the configuration of the X Window System. To check the current

systemd default target run the command sudo systemctl

get-default. If the value returned is not

graphical.target, run the command sudo

systemctl isolate graphical.target. If the graphical login screen

starts, log in and start › ›

and set the to . From now on the system should boot into the graphical

login screen.

If the graphical login screen does not start even if having booted or

switched to the graphical target, your desktop or X Window software is

probably misconfigured or corrupted. Examine the log files at

/var/log/Xorg.*.log for detailed messages from the X

server as it attempted to start. If the desktop fails during start, it may

log error messages to the system journal that can be queried with the

command journalctl (see Book “Reference”, Chapter 11 “journalctl: Query the systemd Journal”

for more information). If these error messages hint at a configuration

problem in the X server, try to fix these issues. If the graphical system

still does not come up, consider reinstalling the graphical desktop.

17.2.4 Root Btrfs Partition Cannot Be Mounted #

If a btrfs root partition

becomes corrupted, try the following options:

Mount the partition with the

-o recoveryoption.If that fails, run

btrfs-zero-logon your root partition.

17.2.5 Force Checking Root Partitions #

If the root partition becomes corrupted, use the parameter

forcefsck on the boot prompt. This passes the option

-f (force) to the fsck command.

17.3 Login Problems #

Login problems occur when your machine does boot to the expected welcome screen or login prompt, but refuses to accept the user name and password, or accepts them but then does not behave properly (fails to start the graphic desktop, produces errors, drops to a command line, etc.).

17.3.1 Valid User Name and Password Combinations Fail #

This usually occurs when the system is configured to use network

authentication or directory services and, for some reason, cannot retrieve

results from its configured servers. The

root user, as the only local

user, is the only user that can still log in to these machines. The

following are some common reasons a machine appears functional but cannot

process logins correctly:

The network is not working. For further directions on this, turn to Section 17.4, “Network Problems”.

DNS is not working at the moment (which prevents GNOME from working and the system from making validated requests to secure servers). One indication that this is the case is that the machine takes an extremely long time to respond to any action. Find more information about this topic in Section 17.4, “Network Problems”.

If the system is configured to use Kerberos, the system's local time may have drifted past the accepted variance with the Kerberos server time (this is typically 300 seconds). If NTP (network time protocol) is not working properly or local NTP servers are not working, Kerberos authentication ceases to function because it depends on common clock synchronization across the network.

The system's authentication configuration is misconfigured. Check the PAM configuration files involved for any typographical errors or misordering of directives. For additional background information about PAM and the syntax of the configuration files involved, refer to Book “Security Guide”, Chapter 2 “Authentication with PAM”.

The home partition is encrypted. Find more information about this topic in Section 17.3.3, “Login to Encrypted Home Partition Fails”.

In all cases that do not involve external network problems, the solution is to reboot the system into single-user mode and repair the configuration before booting again into operating mode and attempting to log in again. To boot into single-user mode:

Reboot the system. The boot screen appears, offering a prompt.

Press Esc to exit the splash screen and get to the GRUB 2 text-based menu.

Press B to enter the GRUB 2 editor.

Add the following parameter to the line containing the kernel parameters:

systemd.unit=rescue.target

Press F10.

Enter the user name and password for

root.Make all the necessary changes.

Boot into the full multiuser and network mode by entering

systemctl isolate graphical.targetat the command line.

17.3.2 Valid User Name and Password Not Accepted #

This is by far the most common problem users encounter, because there are many reasons this can occur. Depending on whether you use local user management and authentication or network authentication, login failures occur for different reasons.

Local user management can fail for the following reasons:

The user may have entered the wrong password.

The user's home directory containing the desktop configuration files is corrupted or write protected.

There may be problems with the X Window System authenticating this particular user, especially if the user's home directory has been used with another Linux distribution prior to installing the current one.

To locate the reason for a local login failure, proceed as follows:

Check whether the user remembered their password correctly before you start debugging the whole authentication mechanism. If the user may have not remember their password correctly, use the YaST User Management module to change the user's password. Pay attention to the Caps Lock key and unlock it, if necessary.

Log in as

rootand check the system journal withjournalctl -efor error messages of the login process and of PAM.Try to log in from a console (using Ctrl–Alt–F1). If this is successful, the blame cannot be put on PAM, because it is possible to authenticate this user on this machine. Try to locate any problems with the X Window System or the GNOME desktop. For more information, refer to Section 17.3.4, “Login Successful but GNOME Desktop Fails”.

If the user's home directory has been used with another Linux distribution, remove the

Xauthorityfile in the user's home. Use a console login via Ctrl–Alt–F1 and runrm .Xauthorityas this user. This should eliminate X authentication problems for this user. Try graphical login again.If the desktop could not start because of corrupt configuration files, proceed with Section 17.3.4, “Login Successful but GNOME Desktop Fails”.

In the following, common reasons a network authentication for a particular user may fail on a specific machine are listed:

The user may have entered the wrong password.

The user name exists in the machine's local authentication files and is also provided by a network authentication system, causing conflicts.

The home directory exists but is corrupt or unavailable. Perhaps it is write protected or is on a server that is inaccessible at the moment.

The user does not have permission to log in to that particular host in the authentication system.

The machine has changed host names, for whatever reason, and the user does not have permission to log in to that host.

The machine cannot reach the authentication server or directory server that contains that user's information.

There may be problems with the X Window System authenticating this particular user, especially if the user's home has been used with another Linux distribution prior to installing the current one.

To locate the cause of the login failures with network authentication, proceed as follows:

Check whether the user remembered their password correctly before you start debugging the whole authentication mechanism.

Determine the directory server which the machine relies on for authentication and make sure that it is up and running and properly communicating with the other machines.

Determine that the user's user name and password work on other machines to make sure that their authentication data exists and is properly distributed.

See if another user can log in to the misbehaving machine. If another user can log in without difficulty or if

rootcan log in, log in and examine the system journal withjournalctl -e> file. Locate the time stamps that correspond to the login attempts and determine if PAM has produced any error messages.Try to log in from a console (using Ctrl–Alt–F1). If this is successful, the problem is not with PAM or the directory server on which the user's home is hosted, because it is possible to authenticate this user on this machine. Try to locate any problems with the X Window System or the GNOME desktop. For more information, refer to Section 17.3.4, “Login Successful but GNOME Desktop Fails”.

If the user's home directory has been used with another Linux distribution, remove the

Xauthorityfile in the user's home. Use a console login via Ctrl–Alt–F1 and runrm .Xauthorityas this user. This should eliminate X authentication problems for this user. Try graphical login again.If the desktop could not start because of corrupt configuration files, proceed with Section 17.3.4, “Login Successful but GNOME Desktop Fails”.

17.3.3 Login to Encrypted Home Partition Fails #

It is recommended to use an encrypted home partition for laptops. If you cannot log in to your laptop, the reason is usually simple: your partition could not be unlocked.

During the boot time, you need to enter the passphrase to unlock your encrypted partition. If you do not enter it, the boot process continues, leaving the partition locked.

To unlock your encrypted partition, proceed as follows:

Switch to the text console with Ctrl–Alt–F1.

Become

root.Restart the unlocking process again with:

root #systemctl restart home.mountEnter your passphrase to unlock your encrypted partition.

Exit the text console and switch back to the login screen with Alt–F7.

Log in as usual.

17.3.4 Login Successful but GNOME Desktop Fails #

If this is the case, it is likely that your GNOME configuration files have become corrupted. Some symptoms may include the keyboard failing to work, the screen geometry becoming distorted, or even the screen coming up as a bare gray field. The important distinction is that if another user logs in, the machine works normally. It is then likely that the problem can be fixed relatively quickly by simply moving the user's GNOME configuration directory to a new location, which causes GNOME to initialize a new one. Although the user is forced to reconfigure GNOME, no data is lost.

Switch to a text console by pressing Ctrl–Alt–F1.

Log in with your user name.

Move the user's GNOME configuration directories to a temporary location:

tux >mv .gconf .gconf-ORIG-RECOVERtux >mv .gnome2 .gnome2-ORIG-RECOVERLog out.

Log in again, but do not run any applications.

Recover your individual application configuration data (including the Evolution e-mail client data) by copying the

~/.gconf-ORIG-RECOVER/apps/directory back into the new~/.gconfdirectory as follows:tux >cp -a .gconf-ORIG-RECOVER/apps .gconf/If this causes the login problems, attempt to recover only the critical application data and reconfigure the remainder of the applications.

17.4 Network Problems #

Many problems of your system may be network-related, even though they do not seem to be at first. For example, the reason for a system not allowing users to log in may be a network problem of some kind. This section introduces a simple checklist you can apply to identify the cause of any network problem encountered.

Procedure 17.1: How to Identify Network Problems #

When checking the network connection of your machine, proceed as follows:

If you use an Ethernet connection, check the hardware first. Make sure that your network cable is properly plugged into your computer and router (or hub, etc.). The control lights next to your Ethernet connector are normally both be active.

If the connection fails, check whether your network cable works with another machine. If it does, your network card causes the failure. If hubs or switches are included in your network setup, they may be faulty, as well.

If using a wireless connection, check whether the wireless link can be established by other machines. If not, contact the wireless network's administrator.

When you have checked your basic network connectivity, try to find out which service is not responding. Gather the address information of all network servers needed in your setup. Either look them up in the appropriate YaST module or ask your system administrator. The following list gives some typical network servers involved in a setup together with the symptoms of an outage.

- DNS (Name Service)

A broken or malfunctioning name service affects the network's functionality in many ways. If the local machine relies on any network servers for authentication and these servers cannot be found because of name resolution issues, users would not even be able to log in. Machines in the network managed by a broken name server would not be able to “see” each other and communicate.

- NTP (Time Service)

A malfunctioning or completely broken NTP service could affect Kerberos authentication and X server functionality.

- NFS (File Service)

If any application needs data stored in an NFS mounted directory, it cannot start or function properly if this service was down or misconfigured. In the worst case scenario, a user's personal desktop configuration would not come up if their home directory containing the

.gconfsubdirectory could not be found because of a faulty NFS server.- Samba (File Service)

If any application needs data stored in a directory on a faulty Samba server, it cannot start or function properly.

- NIS (User Management)

If your openSUSE Leap system relies on a faulty NIS server to provide the user data, users cannot log in to this machine.

- LDAP (User Management)

If your openSUSE Leap system relies on a faulty LDAP server to provide the user data, users cannot log in to this machine.

- Kerberos (Authentication)

Authentication will not work and login to any machine fails.

- CUPS (Network Printing)

Users cannot print.

Check whether the network servers are running and whether your network setup allows you to establish a connection:

Important: Limitations

The debugging procedure described below only applies to a simple network server/client setup that does not involve any internal routing. It assumes both server and client are members of the same subnet without the need for additional routing.

Use

pingIP_ADDRESS/HOSTNAME (replace with the host name or IP address of the server) to check whether each one of them is up and responding to the network. If this command is successful, it tells you that the host you were looking for is up and running and that the name service for your network is configured correctly.If ping fails with

destination host unreachable, either your system or the desired server is not properly configured or down. Check whether your system is reachable by runningpingIP address or YOUR_HOSTNAME from another machine. If you can reach your machine from another machine, it is the server that is not running or not configured correctly.If ping fails with

unknown host, the name service is not configured correctly or the host name used was incorrect. For further checks on this matter, refer to Step 4.b. If ping still fails, either your network card is not configured correctly or your network hardware is faulty.Use

hostHOSTNAME to check whether the host name of the server you are trying to connect to is properly translated into an IP address and vice versa. If this command returns the IP address of this host, the name service is up and running. If thehostcommand fails, check all network configuration files relating to name and address resolution on your host:/etc/resolv.confThis file is used to keep track of the name server and domain you are currently using. It can be modified manually or automatically adjusted by YaST or DHCP. Automatic adjustment is preferable. However, make sure that this file has the following structure and all network addresses and domain names are correct:

search FULLY_QUALIFIED_DOMAIN_NAME nameserver IPADDRESS_OF_NAMESERVER

This file can contain more than one name server address, but at least one of them must be correct to provide name resolution to your host. If needed, adjust this file using the YaST Network Settings module (Hostname/DNS tab).

If your network connection is handled via DHCP, enable DHCP to change host name and name service information by selecting (can be set globally for any interface or per interface) and in the YaST Network Settings module (Hostname/DNS tab).

/etc/nsswitch.confThis file tells Linux where to look for name service information. It should look like this:

... hosts: files dns networks: files dns ...

The

dnsentry is vital. It tells Linux to use an external name server. Normally, these entries are automatically managed by YaST, but it would be prudent to check.If all the relevant entries on the host are correct, let your system administrator check the DNS server configuration for the correct zone information. For detailed information about DNS, refer to Book “Reference”, Chapter 19 “The Domain Name System”. If you have made sure that the DNS configuration of your host and the DNS server are correct, proceed with checking the configuration of your network and network device.

If your system cannot establish a connection to a network server and you have excluded name service problems from the list of possible culprits, check the configuration of your network card.

Use the command

ip addr showNETWORK_DEVICE to check whether this device was properly configured. Make sure that theinet addresswith the netmask (/MASK) is configured correctly. An error in the IP address or a missing bit in your network mask would render your network configuration unusable. If necessary, perform this check on the server as well.If the name service and network hardware are properly configured and running, but some external network connections still get long time-outs or fail entirely, use

tracerouteFULLY_QUALIFIED_DOMAIN_NAME (executed asroot) to track the network route these requests are taking. This command lists any gateway (hop) that a request from your machine passes on its way to its destination. It lists the response time of each hop and whether this hop is reachable. Use a combination of traceroute and ping to track down the culprit and let the administrators know.

When you have identified the cause of your network trouble, you can resolve it yourself (if the problem is located on your machine) or let the system administrators of your network know about your findings so they can reconfigure the services or repair the necessary systems.

17.4.1 NetworkManager Problems #

If you have a problem with network connectivity, narrow it down as described in Procedure 17.1, “How to Identify Network Problems”. If NetworkManager seems to be the culprit, proceed as follows to get logs providing hints on why NetworkManager fails:

Open a shell and log in as

root.Restart the NetworkManager:

tux >sudosystemctl restart NetworkManagerOpen a Web page, for example, http://www.opensuse.org as normal user to see, if you can connect.

Collect any information about the state of NetworkManager in

/var/log/NetworkManager.

For more information about NetworkManager, refer to Book “Reference”, Chapter 28 “Using NetworkManager”.

17.5 Data Problems #

Data problems are when the machine may or may not boot properly but, in either case, it is clear that there is data corruption on the system and that the system needs to be recovered. These situations call for a backup of your critical data, enabling you to recover the system state from before your system failed.

17.5.1 Managing Partition Images #

Sometimes you need to perform a backup from an entire partition or even

hard disk. Linux comes with the dd tool which can create

an exact copy of your disk. Combined with gzip you save

some space.

Procedure 17.2: Backing up and Restoring Hard Disks #

Start a Shell as user

root.Select your source device. Typically this is something like

/dev/sda(labeled as SOURCE).Decide where you want to store your image (labeled as BACKUP_PATH). It must be different from your source device. In other words: if you make a backup from

/dev/sda, your image file must not to be stored under/dev/sda.Run the commands to create a compressed image file:

root #dd if=/dev/SOURCE | gzip > /BACKUP_PATH/image.gzRestore the hard disk with the following commands:

root #gzip -dc /BACKUP_PATH/image.gz | dd of=/dev/SOURCE

If you only need to back up a partition, replace the SOURCE placeholder with your respective partition. In this case, your image file can lie on the same hard disk, but on a different partition.

17.5.2 Using the Rescue System #

There are several reasons a system could fail to come up and run properly. A corrupted file system following a system crash, corrupted configuration files, or a corrupted boot loader configuration are the most common ones.

To help you to resolve these situations, openSUSE Leap contains a rescue system that you can boot. The rescue system is a small Linux system that can be loaded into a RAM disk and mounted as root file system, allowing you to access your Linux partitions from the outside. Using the rescue system, you can recover or modify any important aspect of your system.

Manipulate any type of configuration file.

Check the file system for defects and start automatic repair processes.

Access the installed system in a “change root” environment.

Check, modify, and re-install the boot loader configuration.

Recover from a badly installed device driver or unusable kernel.

Resize partitions using the parted command. Find more information about this tool at the GNU Parted Web site http://www.gnu.org/software/parted/parted.html.

The rescue system can be loaded from various sources and locations. The simplest option is to boot the rescue system from the original installation medium.

Insert the installation medium into your DVD drive.

Reboot the system.

At the boot screen, press F4 and choose . Then choose from the main menu.

Enter

rootat theRescue:prompt. A password is not required.

If your hardware setup does not include a DVD drive, you can boot the rescue

system from a network source. The following example applies to a remote boot

scenario—if using another boot medium, such as a DVD, modify the

info file accordingly and boot as you would for a

normal installation.

Enter the configuration of your PXE boot setup and add the lines

install=PROTOCOL://INSTSOURCEandrescue=1. If you need to start the repair system, userepair=1instead. As with a normal installation, PROTOCOL stands for any of the supported network protocols (NFS, HTTP, FTP, etc.) and INSTSOURCE for the path to your network installation source.Boot the system using “Wake on LAN”.

Enter

rootat theRescue:prompt. A password is not required.

When you have entered the rescue system, you can use the virtual consoles that can be reached with Alt–F1 to Alt–F6.

A shell and other useful utilities, such as the mount program, are

available in the /bin directory. The

/sbin directory contains important file and network

utilities for reviewing and repairing the file system. This directory also

contains the most important binaries for system maintenance, such as

fdisk, mkfs, mkswap,

mount, and shutdown,

ip and ss for maintaining the network.

The directory /usr/bin contains the vi editor, find,

less, and SSH.

To see the system messages, either use the command dmesg

or view the system log with journalctl.

17.5.2.1 Checking and Manipulating Configuration Files #

As an example for a configuration that might be fixed using the rescue system, imagine you have a broken configuration file that prevents the system from booting properly. You can fix this using the rescue system.

To manipulate a configuration file, proceed as follows:

Start the rescue system using one of the methods described above.

To mount a root file system located under

/dev/sda6to the rescue system, use the following command:tux >sudomount /dev/sda6 /mntAll directories of the system are now located under

/mntChange the directory to the mounted root file system:

tux >sudocd /mntOpen the problematic configuration file in the vi editor. Adjust and save the configuration.

Unmount the root file system from the rescue system:

tux >sudoumount /mntReboot the machine.

17.5.2.2 Repairing and Checking File Systems #

Generally, file systems cannot be repaired on a running system. If you

encounter serious problems, you may not even be able to mount your root file

system and the system boot may end with a “kernel panic”. In

this case, the only way is to repair the system from the outside. The system

contains the utilities to check and repair the btrfs,

ext2, ext3, ext4,

xfs, dosfs, and vfat

file systems. Look for the command

fsck.FILESYSTEM.

For example, if you need a file system

check for btrfs, use fsck.btrfs.

17.5.2.3 Accessing the Installed System #

If you need to access the installed system from the rescue system, you need to do this in a change root environment. For example, to modify the boot loader configuration, or to execute a hardware configuration utility.

To set up a change root environment based on the installed system, proceed as follows:

Tip: Import LVM Volume Groups

If you are using an LVM setup (refer to Book “Reference”, Chapter 5 “Expert Partitioner”, Section 5.2 “LVM Configuration” for more general details), import all existing volume groups to be able to find and mount the device(s):

rootvgimport -aRun

lsblkto check which node corresponds to the root partition. It is/dev/sda2in our example:tux >lsblk NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINT sda 8:0 0 149,1G 0 disk ├─sda1 8:1 0 2G 0 part [SWAP] ├─sda2 8:2 0 20G 0 part / └─sda3 8:3 0 127G 0 part └─cr_home 254:0 0 127G 0 crypt /homeMount the root partition from the installed system:

tux >sudomount /dev/sda2 /mntMount

/proc,/dev, and/syspartitions:tux >sudomount -t proc none /mnt/proctux >sudomount --rbind /dev /mnt/devtux >sudomount --rbind /sys /mnt/sysNow you can “change root” into the new environment, keeping the

bashshell:tux >chroot /mnt /bin/bashFinally, mount the remaining partitions from the installed system:

tux >mount -aNow you have access to the installed system. Before rebooting the system, unmount the partitions with

umount-aand leave the “change root” environment withexit.

Warning: Limitations

Although you have full access to the files and applications of the

installed system, there are some limitations. The kernel that is running is

the one that was booted with the rescue system, not with the change root

environment. It only supports essential hardware and it is not possible to

add kernel modules from the installed system unless the kernel versions are

identical. Always check the version of the currently running (rescue)

kernel with uname -r and then find out if a matching

subdirectory exists in the /lib/modules directory in

the change root environment. If yes, you can use the installed modules,

otherwise you need to supply their correct versions on other media, such as

a flash disk. Most often the rescue kernel version differs from the

installed one — then you cannot simply access a sound card, for

example. It is also not possible to start a graphical user interface.

Also note that you leave the “change root” environment when you switch the console with Alt–F1 to Alt–F6.

17.5.2.4 Modifying and Re-installing the Boot Loader #

Sometimes a system cannot boot because the boot loader configuration is corrupted. The start-up routines cannot, for example, translate physical drives to the actual locations in the Linux file system without a working boot loader.

To check the boot loader configuration and re-install the boot loader, proceed as follows:

Perform the necessary steps to access the installed system as described in Section 17.5.2.3, “Accessing the Installed System”.

Check that the GRUB 2 boot loader is installed on the system. If not, install the package

grub2and runtux >sudogrub2-install /dev/sdaCheck whether the following files are correctly configured according to the GRUB 2 configuration principles outlined in Book “Reference”, Chapter 12 “The Boot Loader GRUB 2” and apply fixes if necessary.

/etc/default/grub/boot/grub2/device.map(optional file, only present if created manually)/boot/grub2/grub.cfg(this file is generated, do not edit)/etc/sysconfig/bootloader

Re-install the boot loader using the following command sequence:

tux >sudogrub2-mkconfig -o /boot/grub2/grub.cfgUnmount the partitions, log out from the “change root” environment, and reboot the system:

tux >umount -a exit reboot

17.5.2.5 Fixing Kernel Installation #

A kernel update may introduce a new bug which can impact the operation of your system. For example a driver for a piece of hardware in your system may be faulty, which prevents you from accessing and using it. In this case, revert to the last working kernel (if available on the system) or install the original kernel from the installation media.

Tip: How to Keep Last Kernels after Update

To prevent failures to boot after a faulty kernel update, use the kernel

multiversion feature and tell libzypp which

kernels you want to keep after the update.

For example to always keep the last two kernels and the currently running one, add

multiversion.kernels = latest,latest-1,running

to the /etc/zypp/zypp.conf file. See

Book “Reference”, Chapter 6 “Installing Multiple Kernel Versions” for more information.

A similar case is when you need to re-install or update a broken driver for a device not supported by openSUSE Leap. For example when a hardware vendor uses a specific device, such as a hardware RAID controller, which needs a binary driver to be recognized by the operating system. The vendor typically releases a Driver Update Disk (DUD) with the fixed or updated version of the required driver.

In both cases you need to access the installed system in the rescue mode and fix the kernel related problem, otherwise the system may fail to boot correctly:

Boot from the openSUSE Leap installation media.

If you are recovering after a faulty kernel update, skip this step. If you need to use a driver update disk (DUD), press F6 to load the driver update after the boot menu appears, and choose the path or URL to the driver update and confirm with .

Choose from the boot menu and press Enter. If you chose to use DUD, you will be asked to specify where the driver update is stored.

Enter

rootat theRescue:prompt. A password is not required.Manually mount the target system and “change root” into the new environment. For more information, see Section 17.5.2.3, “Accessing the Installed System”.

If using DUD, install/re-install/update the faulty device driver package. Always make sure the installed kernel version exactly matches the version of the driver you are installing.

If fixing faulty kernel update installation, you can install the original kernel from the installation media with the following procedure.

Identify your DVD device with

hwinfo --cdromand mount it withmount /dev/sr0 /mnt.Navigate to the directory where your kernel files are stored on the DVD, for example

cd /mnt/suse/x86_64/.Install required

kernel-*,kernel-*-base, andkernel-*-extrapackages of your flavor with therpm -icommand.

Update configuration files and reinitialize the boot loader if needed. For more information, see Section 17.5.2.4, “Modifying and Re-installing the Boot Loader”.

Remove any bootable media from the system drive and reboot.